Full measure of devotion

After thrilling American readers with the tale of John Wilkes Booth’s capture, James Swanson, AB’81, continues to stoke his Lincoln obsession.

By William Wan, AB’02

Photography by Dan Dry

“Terrible News,” the headline proclaims: “President Lincoln Assassinated at Ford’s Theatre.”

The article follows with details: the assassin leapt onto the stage, ran to the wings. Just as he made his escape, the page cut off with these ominous words: “reached the door...”

“I remember reading that sentence over and over,” says Swanson, AB’81, “and desperately wanting to know what happened.”

The curiosity stayed with him throughout his childhood and later sent him searching for other Civil War and Lincoln artifacts. It brought him to the University of Chicago with a ravenous appetite for American history. It haunted him even as he pursued careers in law and constitutional studies.

Just as curiosity turned to fascination, fascination became obsession. Finally, in 2003, drawing on four decades pursuing his passion, Swanson set out to research and write the story he was never able to finish as a boy. The resulting book, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase For Lincoln’s Killer (William Morrow, 2006), sparked a publisher’s bidding war and became one of the most popular Lincoln books of all time, spending more than three months on the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list and sending Hollywood knocking on Swanson’s door.

Even now, with the acclaim Manhunt has received and the February 2009 publication of a Scholastic Press young-adult version, Chasing Lincoln’s Killer, Swanson continues to delve into the world of Lincoln, with another book due out this fall.

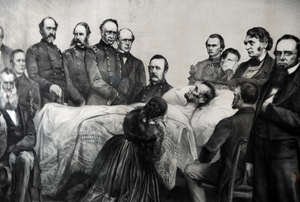

A rare lithograph depicting the boardinghouse room where Lincoln died.

“I can’t really explain it,” he says. “I guess that’s what makes it an obsession. I could give you all the rational explanations, why certain topics move me, seize me, but on some level it’s irrational. We often can’t explain the things most important to us.”

Fate seems to have brought Lincoln into Swanson's life. Swanson was born February 12, 1959—150 years to the day after Lincoln’s birth. As a child on Chicago’s Northwest Side, he received gifts from his parents and grandparents of Civil War–era kitsch and collectibles. He had coloring books, comics, and biographies written for children. His parents took him to Gettysburg and bought him a Civil War cavalry sword. They drove him to the Chicago Historical Society to see the bed in which Lincoln died.

His entire family shared a love of history. Swanson’s grandfather had been a policeman since Al Capone’s time, and he loved to tell stories from his Prohibition days through the 1960s protests. His grandmother had done clerical work for two Chicago tabloids and seemed like a character straight out of the Broadway and film comedy The Front Page. It was she who gave Swanson a drawing of the gun that killed Lincoln, framed along with that initial Chicago Tribune story he would later read over and over in his room.

So Swanson began his collection of Lincoln memorabilia early in life. He made his first major acquisition as a sophomore in high school: a wanted poster offering $100,000 for Lincoln’s killer and accomplices. He spotted it in a rare-book store and knew he had to have it. He collected the lawn-mowing money he had been saving to buy a car and used it to buy the sign.

“That poster remains one of the ultimate relics for me,” he says during an interview at Washington, DC’s Newseum, where it and other items from his private collection are on loan for a special exhibit through May 31. “Nothing quite evokes the shock, horror, and panic of what happened. An assassin on the loose. No one knows where he is.”

A photo of Booth issued to a searcher, who defaced it.

Shortly after buying the poster, he gave up going to his high-school prom so he could save a few hundred dollars toward his next Lincoln-era acquisition: an autographed photo of General Ulysses S. Grant.

As a collector, he notes, he learned quickly what his priorities were. “It takes ingenuity and sacrifice,” he says. “I never spent much on the latest cars, the most extravagant vacations, or luxuries in life. … It’s not enough to have the obsession; you need to have the patience, persistence, and knowledge to look over a long period to collect great things.”

Among his biggest finds were a playbill for Our American Cousin, the play Lincoln attended at Ford’s Theatre the night he was shot, and a bloodstained swatch of the dress actress Laura Keene wore while cradling the dying Lincoln’s head in her lap.

The greatest item of all, however, took Swanson the longest to secure: a lock of Lincoln’s hair, clipped the morning he died and given by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to one of Mary Lincoln’s few friends in Washington.

Fewer than a dozen such locks are known to exist, Swanson says, and for three decades he tracked them all until, five years ago, he acquired one from a private collector, a rare-book dealer on the East Coast. “Its value comes from the instant feelings it evokes,” he says. “Just looking at it takes me back with lightning speed to the deathbed. Everything in that room suddenly comes to life, and you see it happening right in front of you.”

From his childhood hobby, Swanson began to study history as an academic pursuit at Chicago. It was the only college he applied to. One reason was his admiration for the late historian John Hope Franklin, a seminal figure responsible in large part for introducing the African American experience into mainstream academia.

Swanson had read all of Franklin’s books, and at Chicago he took all of his classes. And Franklin, as he did for many young scholars, became a fast mentor. “He talked to me not just about history and studies,” Swanson says. “He gave me advice about women, who to date and why. He advised me on life. We had a lot of laughs together. That’s how I remember him, always laughing.”

Franklin pushed Swanson to expand upon his Lincoln interest. You can’t just study Lincoln, Franklin told him. You have to study the context—slavery, the war, all the things that made up Lincoln’s world.

In his Burton-Judson dorm room, studying late into the night, Swanson developed a relentless work ethic. That drive propelled him through law school at UCLA and stayed with him through a career in conservative Washington politics.

During the Reagan administration he worked at the U.S. Court of Appeals and U.S. Department of Justice, where he served on the team that toiled for months, unsuccessfully, to confirm Judge Robert Bork, AB’48, JD’53, to the Supreme Court.

Wrist irons were worn by the conspirators from their arrest to their execution.

Two decades later, from 2003 through 2006, he returned to a lifestyle of intense research and seclusion as he wrote Manhunt. By day he edited Cato Supreme Court Review, an annual journal for the libertarian think tank, and by night he labored into the wee hours on his book.

He wrote most of it in deliberate isolation from the modern world. He had no TV at his Capitol Hill home, which became overrun with documents and research. Rooms were piled with stacks of books. He blasted Civil War–era music as he wrote and ventured out mostly to visit settings for the book’s scenes—the house across from Ford’s Theatre where Lincoln died, the route Booth took to escape into southern Maryland, the farm where the assassin was finally cornered.

His 16-foot dining-room table, where he wrote, was swamped with sheaf after sheaf of newspapers. He had purchased a full run of Chicago Tribunes from April through July 1865, including an original copy of that first collectible story. He spread those papers across the table and pored over them, soaking in the context for the chase of John Wilkes Booth.

The intensity of Swanson’s writing surprised even his friends. Lewis Shepherd, the best man at Swanson’s wedding, recalls how he mysteriously disappeared for long stretches of time while writing, practically imprisoning himself in his house, only to emerge weeks later to throw a fabulous soirée attended by Supreme Court justices, politicos from both sides of the aisle, and authors. And once the party ended, Swanson would disappear again for several more weeks. “He still works now the way we all used to in college,” Shepherd laughs, “furiously writing and working up to the very last possible deadline.”

The Lincoln collection that Swanson had painstakingly created over decades became a boon to his writing. With all the books and primary documents he had acquired, he had an unrivaled library to draw from, 24 hours a day. Whenever he felt his writing start to wane, he would take out his favorite relics and transport himself anew to the scene of the crime. “The artifacts are like talismans to me,” he explains. “If I touch them, study them, they take me back in time, and I can see it all so vividly.”

His goal was to do the same for readers, to put others in the room as Lincoln’s life drained away, to put them in the saddle with Booth as he fled into the Maryland swamps and let them experience the urgency of authorities trying to bring justice to Lincoln’s killer.

The trick was to write suspense into a story to which everyone already knew the ending. “It’s like the Titanic. When you look back at history, it all seems inevitable. That’s how many history books are written. But when you begin to study it more deeply, you see that nothing had to happen the way it did,” Swanson says. “As a writer you need to persuade the reader to see that as well, to live the moment as the people back then did. They didn’t learn the story out of order. They didn’t know what would happen next.”

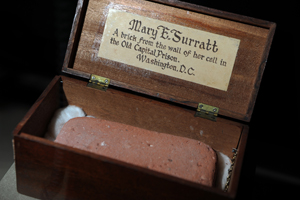

A brick thought to be from Booth coconspirator Mary Surratt’s prison cell.

As Swanson delved into Booth’s life and mind, he guarded against familiarity breeding admiration. “While I’ve come to know Booth very well, I don’t like him. He was a racist and a murderer, and he killed the man who was our greatest president. I didn’t want readers to think Booth was the hero of my book. Lincoln is the hero. But I did want readers to accompany Booth during those 12 days, as he was hunted down, cornered, and trapped.”

The result of Swanson’s labor hit a sweet spot with the American public: a high-brow interest in the details of history, a low-brow attraction to the gruesome details of celebrity murder, and a love for a well-crafted, page-turning narrative.

Even before Swanson finished writing Manhunt in 2005, his proposal’s thriller pace and marketable story sparked a bidding war among publishers. The book also made waves among Lincoln historians. Swanson, previously known mostly as a collector, came to be seen as a serious Lincoln writer as well.

“It was his skillful execution of narrative history that caught people’s attention,” says James McPherson, a dean among Civil War historians and a Pulitzer Prize–winning history professor emeritus at Princeton University. “It didn’t necessarily fit into the mainstream of Lincoln scholarship; there wasn’t necessarily groundbreaking scholarship in the book. But he used very thorough research to produce a terrific narrative. He’s somebody who can just capture the drama of history.”

Equal parts history and thriller, Manhunt attracted Hollywood interest as well. Chronicles of Narnia producer Walden Media optioned the rights. The film deal has morphed into an HBO miniseries to be produced by David Simon, writer and creator of the HBO series The Wire.

In the months and years after the publication of Manhunt, Swanson still wrestled with parts of the Lincoln story he hadn’t been able to fit into the book. Swanson fixated, for instance, on the elaborate and symbolic funeral train that carried Lincoln back to Springfield, Illinois.

Along that train ride, Swanson came to believe, as hundreds of thousands of people flocked to all the stops, Lincoln became America’s first secular saint. “Before the assassination, you have to remember, Lincoln was not universally loved. He had enemies, many critics,” Swanson says. “But on that train, Lincoln came to represent, for so many in the country, every fallen son, every lost lover from the war. All of them, in a sense, were coming home with him on that train. That’s why you saw such emotion on display.”

Swanson also became captivated by Jefferson Davis, president of the fallen Confederacy of the South. As the train brought Lincoln’s body home, Davis was already on a journey of his own, fleeing Union forces. “I had enough material between the two of them for two separate books,” Swanson says. “But I realized what fascinated me about both was their character. … Just as Lincoln’s journey made him into America’s first secular saint, Davis’s journey made him into a living symbol of the lost cause, of all the Southern dreams that never came to be.”

Lincoln mourners wore ribbons or badges on their clothing.

Swanson, who had not seriously studied Davis before, came across accounts of women dressed in black collapsing at Davis’s feet. He read of old Confederate veterans who laid their hands on Davis and experienced paroxysms. He saw similarities and stark differences between Lincoln and Davis that made each stand out sharper under the backward gaze of history.

His research formed the nucleus of his forthcoming book, Bloody Crimes: The Chase for Jefferson Davis and the Death Pageant for Lincoln’s Corpse (William Morrow). Swanson’s home once more became overrun with papers and books. He spent much of the past year in the throes of writing, again splitting his time between the book and his day job—now as a senior legal scholar at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank he joined in 2004.

With Bloody Crimes due out this fall, Swanson has several other projects lined up: the Manhunt HBO series; a possible film on Jefferson Davis; his first attempt at fiction, a thriller novel; and, according to the Washington Post, a potential Showtime series, produced by Kevin Bacon, about the Booth family’s life as actors in the 19th-century theater.

Screenwriting, Swanson confesses, is a challenge he’s particularly eager to try. And there are dozens of other topics to explore. One of his earliest writing credits, after all, was coauthoring the 1996 best-seller Bettie Page: Life of a Pin-up Legend, a distinction rarely mentioned in his think-tank bios. “It’s not just Lincoln all the time,” he says. “There are other books out there I want to write as well—the colonization of America in the early 1500s and 1600s, World War I, Lyndon Johnson, African American history.”

Yet even after the books and a lifetime in pursuit of Lincoln, the obsession still burns deep. “It’s something I think I’ll always be interested in,” he says. “He was the most literary, most well-written president we had. He was a principled man who knew that slavery was wrong. And beyond all that he had that X factor that all great men in history have. It’s a miracle that can’t be explained.

“To my mind,” Swanson says, “he was the greatest American who ever lived.”