Consuming

Interests

>> Focus

groups, brand image, and other staples of modern advertising all

sprang from the work of a group of Chicago social scientists.

These pioneering market researchers used tools from psychology,

anthropology, and sociology to study a once-neglected topic: why

people buy stuff.

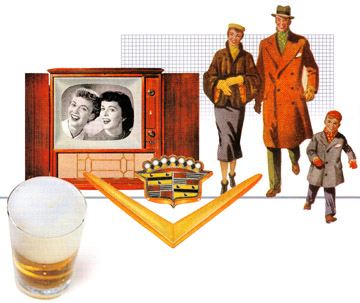

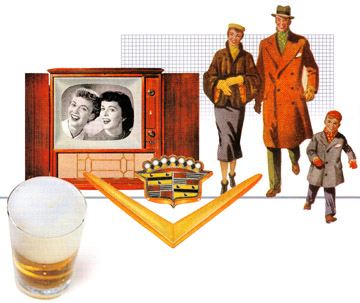

BEER,

ACCORDING TO EXPERTS, "is

not a prestige item." There's nothing distinctive or exclusive

about it. Cheap and widely available, it does not require stylish,

single-task glassware, like Champagne flutes or brandy snifters,

but can be consumed from plastic mugs, recycled jelly jars, even

straight from the can or bottle.

BEER,

ACCORDING TO EXPERTS, "is

not a prestige item." There's nothing distinctive or exclusive

about it. Cheap and widely available, it does not require stylish,

single-task glassware, like Champagne flutes or brandy snifters,

but can be consumed from plastic mugs, recycled jelly jars, even

straight from the can or bottle.

Regular

beer drinkers, social scientists agree, "do not fall all

over themselves" to imitate high society. They rarely dress

for the occasion. They may not even wear shirts. They drink beer

to quench their thirst, to relax, to grease the wheels of social

interaction and unleash spontaneity.

Beer

"marks the absence of power relations, authority, or social

striving," says the foremost study of the subject. Beer advertisements

that cater to status seekers-depicting sophisticates in elegant

settings and formal attire, sipping this chilled, golden beverage

while basking in the good life-evoke only hostility among beer

drinkers. "Oh, the Ritzy Bitches like beer" is a typical

response, or "I'll bet one stinking glass of beer costs half

a buck in a place like that."

As

the price reveals, this is not a recent study. But what students

of consumption now call the "use code" of beer hasn't

changed much since a cluster of curious Chicago social scientists,

assisted by a handful of graduate students and 350 hard-drinking

Chicagoans, probed the beer-buying world in the early 1950s.

The

researchers belonged to a small firm called Social Research, Incorporated-SRI

for short-housed in the Hyde Park Bank building on 53rd Street.

They veered off from the University in 1946 to form the company

almost by accident, when a series of coincidences and opportunities

made a venture into the commercial world seem like a very good

idea indeed.

Over

the next two decades SRI helped to revolutionize the field of

market research, transforming its assumptions, methods, goals,

and consequences in ways that quickly redirected the world of

advertising and slowly, very slowly, made consumption-"the

most studied single phenomenon in American life," according

to Andrew Abbott, AM'75, PhD'82, chair of sociology at Chicago-a

focus of purely academic inquiry.

The

SRI team did it by applying social-science techniques to what

was then a neglected topic: why people buy stuff. The researchers

were among the first to adapt tools developed by anthropologists

for the study of primitive societies and use them to investigate

modern industrial communities. They borrowed personality tests

invented by psychologists to probe the meaning of purchasing decisions.

And they applied evolving notions of social status, mobility,

and class aspirations to understand what buying, owning, and displaying

consumer goods meant. In its short life SRI left a lasting impact

on theworld of market research, influences still felt in everything

from the absolute devotion to "brand image," to reliance

on focus groups, to academic study of the meanings of consumption.

The

SRI team did it by applying social-science techniques to what

was then a neglected topic: why people buy stuff. The researchers

were among the first to adapt tools developed by anthropologists

for the study of primitive societies and use them to investigate

modern industrial communities. They borrowed personality tests

invented by psychologists to probe the meaning of purchasing decisions.

And they applied evolving notions of social status, mobility,

and class aspirations to understand what buying, owning, and displaying

consumer goods meant. In its short life SRI left a lasting impact

on theworld of market research, influences still felt in everything

from the absolute devotion to "brand image," to reliance

on focus groups, to academic study of the meanings of consumption.

Market

research, up until the end of World War II, consisted almost entirely

of crunching census data to determine how much of a given product

how many customers might buy. Shaped by the Depression, the field

used simple demographics to gauge often-limited demand for specific

products and to measure response to advertisements. As production

capacity and buying power increased, researchers began to look

for ways to stimulate new rather than measure existing demand.

"Our problem," summarized a senator from Wisconsin,

"is not too much cheese produced, but rather too little cheese

consumed." One component of the post-war effort to peddle

more cheddar was to shift research away from how much consumers

could be expected to eat toward what made them hungry-and how

to make them hungrier-a field that was dubbed motivation research.

"This

is a completely different kind of research," noted the introduction

to SRI's Study of Consumer Attitudes on Beer and Beer Advertising.

"Instead of counting noses, this is diagnostic research.

The analyst is trained to look for basic attitudes, just as a

doctor looks for symptoms." As social scientists, SRI looked

for the social meanings of beer. "The attitudes of different

class levels toward beer," was its driving focus, along with

"the impact of typical beer advertising on different classes."

The

new approach-finding the unconscious, intuitive, emotional factors

that drive consumption at each class level and grafting the most

alluring of those factors onto the product-caught on. By the mid-1950s

most major advertising agencies had hired motivation-research

consultants or had recruited teams of "whiskers" from

academia. "More and more advertising and marketing strategists

are adapting their sales campaigns to the psychologists' findings,"

noted the Wall Street Journal in 1954. "Top-drawer

advertising agencies," echoed the trade magazine Printer's

Ink, "favor the increased use of social sciences."

The

commercial success of motivation research soon provoked a backlash.

In 1957, journalist Vance Packard sounded a very public alarm

in The Hidden Persuaders, a book that plumbed the moral

depths of depth analysis and mass marketing while selling more

than 500,000 copies, enough to make it No. 1 on nonfiction best-seller

lists for six weeks.

"The

use of mass psychoanalysis to guide campaigns of persuasion has

become the basis of a multi-million dollar industry," Packard

told his readers. "Large scale efforts are being made, often

with impressive success, to channel our unthinking habits, our

purchasing decisions, and our thought processes by the use of

insights gleaned from psychiatry and the social sciences."

These "awesome" psychological tools and "ingenious"

anthropological techniques have been designed by a "breed

of persuaders known in the trade as the depth boys," he warned.

"Many of us are being influenced and manipulated, far more

than we realize."

Motivation

research was selling us not just goods but also political candidates,

social attitudes, career and personal goals, or states of mind.

"We move into the chilling world of George Orwell and his

Big Brother as we explore some of the extreme attempts at probing

and manipulating now going on," Packard wrote, a world where

the consumer, the citizen, and the voter "more and more is

treated like Pavlov's conditioned dog."

A

caricature of the depth boys even made it into the movies. Putney

Swope, Robert Downey's 1969 dark comedy about the advertising

business, opens with a presentation by Dr. Alvin Weasely, billed

as "one of the most respected motivational researchers in

the world." He has been called in to help a Madison Avenue

advertising agency boost sales for an unpopular brew by explaining

the unconscious motives of beer drinkers. "Beer," Weasely

pronounces, "is for men who doubt their masculinity. That's

why it's so popular at sporting events and poker games. On a superficial

level," he continues, "a glass of beer is a cool, soothing

beverage. But in reality, a glass of beer is pee-pee dickie."

Though

filled with the unexpected, SRI's own in-depth consumer studies

of everything from soap to soap operas, department stores to lumber

yards, and alcohol, tobacco, and fast cars, were never that shocking

or implausible. Its researchers were grounded by a commitment

to serious social research, access to the latest tools of academic

social science, and the bias of the founders toward social class,

not psychological factors, as the basis for understanding consumer

decisions.

The

late-1940s and 1950s were an odd time to fixate on social class.

"The prevailing post-war view," said Kim A. Weeden,

assistant professor of sociology at Chicago, speaking at a campus

conference last fall about SRI and the history of consumer research,

"was that class divisions in America were gradually disappearing."

Many social scientists believed that, with increasing affluence,

the different classes were converging in their culture, lifestyle,

values, and standard of living, but, said Weeden, "there

were of course exceptions."

Perhaps

the most noticeable of the exceptions was a social scientist named

Lloyd Warner-SRI's founder and by all accounts its generative

intellect. Warner, who joined the U of C as a sociology professor

in 1935, had taught SRI's other two founders, Burleigh Gardner

and William Henry, PhD'44. An anthropologist by training, he'd

spent three years as a graduate student doing field work in Australia,

scrutinizing the social structure of an aboriginal tribe. But

he grew less interested in "primitives" and increasingly

convinced that the tools of social anthropology might better be

applied to modern American society-an idea that would not become

popular until the 1970s.

"His

platform," recalls SRI colleague Lee Rainwater, AM'51, PhD'54,

"was that all human life partakes of the same basic species

behavior." If so, then the tools used to understand sacred

tribal rituals or daily routines should work just as well to understand

the Fourth of July or breakfast cereal. When Warner returned to

the U.S. in 1929 to take a position at Harvard, he decided not

to finish his dissertation on kinship among aborigines thousands

of miles away but to focus instead on the social systems of a

nearby small town.

He

quickly became involved in his "Yankee City" project.

With 18 fieldworkers, mostly volunteers, Warner spent four years

(1930-34) studying Newburyport, Massachusetts, using versions

of the methods he had mastered while working with a primitive

tribe: observation, close analysis of social networks, and unstructured

interviews that allowed the subjects to wander wherever their

interests led.

The

result was five books, the Yankee City series. The first volume,

The Social Life of a Modern Community (1941), emphasized the

role of social class as the basic structuring principle of urban

society, as powerful as kinship among Australian tribes. Unlike

the Marxist view, Warner's definition of class was based less

on how people got money and more on how they spent it. The means

of production had given way to the meanings of consumption.

"In

Yankee City," notes Michael Karesh, AM'95, whose well-researched

sociology master's thesis on SRI has triggered a revival of interest

in the group, "different social classes were distinguished

not simply by income but by different goods, behaviors, values,

and points of view. To achieve upward mobility an individual not

only had to earn more money or buy better goods, but perceive,

value, and use goods in a different way. The shiny new Cadillac

of the upper-lower class was no substitute for the history-laden

house and furniture of the upper-upper class. To Warner, these

symbols marked the various social positions in a way that both

sustained the social structure and, for some individuals, allowed

mobility within it."

In

his small-town studies and later in a study of Chicago financed

by the Chicago Tribune, Warner split the population into

six classes-from upper-upper to lower-lower-a rough formula followed

by most sociologists. Although his work created only a "respectful

stir in academic circles," wrote Packard, it churned merchandising

circles to a frenzy and "came to be regarded as a milestone

in the sociological approach to the consumer."

BY

THE TIME

the

first Yankee City volume appeared, Warner had been lured away

from Harvard by Chicago's greater enthusiasm for interdisciplinary

work. He was followed by Burleigh Gardner, a country boy from

Texas who had come to Harvard to study anthropology and wound

up working on the Yankee City studies. Described by Packard as

a "mop-haired, slow-speaking, amiable man," Gardner

was ill at ease with scholarly pretensions and preferred life

on the fringes of academe. But in 1942 he was enticed into teaching

in Chicago's newly created Committee on Human Relations in Industry.

After

reeling Gardner in, Warner stepped halfway out, to consult for

a new company, the Office for the Study of Social Communication.

Despite its scholarly name, the OSSC was started by a greeting-card

magnate to learn more about his customers. Warner and another

former graduate student, William Henry, adapted a series of the

"projective" tests then in use as a way to ferret out

the card consumers' unconscious motives, dividing buyers into

12 distinct personality profiles.

When

those studies were finished, the OSSC dissolved, but in 1946-this

time with backing from Sears, Roebuck-Warner and Gardner formed

their own consulting group, SRI, to help companies investigate

employee and customer attitudes. They brought in Henry, who had

joined the Chicago faculty in 1944, to run the psychological testing.

Gardner, who had quickly tired of academic politics and meetings,

resigned from the University to become SRI's executive director.

It

was the ideal arrangement, argues Karesh. Informally connected

but formally separate from the University, SRI could "acquire

the latest conceptual and methodological tools in the social sciences

and apply them to commercial ends."

The

company quickly made a name for itself in the emerging field of

consumer motivation research, pulling together Gardner's interest

in commercial applications of social science, Henry's expertise

in psychoanalytic testing, and Warner's faith in the crucial importance

of social class.

As

"senior consultants," Warner and Henry spent most of

their time on campus, and Gardner devoted himself to courting

new clients and writing articles for advertising periodicals.

The quotidian work was done by the firm's junior members, grad

students from human development and sociology who needed the money

at a time when there was little funding for graduate study in

the social sciences.

One

of the first students on board, Harriet Moore, became director

of research, supervising staff training and study design and providing

"much of the intellectual force in [SRI's] day-to-day operation,"

according to Sidney Levy, PhB'46, AM'48, PhD'56, another insolvent

grad student who arrived at SRI in 1948. By the early 1950s, the

core staff was in place. Moore, Levy, and Lee Rainwater, who came

in 1950, formed a close trio. Key members Ira Glick, AM'51, PhD'57;

Richard Coleman, PhD'59; and others soon followed. The professional

staff never grew very large, however, topping out at 17 in 1957.

The

period, said Levy, was "the most exciting and intensely absorbing

in my life. We lived SRI from breakfast until bedtime, brooding

over methods and data gathering and seeking penetrating insights."

"Much

of the excitement," notes Karesh, "followed from the

feeling on the part of those involved that they were part of a

pioneering team composed of brilliant minds exploring new intellectual

terrain." Because Gardner had a tendency to accept assignments

without knowing whether SRI could perform them, its members had

to be especially creative. "New concepts and methods were

generated internally," says Karesh, "or borrowed from

the University and then combined and applied in novel ways."

"We

did the first qualitative study for the Coca-Cola company,"

Levy recalled, "on why people drink soft drinks; the first

qualitative study for AT&T on the meaning of the telephone.

For the Wrigley Company we studied what baseball meant to Cubs

fans. A study for FTD, the flower delivery system, analyzed the

poignancy of flowers as symbolic of the life cycle, representing

and celebrating its beauty and fragility and the inevitability

of death."

The

basic approach, said Levy, began with the so-called depth interview,

a free-style open-ended conversation. Sometimes SRI researchers

also interviewed two of three people at a time, or even larger

groups, a technique now known as focus groups. "Within this

more or less non-directive approach we embedded various projective

devices," he recalled, including variants on such clinical

techniques as the TAT, the Rorschach, sentence completion, word

association, draw a person, "and even the curious Szondi

test," now discredited, in which an individual was shown

eight photographic portraits and asked to choose the person he

would most, and least, like to sit next to on a long trip. The

twist was that each picture portrayed a person with a major psychiatric

disorder. A subject's selection was thought to reveal something

about the chooser's psychological needs.

The

hallmark of SRI was its compulsion to assess the social status

of every subject. "We took pictures of people's houses and

living rooms," said Levy. "We sent interviewers to spend

whole days observing. We classified all our respondents so we

could examine the effects of social class on consumer behavior.

And we taught our clients about social stratification and the

structure of American society."

SRI

WAS NOT THE NATION'S

first motivation research firm. There was a rival New York academic

group, the Bureau of Applied Social Research. Led by Paul Lazarsfeld,

a psychiatrist and mathematician from Vienna, BASR was closely

tied to Columbia University. Lazarsfeld, arguably the field's

first scholar, began writing about the psychology of market research

as early as 1934. But he got there "too early" for commercial

success, suspects Karesh. The research tools and the market weren't

ready. BASR survived into the 1960s but never developed SRI's

commitment to clients or freedom from university bureaucracy.

It didn't help that its best-known project was the Edsel.

One

of Lazarsfeld's students had better timing. Ernest Dichter came

to the U.S. from Vienna in 1938. In 1946, after a series of jobs,

he started his own consumer research firm, the Institute for Motivation

Research. By the early 1950s the firm's success could be seen

in its glitzy headquarters, a 30-room, hilltop mansion just up

the Hudson from Manhattan. By 1956 it had conducted more than

500 studies, and by 1964 more than 2,500. Dichter, "a jaunty,

exuberant, balding man," who called himself Mr. Mass Motivation,

was the prime player in Packard's book, bragging that he maintained

a standby "psycho-panel" of several hundred families,

"whose members have been carefully charted as to their emotional

make up."

The

Chicago version of Dichter was Louis Cheskin, director of the

Color Research Institute of America. Cheskin claimed to have begun

motivational research in 1935, when he backed into the field from

the area of package design, where he emphasized the role of color.

(We have him to thank for tinted toilet tissue.) His most famous

contribution was the sex change he performed for Marlboro cigarettes.

The brand was originally designed to appeal to women, with red

paper to mask lipstick smears. But far more men smoked. So Cheskin

designed a manly package and helped devise an ad campaign based

on "man-sized flavor," featuring rugged men, mostly

cowboys on horses. The men all had tattoos, to lend them a "virile

and interesting-past look." The ads still run. And Cheskin

Research, now headquartered in Redwood Shores, California, still

exists.

While

Dichter and Cheskin were all business, most staff at SRI, despite

the income that came with commercial success, remained scholars

at heart. "As social scientists," recalled Levy, "we

were not content just to write proprietary research reports for

our clients. We thought about the larger implications of our specific

research projects," publishing regularly and presenting at

scholarly conferences.

In

combining commercial and academic pursuits, SRI managed to unite

two formerly unconnected words into a phrase that ultimately defined

consumer research, and has shaped marketing ever since. Levy officially

coined the term "brand image" for an article he and

Gardner wrote in 1955 at the request of the Harvard Business

Review. They defined it as the "sets of ideas, feelings

and attitudes that consumers have about brands." But the

term also took in consumer impressions about who might be expected

to buy the product and what buying it told the world about the

owner.

"Each

product or brand exists in people's minds as a symbolic entity,"

recalled Levy, "an integrated result of all their experiences

with it in the marketplace." This meant that advertisements

could no longer just be about the merits of a product or about

price but had to enhance the product's aura. They were "an

investment in the long-run reputation of the brand." Like

a good Chicago student, Levy traced this notion back to three

sources: Plato's concept of an idealized form, William James's

musings on the social self as a consequence of recognition by

others, and his own study of the pert and perky personality of

Betty Crocker, a kitchen-bound homemaker who existed only as a

picture on General Mills packaging.

The

first SRI report to mention brand image was "Automobiles-What

They Mean to Americans," a 1954 study commissioned by the

Chicago Tribune and instantly scooped up by contemporary

marketing journals. This was SRI's optimal subject. "The

American prizes his car above every possession," proclaimed

Pierre Martineau, director of research at the Tribune and

a fervent advocate of motivation research. "No other consumer

good at the time," argues Karesh, "was more heavily

laden with symbolic qualities."

The

report was the first study to delve into what a product revealed

about those who bought it. "We fit people into slots by the

kind of cars they drive," notes the report. "The automobile

has come to be one of the most important ways we have of revealing

characteristics and feelings and motives. The car tells what we

want to be-or think we are."

The

researchers found that a product's personality could be just as

important as performance or price. In fact, very few consumers

in the study, mostly lower-class men, had any real interest in

the technical aspect of new cars. Rather, the buying process came

down to "an interaction between the personality of the car

and the personality of the individual."

The

researchers presented personality profiles for 18 domestic cars,

assessing the social status associated with each and combining

that with personality factors tied to make, color, and accessories,

rating cars for prestige and ability to attract attention-and

how they did so. Was a car overtly ostentatious, fairly flashy,

slightly stylish, or consciously inconspicuous?

Take

the Cadillac, "America's dream car." Cadillac conferred

the highest status, offered the most luxury, was seen as the best

built of any U.S. automobile. On the down side, many people resented

it as too snobbish or snooty. It was the car for new money, for

those who needed the status boost, especially "people of

deprived origins." The truly rich, SRI reported, the upper-upper

class, wouldn't go near it; they drove beat-up old station wagons,

displaying their indifference through deliberate downgrading.

Buicks

were socially a notch below Cadillac but for those on the way

up. They were seen as reliable, sturdy cars for substantial people.

Fords were for the young, singles, hot rodders-fast, flexible

and rugged, chic, modern, and a bit showy. Plymouths were sensible,

inexpensive, small, with neutral styling. "Plymouth receives

very little criticism," noted the report, "but neither

does anybody get wildly excited about it." Shortly after

the study came out, the Chrysler Corporation, Plymouth's maker,

overhauled the image of all its cars.

Thanks

to the press from studies like this and a flurry of customers

inspired by The Hidden Persuaders, SRI was extraordinarily

busy throughout the late 1950s. In 1960 the firm was able to return

Packard's favor; it made one of his most ominous predictions come

true.

"To

get some publicity," recounted Lee Rainwater, "and to

satisfy our own curiosity, and to overcome the prejudice against

a Catholic in the White House," an SRI team analyzed the

1960 presidential candidates Nixon and Kennedy. They found that

Kennedy had one serious weakness, the perception that he was too

immature, too subordinate to his powerful family.

The

key to changing this perception, they decided, was to build up

JFK's stature as the head of his own independent family through

the popular image of his spouse. The Democrats had to show that

Jacqueline Kennedy was a capable, intelligent, accomplished wife

and mother. Warner drew up a memo that sketched out ways to do

this and took his proposal to friends in the Kennedy campaign.

They went over it in detail with Mrs. Kennedy, then arranged for

her to do a series of televised interviews. Kennedy, of course,

won by a narrow margin. How much difference SRI made will never

be known; there was no funding for a follow-up evaluation.

THROUGH

THE YEARS,

SRI's work largely remained outside the academic pale. Graduate

students could not get credit for their SRI research, no matter

how clever, or use SRI data for scholarly analysis. And interest

in the cultural properties of consumer goods was still seen as

"intellectual slumming" by serious scholars, said anthropologist

and consumption scholar Grant McCracken, AM'76, PhD'81, author

of Culture and Consumption (as well as a work with a less

intimidating title, Big Hair). Studying what people buy

was seen as applied rather than pure research, tainted by contact

with the business world, an elitist bias that has "kept social

scientists away from consumer research for decades."

For

a while, SRI brought both sides together, but not for long. Several

staffers, those who never finished their dissertations, were devoted

to commercial work. A few left to start their own firms. Others,

like Warner, retained a primary commitment to scholarship. Lee

Rainwater and Richard Coleman managed to produce scholarship while

at SRI but were increasingly frustrated by the confidential nature

of most of their applied work.

Rainwater

left in 1963 to teach sociology at Washington University in St.

Louis, joining Harvard in 1969. Coleman quit SRI in 1969 for the

Joint Center on Urban Studies at MIT and Harvard, moving on to

teach marketing at Kansas State University. Originally captivated

by commercial work, Levy migrated to the academic camp and joined

Northwestern's marketing department in 1961, becoming its chair

in 1980.

As

social-sciences funding increased in the 1960s the firm's supply

of student talent dwindled, and in the 1970s newer, computer-driven

quantitative techniques triumphed over SRI's highly interpreted

qualitative studies. By the mid-1970s the firm existed in name

only and motivational research had lost the limelight. It had

answered the questions that it could, then gave way to other forms

of consumer research.

Corporate

interest in consumer motives never wilted, however, and interest

in consumption research slowly crept into favor in academe. The

Association for Consumption Research, the first organization of

academic researchers in the field of consumer behavior, was founded

in 1971. Anthropologists began to take Warner's lead by studying

their own societies, and the social sciences as a whole began

to acknowledge consumption as a legitimate topic-although they

maintained their distance from applied or marketing research,

a stance that often forced them to reinvent established techniques.

Societal

and academic interest in social class also began to rise in the

1970s, but it focused more on poverty and extreme wealth, people

at the fringes rather than the middle majority, and thus had less

impact on marketing. Richard Coleman humbly noted at the SRI conference

that his 1983 article, "The Continuing Significance of Social

Class to Marketing," was ironically the last article ever

published by the Journal of Consumer Research to feature

social class as a major variable.

Indeed,

Warner's six-category system of class now seems somewhat simplistic.

"Where," wondered Coleman, "would most Americans

place the high-income nerds of Silicon Valley?" Today researchers

stress the emergence of overlapping or competing hierarchies.

Just as there are now several hundred television channels catering

to very specific interests, instead of the former big three networks,

there are multiple vertical as well as horizontal social clusters,

each with its own internal rankings. "Class takes a back

seat to racial identities, gender, ethnic heritage, or religious

identities," said Weeder. "Labor is out, feminism is

in."

Even

the car market is "no longer that useful in studying social

class," said Coleman. "Now, what people want has very

little to do with class. It has to do with whether one wants to

feel sybaritic or sexy or whatnot."

"As

a practitioner," said Leo J. Shapiro, AB'42, PhD'56, founder

of a market research firm that competed with SRI, "and I

am about as pure a practitioner as you will find," he told

the conference, "I can tell you that Lloyd Warner's concepts

and techniques were adopted commercially and used by practitioners

and academicians, but they are no longer relevant." That

is not because they don't explain things about society or help

us anticipate the future. "They are no longer relevant because

they have been displaced by more economical techniques."

Social

research by practitioners, he explained, is not about discovering

profound insights. It is about finding some tiny new thing that

gives the client a competitive edge, "a little bit of truth

that will let him get his money back." Why use something

as stunningly complex and costly as class if you can plug in a

much simpler variable and get similar results?

A

much simpler-and thus more efficient-variable is knowing who the

people are who buy what you sell. This information is increasingly

available, thanks to the spread of catalog shopping, electronic

transactions, loyalty incentive cards in stores, and the Internet.

"The ultimate unit for analysis is not the person,"

said Shapiro, "but the act."

And

each act is being recorded. "There are data sets that include

every single electronic act of consumption for the last several

decades," noted Abbott. "Let me assure you," said

Jonathan Frenzen, AB'78, MBA'82, PhD'88, clinical professor in

the Graduate School of Business, "Big Brother is watching,

and he is watching increasingly effectively." Once you purchase

clothes via catalog, he emphasized, the vendor knows your address,

your VISA number, exactly what you purchased, and your measurements.

Shopping

on the Web reveals even more, he added. Marketers can track your

click stream, "where you go and how long you pause on each

page." Amazon.com, for example, uses a technique called collaborative

filtering to chart your purchases and then suggests other books

that are somehow related, items already purchased by people who

look, at least to Amazon, a lot like you.

It

works. Two weeks before a book on healthy eating by the University's

Michael Roizen was published, Amazon e-mailed everyone who had

bought the doctor's previous book on healthy aging, or any similar

book. Without a single ad or book review, even before the book

was released, it was a top-five seller for Amazon. "This

kind of behavior," predicted Frenzen, "is soon going

to follow you to the browser in your car."

In

an odd way, such focused data gathering may lessen the hovering

menace of Big Brother's constant attention. While SRI's researchers

wanted to know everything about a few representative customers,

current commercial consumer research concentrates on very specific,

isolated acts of millions of essentially classless and faceless

customers.

This

might be one more reason that consumption has remained so long

outside the academic universe. The consumer research industry

collects staggering volumes of information, figures that may be

extremely important if you're paid to sell a product but, details

that, said Frenzen, "may be viewed as being simply too trivial

for academics to worry about."

If

social science has been slow to embrace commerce since the emergence

of firms like SRI, commerce has fallen head over heels for social

science. "Ten years ago I told Andy [Abbott] there was more

social science done outside academia than within universities,"

said Eric Almquist, head of the customer management team for Mercer

Management Consulting. Today market research is a $14 billion

industry. By 2003 the total will reach $21 billion.

"Social

science is central to business," argued Almquist, "and

growing even more central. Winning and losing in market capitalization

is increasingly determined by how well companies anticipate changes

in the marketplace, a social science issue."

Almquist

recently completed a study that looked at sudden drops in corporate

share price. Over the last five years, 10 percent of the Fortune

1000 companies lost more than one-fourth of their shareholder

value within a month. "These are what we call value collapse,"

Almquist said. "Customer research turns out to be the single

biggest thing companies

could have done better to avoid this catastrophe." Rubbermaid,

for example, lost touch with one customer: Wal-mart. For Readers'

Digest the major problem is age. Their consumers are aging

"faster than time," explained Almquist. "They have

retired permanently."

His

own firm uses modern economic techniques such as discrete-choice

analysis to measure effects created by brand image as defined

by Levy and Gardner in the mid-1950s. "We've been trying

to push their insights further," Almquist said, "and

to link brand image to demand curves." Researchers now can

decipher exactly how much a brand's image is worth, how that image

shifts demand toward or away from the brand. If the brand's appeal

goes up, the company can raise the price, or sell more goods.

The

best example is motorcycle maker Harley-Davidson, which, according

to Almquist, has the world's strongest brand image. While a Harley

costs $18,000, the Japanese equivalent runs about $6,000. Yet

Harley, at three times the price, "does not have the quality,"

said Almquist. "Harleys have more problems. They require

more service. You have to wait six months to get one." But

if you're serious about the biker lifestyle, freedom, the open

road, and bugs in your teeth, you do not buy the Japanese knock-off

because it is not a Harley-Davidson. You don't see many people,

he added, with Yamaha or Suzuki tattoos.

"The

men and women of SRI were exploring uncharted terrain when they

began their work," said Andreas Glaeser, assistant professor

of sociology, at the November conference. Decades later, "academic

cultural analysts have finally begun to take up some of their

concerns": the use of commodities as cultural symbols, the

global impact of brand names and logos (which have become more

readily identifiable than most religious symbols), and the absolute

requirement for multi-national companies to study culture and

cultural differences.

All

this should have been apparent 50 years ago, Glaeser concluded,

in SRI's study of beer. "In the parlance of contemporary

consumption research, SRI was investigating the practices of beer

consumption while investigating the semiotics of drinking,"

Glaeser said. "SRI identified the major dimensions of the

use code of beer...teasing out, for example, the social resonance

of clinking beer glasses...and made concrete suggestions to their

clients on how to construct brand codes in accordance with use

codes, all this without using a language of identities, practices,

and semiotics, long before the academic world picked up an interest

in a related set of topics."

Not

only that, he might have added, but SRI also said it in a way

clients and consumers easily understood. "Beer," SRI

pronounced, in the parlance of people who drink the stuff, "is

not a prestige item."

![]()

BEER,

ACCORDING TO EXPERTS, "is

not a prestige item." There's nothing distinctive or exclusive

about it. Cheap and widely available, it does not require stylish,

single-task glassware, like Champagne flutes or brandy snifters,

but can be consumed from plastic mugs, recycled jelly jars, even

straight from the can or bottle.

BEER,

ACCORDING TO EXPERTS, "is

not a prestige item." There's nothing distinctive or exclusive

about it. Cheap and widely available, it does not require stylish,

single-task glassware, like Champagne flutes or brandy snifters,

but can be consumed from plastic mugs, recycled jelly jars, even

straight from the can or bottle. The

SRI team did it by applying social-science techniques to what

was then a neglected topic: why people buy stuff. The researchers

were among the first to adapt tools developed by anthropologists

for the study of primitive societies and use them to investigate

modern industrial communities. They borrowed personality tests

invented by psychologists to probe the meaning of purchasing decisions.

And they applied evolving notions of social status, mobility,

and class aspirations to understand what buying, owning, and displaying

consumer goods meant. In its short life SRI left a lasting impact

on theworld of market research, influences still felt in everything

from the absolute devotion to "brand image," to reliance

on focus groups, to academic study of the meanings of consumption.

The

SRI team did it by applying social-science techniques to what

was then a neglected topic: why people buy stuff. The researchers

were among the first to adapt tools developed by anthropologists

for the study of primitive societies and use them to investigate

modern industrial communities. They borrowed personality tests

invented by psychologists to probe the meaning of purchasing decisions.

And they applied evolving notions of social status, mobility,

and class aspirations to understand what buying, owning, and displaying

consumer goods meant. In its short life SRI left a lasting impact

on theworld of market research, influences still felt in everything

from the absolute devotion to "brand image," to reliance

on focus groups, to academic study of the meanings of consumption.