Investigations

The

discovery of discovery, or our debt to Copernicus

>>The

discovery-and the gradual acceptance of-a heliocentric universe

says a lot about how a society embraces big ideas.

Howard Margolis has made a

bold move. Not only has the public-policy professor stepped away

from his discipline by writing a book about science, but he's

also departed entirely from the prevailing stance among science

historians: that the Scientific Revolution didn't exist.

"This [view] reminds

me of a story of the Old West about a cowboy wandering over the

plateau of northern Arizona," writes Margolis in It Started

with Copernicus: How Turning the World Inside Out Led to the Scientific

Revolution, due out this April from McGraw-Hill. "Innocently

he rides right up to the rim of the Grand Canyon. The cowboy sits

a long time contemplating the vast gorge. Eventually he mutters,

'Something happened here.'"

Something also happened in

Europe around 1600, Margolis says, effecting a permanent change

in the course of scientific discovery-and creating a cognitive

gorge worthy of being called a revolution. Cognitive is

the key term, because what changed, says Margolis, was how scientists

thought about their work. Following Copernicus's lead, in the

early 17th century researchers began an entirely new form of inquiry.

The problem is, he says, science historians take the gorge so

much for granted that it's become invisible.

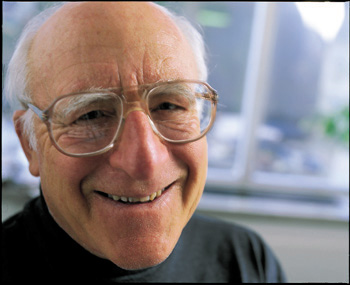

A barrel-chested man whose

fine white hair obeys the whims of the static electricity sparked

by his cyclist's helmet, Margolis loves problems that involve

entrenched and shifting social knowledge. In his peripatetic career

he has been a defense correspondent for the Washington Post,

a speech writer for the secretary of defense, and a fellow at

MIT, where he "stuck around long enough they just gave me

a Ph.D." He has written five books, including Dealing

with Risk: Why the Public and the Experts Disagree on Environmental

Issues (Chicago, 1996).

In It Started with Copernicus,

Margolis recreates the Scientific Revolution's cognitive canyon

by sketching out the events and people on both sides. By the epilogue,

he's speculating on lessons for public policy-and suddenly it

seems he hasn't strayed so far from disciplinary confines.

Margolis's tale begins with

a rather awkward character straddling the canyon. In 1588 the

Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe offered a compromise between two

conflicting systems of the "world": Ptolemy's geocentric

and Copernicus's heliocentric theory. (The idea of a "universe"

hadn't yet been introduced.) Tycho allowed the traditional planets

to orbit the Sun but kept the Sun, carrying the planets' orbits,

orbiting the Earth. In Tycho's sketch, the orbits of the Sun and

Mars seem to intersect-a problem he solved by doing away with

Ptolemy's solid spheres, citing for evidence his recent observations

of a comet whose path through the heavens proved solid spheres

couldn't exist. The compromise was, for some time, the only theory

a God- (and pope-) fearing Catholic-scientist or otherwise-could

in good faith embrace. In the 20th century, the MIT philosopher

and historian of science Thomas Kuhn termed Tycho's elimination

of the solid spheres a paradigm shift.

What's interesting is that

Tycho's impetus to discount the spheres-the colliding orbits of

the Sun and Mars-is in fact an optical illusion. In an April 1998

Nature article Margolis became the first known person to

point out the illusion. (There, he explains how to see it, which

for most people requires taking scissors to Tycho's sketch and

manually making the apparatus rotate, which it does, spheres intact.)

For 400 years the illusion had escaped even the most astute scientists

and historians-as well as Margolis himself, who referenced Tycho's

compromise in his 1987 book Patterns, Thinking & Cognition

(Chicago) and only noticed the illusion while writing a Ptolemaic

tutorial for his 1993 book Paradigms and Barriers (Chicago).

The illusion's mysterious persistence was originally to be the

topic of Margolis's current book.

But the more he studied the

phenomenon, the more interested he became in the larger question

of why, by the late 16th century, astronomers' "habits of

mind" were shifting away from Ptolemy and towards seeing

the world as Copernicus saw it. Since Tycho was a symptom of this

larger shift, Margolis set aside the curious illusion and turned

instead to Copernicus.

In 1543 the Polish astronomer

Nicolaus Copernicus published De Revolutionibus, proposing

that the Sun is the fixed point to which the planets' motions

refer and that the Earth itself is a planet that also orbits the

Sun annually. Shocking ideas, yes, says Margolis, but it's Copernicus's

method that precipitated a revolution.

The schism lies between Ptolemy's

what-you-see-is-what-you-get method of direct inquiry and what

Margolis calls Copernicus's "around-the-corner inquiry."

When Ptolemy traced the planets' paths from month to month and

year to year, he saw that they looped like pretzels. He explained

the loops by embedding an epicycle within each solid sphere, like

a circular track mounted on a merry-go-round platform. If a toy

train chugged around the track as the merry-go-round whirled,

Margolis explains, the train would trace out looping motions like

those seemingly traced by the planets.

Copernicus had a hunch that

a simpler explanation lay behind this clumsy apparatus. What Copernicus

found in pursuing his hunch was "not the heliocentric idea

but a reason to take that idea seriously," writes Margolis:

"that if the Earth might orbit the Sun, then the looping

motions of the planets would be reduced to mere illusions of parallax."

Copernicus had an unwitting helpmate: Columbus, whose westward

path in 1492 proved the flat Earth actually had a backside. It

took until 1508 for this second continent to be published as a

map-and find its way into the astronomer's library. If the Earth

were round, suddenly the possibility that it also moved wasn't

so ludicrous.

Copernicus discovered a reason

to take the heliocentric idea seriously because he "had the

boldness to look around a corner no one else had thought to explore,"

thus initiating the crack in scientific inquiry that would strand

Ptolemy on the other side. Such inquiry, Margolis argues, "turns

discovery in science from a process which needs an epiphany...into

a process that might sometimes (or even ordinarily) need two or

more epiphanies: the promising hunch, then eventually another

hunch about where to look for some striking evidence or novel

argument that could support or clarify or (also crucial, since

that is often what it deserves) embarrass the original hunch."

Epiphanies, he continues,

"only come to people who have been persistent in thinking

hard about relevant things. Hence that second epiphany only comes

to someone alert to the likelihood that a second epiphany is just

what is needed."

What changed around 1600,

then, writes Margolis, "was not something explicit but a

habit of mind," which we take so much for granted nowadays

that the shift required to embrace it has become invisible. As

evidence, he cites four scientists whose methods were strikingly

similar: Simon Stevin, the Flemish mathematician who demonstrated

the law of free fall; William Gilbert, the British physician who

proposed that the Earth is a magnet; Johannes Kepler, the German

astronomer who discovered the elliptical paths of the planets;

and Galileo, the Italian astronomer and mathematician who made

fundamental contributions to the development of the scientific

method. All were either explicitly or implicitly Copernicans.

Why did it take until the

early 1600s for scientists to follow Copernicus's 1543 lead? Here

Margolis describes a peculiar quirk of social knowledge. "When

something takes hold as social knowledge," he explains, "it

begins to seem automatically both more economical and more comfortable."

These are the two conditions, he says, under which people-scientists

included -make up and change their minds. "Sometimes logically,

sometimes merely by trained inattention, we learn to ignore aspects

of it that might otherwise seem clumsy." The heliocentric

idea, he suggests, had simply been around long enough that it

was no longer so shocking, and Tycho had primed the pump with

his compromise, illusory though it was. Copernicus's theory was

clearly economical in the way it untied the pretzels, and by the

early 1600s it was comfortable too.

Yet despite this shift, Tycho's

illusion went unnoticed. Why? Because humans, even brilliant ones

like Kuhn, are not always rational, argues Margolis, who is among

a growing group of academics studying the tendency to be irrational-or,

as he puts it, "illogical, and more often so than we can

notice." He cites the passionate debates recently sparked

by the findings that having mammograms does not prevent women

from dying of breast cancer or help them avoid mastectomies. "If

you read the study, it makes logical sense," he explains,

but people don't want to let go of a "cognitive illusion"-that

having regular mammograms will keep them healthy-they'd trusted

for so long.

With It Started with Copernicus,

Margolis shows that everyone is susceptible to illogic-mathematicians

and astronomers, popes and peasants. The next task for academics

who study public policy, he says, is to sidle up to a Grand Canyon

and figure out what happened there.

-S.A.S.

![]()