The

sacred valence: Why marriage is more than a piece of paper

>>A

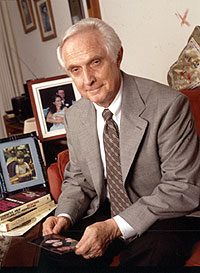

theologian caps his career with a vision for postindustrial marriage

Cuing

up a video in his shag-carpeted rec room one Monday this June,

Don Browning, DB'59, AM'62, PhD'64, invites his guests to make

themselves at home. His wife, Carol, switches off a lamp, and

the credits roll for the documentary Marriage: Just a Piece

of Paper? Browning explains to three first-time viewers that

the video is still several months from completion, at which point

it will go into the holding tanks at WTTW Chicago public television,

to be aired late this fall and, Browning hopes, nationally syndicated

early next year.

"You

wouldn't believe how much we've had to cut. This is a huge topic

to cover in less than two hours," says the Alexander Campbell

professor of ethics and the social sciences in the Divinity School

and director of the Lilly Project on Religion, Culture, and Family.

"You

wouldn't believe how much we've had to cut. This is a huge topic

to cover in less than two hours," says the Alexander Campbell

professor of ethics and the social sciences in the Divinity School

and director of the Lilly Project on Religion, Culture, and Family.

As

the music fades, journalist Cokie Roberts strolls through a sunny

garden and talks about marriage in America. Her dialogue, like

the rest of the narration, was written by Barbara Dafoe Whitehead,

AM'71, PhD'76, an expert on marriage and family issues. The same

topic has preoccupied Browning for the past decade (professionally,

that is: he and Carol, a retired church organist and piano teacher,

have been married 43 years).

The

documentary is the culmination of an interdisciplinary project

that has produced 12 scholarly books, seen countless articles

on its research appear in the national media, and received a total

of $4 million from three grants, including seed money from the

Lilly Foundation in 1991. More than 100 theologians have contributed

to the project's goal: to introduce a scholarly religious voice

into public discussions of marriage and family and to offer a

model for marriage in the future.

On

the screen, Tom Smith, PhD'80, of the National Opinion Research

Center outlines what Browning's group is up against: one-third

of married couples are divorced or divorcing; one-third of all

children are born to unmarried women; two-thirds of African-American

children are born to single mothers. The statistics from Wade

Horn, director of the National Father Initiative, are more grim:

among children not living with fathers, 40 percent haven't seen

dad in the past year, and 50 percent have never been in his house.

Other

commentators outline what they perceive to be the massive shifts

in American society that led the nation to the current situation.

The women's revolution, says Isabel Sawhill of the Brookings Institution,

opened the workplace to wives and mothers, putting an end to the

19th-century "breadwinner-homemaker" marriage model.

The sexual revolution, she continues, led to widespread nonmarital

sex; unplanned pregnancies and the now-common phenomenon of cohabitation,

she continues, were not far behind. Perhaps most profound, though,

Cokie continues, is the psychological revolution that told men

and women it's okay to seek their own individual fulfillment and

happiness, even if it means leaving behind marriage and family.

The

video's message-and the Lilly Project's, for that matter-is clear

from the start: marriage is good, divorce is not, and some force

needs to intervene and reverse the escalation of divorce and single

motherhood because it's seriously hurting the nation's children.

Browning believes the intervening force should be religion-and

religion, he is adamant, does not only mean conservative,

Christian, and right-wing. Rather, he points to mainstream and

liberal religious groups, including Catholicism and Judaism, which

contributed little to public discussions of marriage during the

late 1980s and the 1990s.

"Mainliners

and liberals accommodated modernity more rapidly than their conservative

counterparts," Browning says a few days later in his Swift

Hall office. "They're the people who go off to universities,

who are more individualistic in their point of view anyway. They

accepted divorce quite well. A decade ago sociology as a discipline

said, Don't worry about the family changes that are occurring

in our society, it just means more freedom. It wasn't until relatively

recently that social-science research has started to say that

the kids [of divorce] are suffering, that it's impoverishing single

mothers, that men are getting off the hook."

Now

more than ever, Browning believes, mainstream and liberal religious

groups must find their voices. An ordained minister of the liberal

denomination Disciples of Christ, he is addressing his peers.

In doing so, he changed the path of his scholarly career. He made

his name at the U of C studying and writing on the relation of

religious thought to the social sciences and how theological ethics

employs sociology, psychology, and the social scientific study

of religion. Of the ten books under his belt, only two focused

on the shape and future of the postmodern family. Now, as he prepares

to retire after a visiting professorship at Emory University next

year, he is glad to cap his career with a project that could have

an impact on society at large.

The

Lilly Project's approach has been quintessential Chicago, framing

a theological discussion of marriage in the context of research

from other disciplines. In the project's core book, From Culture

Wars to Common Ground: Religion and the American Family Debate

(Westminster John Knox, second edition, 2000), Browning and four

co-authors outline what they call a "psychocultural-economic"

view of marriage. On the one hand, they take into account the

work of economists like Gary Becker, AM'53, PhD'55, legal scholars

such as Richard Posner, and sociologists like Linda Waite, who

say that marriage is good because it's efficient and provides

the optimal economic, social, and psychological outcome for both

partners and their progeny. But they also acknowledge that marriage

is about something more metaphysical than cost-benefit analyses.

"Marriage

is not just about religion. Of course it's not. But it's a carrier

of religion, and religion interacts with these other benefits,"

says Browning. "It gives sacred valence to values that can

be understood in other ways. It says there are intrinsic benefits

that aren't just means to other ends." In place of the outdated

breadwinner-homemaker model, Common Ground argues for a

new "postindustrial ideal": an egalitarian family in

which husband and wife participate relatively equally in paid

work, childcare, and domestic duties.

This

may sound like Ms. magazine warmed over, but Browning points out

that his immediate audience includes theologians and religious

groups who aren't necessarily Ms. readers (though a good many

feminist theologians are on the Lilly Project roster). More to

the point, these groups haven't articulated a new "equal

regard" marriage model that also reflects the divine side

of married life. The project lays out the groundwork for them.

Browning

is quick to point out that the Lilly Project is not against the

single vocation or families that have split. "Life is rough.

There are enormous pressures in society. We recognize there will

be divorced single parents. But we're saying that people will

be able to handle these pressures better if they try to do it

better the first time. We're not out to create a stigma. But we're

also not out to accept the forces that are functioning against

lifetime marriage." The authors of Common Ground outline

the forces: a drift in Western societies toward heightened individualism;

the spread of market economics into family and private life; the

psychological shifts produced by individualism and market economics;

and the influences of a declining yet still active patriarchy.

In

the face of these challenges, Browning gives examples of trends

that support the postindustrial, equal-regard marriage ideal.

The "marriage movement" is bringing marriage education

into high schools, and many churches now require couples to attend

marriage counseling before they marry-a good sign, considering

that 70 percent of American weddings are religious. Louisiana

recently passed the first "covenant" marriage law, in

which couples agree to mandatory premarital counseling and commit

to marriage as a lifelong, sacred contract (the polar opposite,

Browning notes, of California's 1989 passage of the no-fault divorce

law, which changed the tide toward fast-and-easy divorce). And

the more the mainstream media cover research that argues for marriages

that last, the more public attitudes will begin to change.

"Is

marriage coming or going? Right now the facts point to both. Everyone's

looking for a soul mate, but no one thinks they'll find one,"

says Browning. In the decades ahead, he hopes, those who do find

soul mates will recognize that their commitment is more than just

a piece of paper.-S.A.S.

![]()

"You

wouldn't believe how much we've had to cut. This is a huge topic

to cover in less than two hours," says the Alexander Campbell

professor of ethics and the social sciences in the Divinity School

and director of the Lilly Project on Religion, Culture, and Family.

"You

wouldn't believe how much we've had to cut. This is a huge topic

to cover in less than two hours," says the Alexander Campbell

professor of ethics and the social sciences in the Divinity School

and director of the Lilly Project on Religion, Culture, and Family.