|

|

This mansion at 4938 Drexel Boulevard

was built in 1890 for physician John A. McGill. The building,

notes Julius Lewis, is “one of Cobb’s biggest, if

not most successful, houses. The gray stone, French Renaissance

design echoes the University of Chicago buildings” a

few blocks to the south. The architectural references to a

castle may, Lewis speculates, be a result of the owner’s

wishes.

|

Beginning his career at a time when there were probably no more

than 30 U.S. architects who had received any formal training—either

in the U.S. or abroad—Cobb was an obvious choice for clients

seeking architects with an understanding of historicism, the borrowing

and transforming of previous architectural idioms.

Although Cobb worked in the midst of an architectural revolution,

his own contributions were more stylistic than structural. And his

best work, says Lewis, came not in the the University of Chicago’s

Oxford–inspired quadrangles. Designing buildings to meet “a

demand for Gothic,” Lewis notes, “his campus buildings

are about as Gothic as the Reliance Building,” a Loop monument

to modernity. He pauses, reconsiders: “Still, the buildings

are gray, and they do have gargoyles and grotesques.”

|

Cobb’s fondness for ornamentation

rooted in classical mythology is evident in this detail from

a pillar at Yerkes Observatory. Each pillar consists of three

stacked sets of the same designs—incorporating real and

imaginary animals, signs of the zodiac, phases of the moon,

and a caricature of the University’s first president,

William Rainey Harper.

|

Cobb’s best work, Lewis continues, was done in Chicago and

in the Romanesque revival idiom first made famous by H. H. Richardson.

Used for residences, clubs, and commercial buildings well into the

1890s, Richardsonian Romanesque buildings often featured heavy,

rough-cut stone walls, rounded arches and squat columns, deeply

recessed windows, and pressed metal bays and turrets. With a natural

talent for ornamental drawing, Cobb delighted in adding fancifully

elaborate detail—whether the aquatic figures decorating his

Fisheries Building for the Columbian Exposition, the playful grotesques

on the Chicago quadrangles, or the celestial imagery at Yerkes Observatory

in Williams Bay, Wisconsin.

In 1898, Cobb left Chicago for Washington, D.C. (though he maintained

an office in Chicago for several years after the move). With his

national reputation—he had won commissions for banks, residences,

and office buildings all over the country—he may have gone

east for his children’s health. But it’s also likely,

says Lewis, that he was “chasing important work in Washington,”

especially in light of a construction slump that hit Chicago following

the panic of 1893.

In fact, after 1898, when the bulk of his work for the University

was done, Cobb designed only two buildings of importance in Chicago—the

Dutch Renaissance–inspired warehouse and office building at

Dearborn and Kinzie that now houses Harry Caray’s Restaurant,

and the Chicago Post Office and Federal Building. “The old

Post Office” occupied an entire block (between Dearborn and

Clark Streets and Adams and Jackson Streets) until 1965, when it

was torn down and replaced by a federal complex.

Once in Washington, the work Cobb sought—a chance to repeat

his U of C experience by creating a campus for the new American

University—never materialized. Asked to design only one building

for the new university, he soon moved on to New York City. There

his work included both office buildings and residences. He was active

as an architect until his death in 1931. Lewis says he and Daniel

are “hot on the trail” of several of Cobb’s New York

houses, but the record is sparse, partly because he was no longer

getting the day’s biggest commissions. “After he left

Chicago, Cobb declined,” Lewis says, “both in terms of

popularity and in the quality of his work.”

Perhaps the most important reason for Cobb’s decline, explains

Lewis, was that, as architectural styles changed, he began “to

be perceived as old-fashioned. After the Columbian Exposition in

the Midwest, and even before in the East, there was a great hunger

for Beaux Arts buildings,” with restrained, classical lines.

“Not very comfortable with the classical idiom,” Cobb

began to lose business to firms like McKim, Mead & White. McKim’s

Agricultural Building had been among the most influential structures

at the 1893 Exposition—far outshining Cobb’s seven buildings

there—and he designed such Manhattan landmarks as the Pennsylvania

Railroad Station and the J. Pierpont Morgan Library.

|

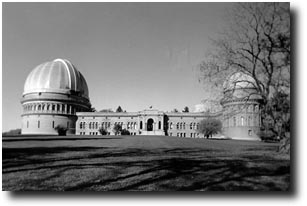

In designing the Yerkes Observatory

in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, Cobb created a relatively inexpensive

and largely functional building to accommodate the observatory’s

three telescopes (including the beautiful curved-wood interior

of the largest dome). But the architect’s love of fanciful

detail, says Lewis, can be seen “in a riot of ornament

at the entrances and around the cornices.”

|

Nor was Cobb a builder of skyscrapers. Instead, his version of

Sullivan’s “form follows function” dictum was seen

most clearly in his design for Yerkes Observatory, completed in

1897. The building, which needed to house a 40-inch telescope and

two smaller telescopes, posed, in Lewis’s words, “a problem

for which no historical solution existed.” Cobb solved the

problem by creating an extremely functional building. One dome,

with a still stunning interior of curved wood, houses the largest

telescope, appropriately dominating the design. The two smaller

domes at the observatory’s other end provide an architectural

balancing act. At the same time, the structure, with its repeated

patterns of arcades and pillars, easily fits into the Romanesque

style. In the end, the Yerkes Observatory is one of Cobb’s

most Richardsonian designs, showing the same ability to incorporate

decoration without detracting from the structure’s larger lines

and function.

Although Henry Ives Cobb was no Henry Hobson Richardson, Julius

Lewis still believes that the architect deserves a book of his own:

“A better understanding of Cobb’s work is important for

a picture of that time. The modernist strain still trumpeted today

was only one kind of architecture at that time—perhaps the

least of it.”

|