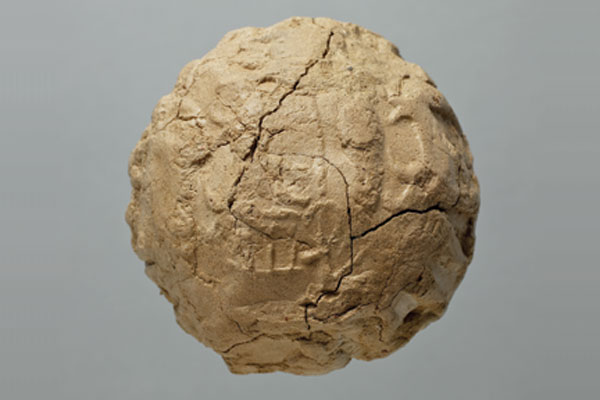

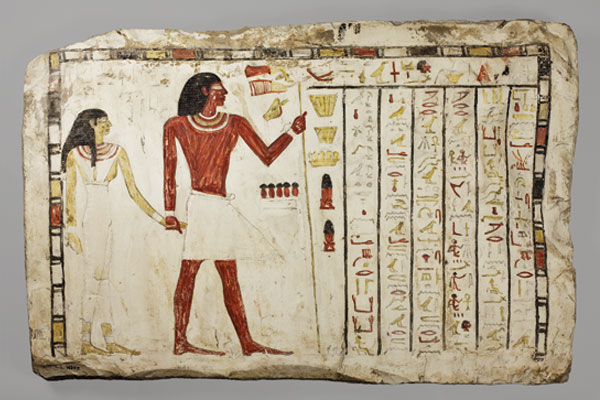

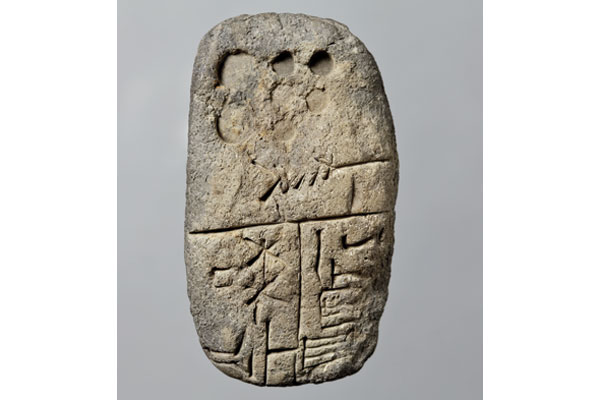

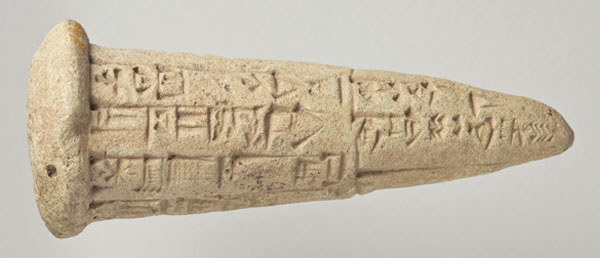

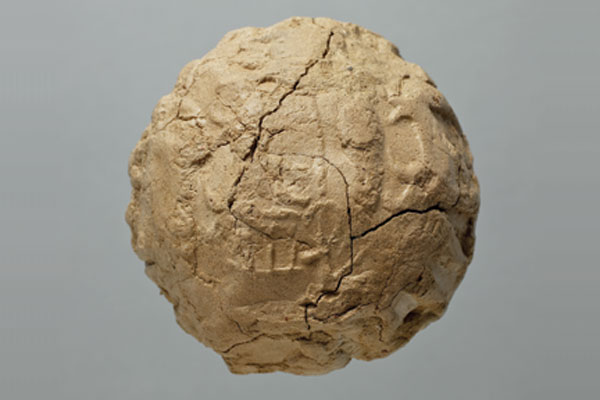

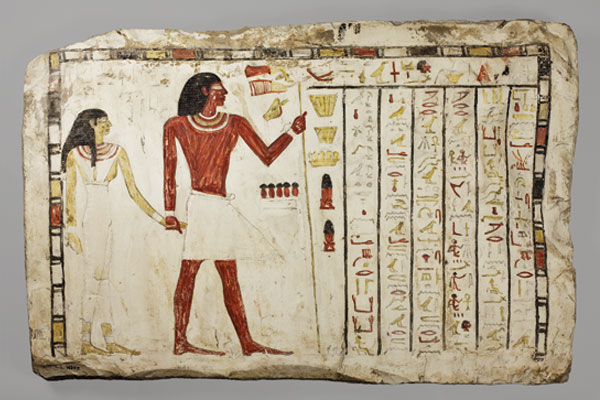

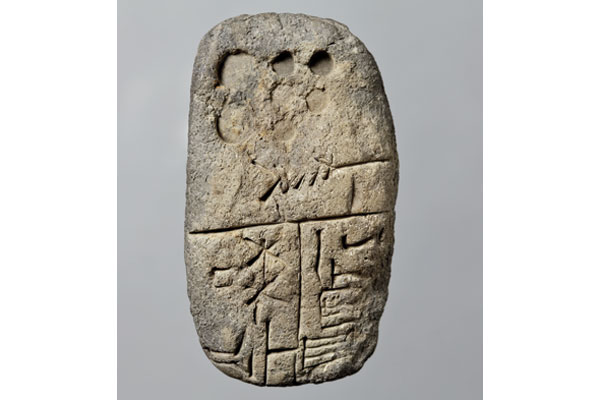

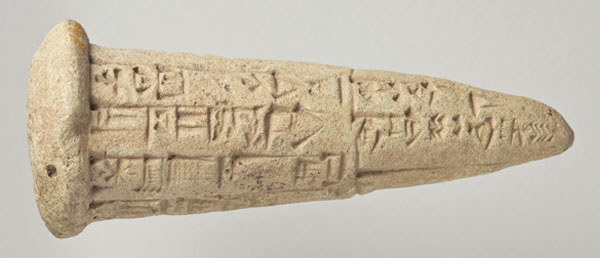

The origins of writing

An Oriental Institute Museum exhibit shows how four distinct writing systems emerged independently.

An Oriental Institute Museum exhibit shows how four distinct writing systems emerged independently.