|

|

| Where the action was continued...

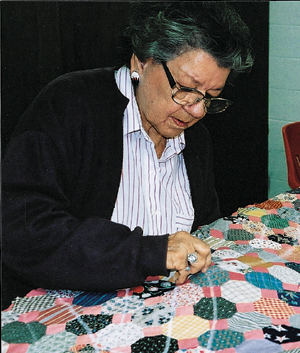

Other projects were more ambitious. In 1955 project director Robert Reitz helped local artist Charles Pushetonequa and other Meskwaki craftsmen to start a cooperative that produced greeting cards and decorative ceramic tiles with images from Pushetonequa’s paintings. The business, known as Tama Indian Crafts, or Tamacraft, attracted more workers than could be included and initially flourished, selling its products to gift shops around the country. To the Chicago students, however, Tamacraft’s chief benefits were psychological and social, increasing self-confidence and community pride. The Meskwaki, noted a Fox Project report, “have been eager to take part in Tamacraft as the sort of thing which is precisely what they want to do—become respected participants in Iowan citizenship without having to die as a nation to do it, without having to lose their identity.” But management difficulties and a lack of capital undermined the cooperative’s successes. “You couldn’t get anybody to do anything,” says 78-year-old Jene Waseskuk, whose family was in the cooperative. “I trained three or four people, but they weren’t getting paid, so they dropped out. We just couldn’t get our head out of water.” In another mid-1950s effort, the Fox Project raised money from the Gardner Cowles Foundation and local Iowa organizations for a scholarship program that eventually sent 18 Meskwaki to Iowa colleges and universities. In hindsight such projects seem relatively insignificant, and not everyone embraced action anthropology at the time. “The kinds of problems the Fox tribe had were really not the kind that a relatively small group of anthropologists, even if well financed, which we weren’t, could do much about,” says Walter Miller, AM’49, an anthropologist who was in the first group of students. Just getting to a position of influence was difficult. “The Fox traditionally were very stubborn, very resistant to outside groups,” he says. But even those students who pursued conventional research helped illuminate issues central to action anthropology. Miller, who later spent a full year on the settlement, studied problems of authority and collective action. Charles Leslie spent his summer there learning about the pow-wow, which, like the Meskwaki religious ceremonies, illustrated how leadership worked informally and in nonauthoritarian ways. Lucinda Sangree compared etiquette among Meskwaki and white teenagers at the Tama high school, believing that intergroup conflict arose “partly because they had different understandings of what was the right thing to do.” To some Fox Project students, Tax’s approach seemed alarmingly free-wheeling. On one of his occasional visits from Chicago, the professor asked how things were going. “We don’t know how we’re doing,” Leslie confided. “Great!” Tax replied. “That’s how things ought to be.” Uncertainty and improvisation were part of his method. In theory, at least, the anthropologists should resist the impulse to impose their own ideas, letting the Meskwaki make their own plans. Action anthropology, he argued, would help them make freer choices about their future. In practice this theory required considerable restraint. The students constantly worried about whose values they were asserting and who was defining the ends and the means of their work. Independent historian Judith Daubenmier, who has studied the Fox Project field notes, now in the Smithsonian Institution archives, says, “They tried hard not to foist themselves on the Meskwaki.” Fred Gearing, still remembered gratefully by some tribe members for supporting the American Legion, plays down his contribution. “I was just sort of around and sort of helping,” he says. “I would spill a little cement here and there. I don’t know of an instance where people asked my advice about something. I might have nudged them a little bit—‘Why don’t we do this painting?’ It was on that level.” To reach meskwaki settlement, a visitor from Chicago follows U.S. 30, the Old Lincoln Highway, as it heads west across a sea of corn and soybeans. Near Tama the land rumples, and the Iowa River bottomlands come into view. A weathered, wooden profile of an Indian wearing a war bonnet stands beside the highway, just before a billboard declares, “Rich traditions begin at Meskwaki Bingo Casino Hotel. Ahead 7 miles.” No warning is needed. Marked by a glittering marquee that would not be out of place in Las Vegas, the casino stands five stories tall—and is surrounded by acres of empty parking lot. The empty lot is the first sign of a political crisis gripping the settlement. In spring 2003, as accusations of corruption swirled about the elected tribal council, a group of conservative Meskwaki took over the tribal center and the hereditary chief, Charles Old Bear, appointed new council members. But the U.S. government refused to recognize the appointed officials, and federal marshals shut down the casino. October elections gave the appointed council official legitimacy, but in December the casino remained closed. (It reopened New Year’s Eve, though the power struggle continues.) Meanwhile, life on the settlement goes on: Pickup trucks raise clouds of dust as they speed down gravel roads. Employees of the Meskwaki housing office work on new homes. The senior center serves its daily noon meal. In the tribal offices—a large brick building with U.S. and Meskwaki flags flying out front—the tribal historian, Jonathan Buffalo, a friendly man with glasses and a long ponytail, works in an office on whose walls hang two United States maps. One shows American Indian land claims; the other is freckled with red dots marking museums that hold Meskwaki artifacts. In his 40s, Buffalo is too young to remember the Fox Project, but he notes: “I’ve never heard anyone say bad things about it. I’ve just heard mentioned that there were these people here, they studied the tribe, and they left. It was mostly personal relationships with individuals.” The building Fred Gearing helped turn into an American Legion center is gone. The kiln where craftsmen fired tiles burned down in the 1960s, although a small collection of their work is displayed in the office lobby. The poverty of the ’40s and ’50s has receded. Most families live in new one- or two-story houses with air conditioning, a wide-screen TV, and a late-model truck or SUV parked outside. The casino, which takes in $3 million a week, has raised the tribe’s standard of living beyond that of most of Tama’s middle-class residents. Many Meskwaki who knew the students have died. For those still alive, more profound events—such as the long struggle to save their tribal school—have eclipsed memories of the Fox Project. Yet the students are not forgotten. At the senior center Geneva Papakee, 65, a short, friendly woman with curly hair, laughs. She visited them “probably every chance I got,” she says. “They had something going for us. Otherwise we would be staying home. All the high-school students were there.” The students were different from local whites, recalls Bernard Papakee, 74. “They were kind of open-minded,” he says. “Plus, they came from other places. They didn’t come from around here.” But some on the settlement worried about the students’ influence. Marge Mauskemo, 67, remembers that her grandmother disapproved of her visiting the farmhouse: “My grandmother said, ‘You shouldn’t go to them. You shouldn’t go learning those white dances.’ But it was fun when I went.” The Meskwaki reacted to being studied with degrees of tolerance, humor, wariness, and resentment. When Patricia Brown’s mother invited students in, her father left the room. “He didn’t want to share his knowledge with anyone but his own people,” she says. Her own feelings were more complicated. “I accepted them, but deep down I was resentful to be a case study. It was an invasion of privacy. ‘What are you going to do with that?’ That’s what I kept asking. I would say, ‘After you get done studying these people, I hope you’ll come back and help us—after we helped you.’ My mother used to say, ‘Shush.’ But that’s how I felt.” Often familiarity bred affection and overcame reserve. “Everybody is suspicious of people who come here,” explains Everett Kapayou as he sits in his basement bagging empty soda cans for recycling. “What’s this guy doing here? What’s he trying to get off of me?” Still Kapayou, 70, visited the students often. “They were my friends,” he says. “They were nice people.” Most students didn’t stay long. “They’d come and go,” says Bernard Papakee. “You’d meet one person, get to know him, and he’d go back to Chicago.” Some friendships lasted. Papakee traveled to an Apache reservation in Arizona and then to the University of Virginia to visit a student he had met. Patricia Brown corresponded with Marjorie Gearing and sent Grace Harris home with an apron, appliqued in the Meskwaki style, to remember her by. But, Brown says, “They never seemed to keep in touch with us.” The Fox Project changed several Meskwaki lives more dramatically. Don Wanatee, 70, received a college scholarship that started him on an erratic but ultimately successful academic career, culminating in two master’s degrees from the University of Iowa. A tribal leader, an advocate of American Indian education, and a controversial figure on the settlement, Wanatee recently ran for the Iowa state senate (he lost). “I didn’t plan on going to college,” he says. “But one of the things that prompted me, got me interested, was the University of Chicago scholarship program.” Other students didn’t or couldn’t finish. David Old Bear, who lives in a tree-shaded hollow deep in the settlement, attended Parsons College for three semesters. When the funding stopped, he joined the Marines and served in Vietnam. “None of my people had been to college,” he says. “Until that time we never had any scholarship money to go anywhere. My mother encouraged me to get an education to get a better life. I liked it. I was on the track team and ran cross-county. I enjoyed the instructors.” Old Bear was angry that the scholarships had dried up; if he had finished, he thinks, he might have become a teacher. Later he urged his own children to attend college. “I told them, “If anyone wants to go to college, I’ll buy a car so they can come back on weekends.’ Nobody took me up on that. They didn’t think I was serious.” By then there were ample jobs on the settlement. What happened to an approach that seemed so promising in the summer of 1948? In the academy there were theoretical objections to Tax’s abandonment of scientific detachment. What if he were studying a tribe of cannibals? a colleague asked Tax. Would he help them too? He could only answer that among the Meskwaki he did not face that dilemma. But action anthropology encountered resistance beyond skepticism about methodology. Tax was working against the whole current of postwar anthropology, which aspired to discover universal laws of human culture, not dirty its hands with social work. “It was an enormously hostile environment,” says Douglas Foley, a University of Texas anthropologist who has written about the Fox Project. “It took a lot of guts for Tax to do this.”

There were other reasons. Although Tax insisted that action anthropology gave equal emphasis to helping and learning, the Fox Project students never found this balance. They published relatively little: a documentary history of the project, a few articles, and a slim account of the tribe’s predicament (Fred Gearing’s The Face of the Fox, published in 1970). “In a sense, they fulfilled doubts by not producing a high-quality ethnographic portrait,” Foley says. “They got busy doing social work and helping people.” Tax’s own career may have helped doom action anthropology. Enthusiastic and untiring, he was a gifted organizer, at work on many fronts. In 1957 he founded the journal Current Anthropology, and during 17 years as editor he helped make anthropology a global discipline. In 1961 he organized the American Indian Chicago Conference, a pivotal event that for the first time brought together tribes from across the nation. Tax’s entrepreneurial talent earned him numerous honors, but skeptics, including some in his own department, felt that his organizational work came at the expense of his research. The real legacy of the Fox Project, historian Judith Daubenmier believes, was its influence on Tax and, through him, on U.S. Indian affairs. Tax used his standing as a anthropologist to oppose termination policy—the government’s 1950s attempt to force assimilation by ending tribal status. He also promoted education and defended the principle that American Indians run their own affairs. “The Meskwaki really taught Sol Tax how to work with Indians,” Daubenmier says. “But in a larger sense the project gave Tax a lot of credibility when it came to matters of Indian affairs. He became known as somebody who worked with Indians. He had a lot of influence on a lot of ideas that were being discussed in Indian policy. He learned things in Tama that he took to a national level.” In the decades since the project ended, action anthropology has been assessed and re-assessed. Recent scholars have been kinder than Tax’s contemporaries. Time may have vindicated him. In the late 1960s a new generation began again to confront anthropology’s ethical dilemmas, prompted in part by Vine Deloria Jr.’s 1969 book, Custer Died For Your Sins. As a result anthropologists now take for granted that they are obligated to the people they study. Indeed the modern ethic goes well beyond what Tax envisioned. In many cases anthropologists put themselves wholly at the service of the groups they study, who determine what they may and may not inquire into. Nearly a half century has passed since the last U of C students left the settlement in 1958. Many who participated in the project have died. Most followed careers that diverged widely from their beginning experience with action anthropology. Fred Gearing, for example, ended up studying peasants in a Greek village where, he says, the idea of offering to help was unthinkable. Walter Miller became an expert on American gangs. But the Fox Project left lasting memories, including some useful lessons. Grace Harris’s experience, she says, reinforced her natural anti-romanticism. “Life is real, life is earnest, and the Meskwaki taught me that.” She still keeps the apron Patricia Brown gave her, folded in a basket on top of her refrigerator. Sol Tax’s organizational accomplishments inspired Charles Leslie long after he ceased thinking about the Meskwaki. Though now skeptical of many Fox Project ideas, Lucinda Sangree cherishes “the ethical core” of Tax’s approach. Gearing feels guilty that he lost touch with the tribe. In retrospect the students profess mixed feelings about action anthropology. It was possible in theory, Gearing says, but difficult in practice. He was too busy organizing action projects to do much anthropology. “I always thought that any old-time anthropologist would not have liked what he saw.” Lisa Peattie, whose sympathies helped launch action anthropology, thinks it overreached. “I slowly came to the view that I was—we were—assuming capabilities we didn’t have—that I didn’t have,” she says. But the effort addressed a problem that will not go away: “It’s the old question of what does thought do in the world,” she says. “It wasn’t a particularly successful answer. But anyone who does any thinking has to ask the question from time to time.” The Meskwaki also have moved on. Old problems have reappeared in new guises—issues of leadership, authority, and collective action, as well as the larger dilemma of how to remain Meskwaki in a white-dominated world. Fewer children speak the language, and it is a rare youth who can sing the old songs at tribal ceremonies. Intermarriage brings increasing numbers of non-Meskwaki onto the settlement, creating anxieties about the dilution of native blood and raising questions about who really belongs to the tribe. And while the casino has brought unforeseen wealth, some elders worry that prosperity threatens traditional culture more than missionaries and government agents ever did. Which may be why Meskwaki historian Jonathan Buffalo sees the Fox Project as only a blip in the tribal record, one of a long series of encounters with whites, some well-meaning and some not, that has marked the tribe’s history over four centuries. The Meskwaki endured it, took what they could, and continued their lives. “We’ve always been adapting to different people—the French, English, Americans, even a group of University of Chicago students,” Buffalo says with a wry smile. “They came, and they left. We accommodated them, and one day they left. And we’re still here.” Richard Mertens is a freelance writer and a doctoral student in the Committee on Social Thought.

|

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu