Raised from the ruins

After looting in Iraq damaged invaluable antiquities, archaeologists work to restore the cradle of civilizationís cultural heritage.

By Ruth E. Kott, AM’07

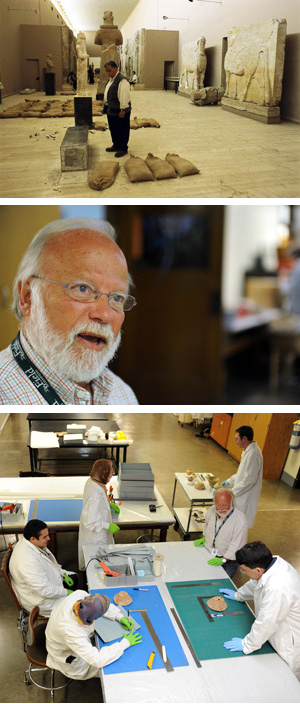

Donny George worked to recover looted items. Seven years later, Field museum curator James Phillips leads a program for Iraqi archaeologists, who learn, for instance, new methods of conservation. (Dan Dry; Steve McCurry/Magnum Photos)

On April 13, 2003, Donny George Youkhanna walked into the Iraq Museum. It was George’s first visit since fleeing the museum five days earlier, when the U.S. Army had entered Baghdad. Iraqi looters had broken down the museum’s doors and smashed windows to get in, dragging out gold, clay, and bronze pieces, and even stripping the museum of electrical wire and office chairs. Staircases were chipped as the looters heaved large antiquities from upper floors. United States military tanks had sat outside the museum, making no moves to stop the pillaging. In George’s short absence, some 15,000 artifacts were stolen.

Having watched the destruction unfold on TV, George (as he’s known in the West), then director of Iraqi museums, was braced for the damage. But he didn’t expect the loss of one particular artifact: a 600-pound alabaster vessel known as the Warka Vase. Named for the village where it was excavated in the 1930s, the vase, a relic of the long-buried southern city of Uruk, is carved with scenes that, scholars believe, depict the ancient Sumerians’ daily life and guiding beliefs. Dated to 3200 BC, it is among the earliest sculptures from the first-known civilization, carved around the time the Sumerians invented writing. “The lower panel starts with water, then plants, then animals,” George explains. Humans populate the center panel, and at the top sits the deity, most likely the goddess Innana. The vase is an icon of Mesopotamian art. “It’s a beautiful work that summarizes the great philosophy that the Sumerians had, in just one piece of art.”

When he entered the museum that April afternoon, he saw the vase’s stand lying on the floor, its glass display case shattered. The vessel had been hacked away from its base, which still was attached to the pedestal. “I just became crazy,” says George. “I said, ‘The looters have taken it. That’s it.’ For me, losing the Warka Vase is losing the masterpiece of the Iraq Museum.”

They also took advantage of the invasion to ransack several archaeological sites, and the damage reverberated well beyond the nation’s borders. As Geoff Emberling, the University’s Oriental Institute Museum director and curator of the 2008 OI exhibit Catastrophe!, writes in an accompanying essay, “The loss of Iraq’s cultural heritage is simply a loss for humanity.”

To help the Iraqis protect their remaining archaeological record, in October 2008 the State Department launched the Iraq Cultural Heritage Project. The approximately $13 million effort will build a training institute in Erbil (the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan), help archaeologists publish excavation reports in Arabic and English, and provide the Iraq Museum with better collection and conservation tools and technologies.

In Chicago, Field Museum of Natural History curator James Phillips, AM’65, directs another segment of the project, working with Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute, to train 18 Iraqi archaeologists and conservators. Split into groups of six—the first cohort returned to Iraq this past September; the third completes its training in September 2010—the visiting Iraqis live in Hyde Park’s International House. After a month of English-language training, they spend much of the next five months at the Field Museum. Field and OI staff lead sessions and lectures about conserving metals, papers, and ceramics (how to get rid of salt encrusted on pots, for example); data management; storage; and exhibit design.

Some of the sessions take place in the Field’s Collections Resource Center, a 180,000-square-foot storage and research space for millions of pieces not on display and for new acquisitions. For one November class on textile storage, five folded cloths, each woven with rows of diamonds, lightning bolts, or colorful plant-like designs, lie on a long table. Patricia Lord, the Field’s assistant registrar of new acquisitions in anthropology, picks up a brown cloth. The six Iraqi archaeologists huddle around as she unfolds it. It’s a contemporary Mexican textile, nothing too fragile. The process “seems harder than it is,” Lord says, “but once you get the hang of it, it’s really easy.” She lists the supplies it takes to roll a single piece of cloth: “an archival tube; plain, unbleached, cotton fabric; the textile; and then clear plastic and Velcro to keep everything together. And it all just gets rolled.”

Lord calculates the width of the cloth, pulling the corners taut and smoothing the wrinkles with her hand before pulling out a measuring tape. The textile’s size determines how big a piece of muslin to cut and how big a tube to wrap it around. Once everything has been measured, the tube cut to size with a hand saw, and the muslin glued to the tube, “the hardest part,” says Lord, “is making sure [the textile] rolls straight.” Methaq (the Iraqis’ last names were withheld at the Field’s request), a 31-year-old archaeologist who works in the Iraq Museum’s database department, comments that the exercise feels somewhat familiar; in Iraq she rolls her carpets after the winter to store them.

When finished, Lord writes the identification number inside the tube and on the plastic wrapping with a Sharpie and stores the piece on a shelf behind them. Opened in 2005, the climate-controlled storage space holds more than 2,700 sections of shelving made to support items of any weight.

“Here the museums are so modern,” says Methaq. “The shelves here are not like the shelves in Iraq.” There they wobble, she says, like they’re going to break—“so old.”

The Iraq Museum also lacks the Field’s space. “We try to make some space in the storage,” says Methaq’s colleague Ali, but it soon gets filled by new artifacts, including looted items returned to the museum. “So we store them again on the ground, which is not a very healthy environment for many pieces.” Iraq Museum archaeologists are so cramped for research space that they worry about damaging the pieces they try to analyze, which are often surrounded by other artifacts. Says Ali, “You’re trying to be very careful of the other objects to prevent harm.”

The Assyrian stone relief was too large to be stolen from the Iraq Museum. At the Field, J. P. Brown works with an Iraqi. The museum has the largest collection of pieces from a single Mesopotamian site. (Dan Dry; Thorne Anderson/Corbis)

The museum’s contents were initially disturbed during the first Gulf War, which started in August 1990 and lasted seven months. The Iraq Museum is the country’s umbrella archaeological institution, overseeing the 13 provincial museums, and by war’s end—when thousands of items had been looted from nine regional museums—the country’s collection was in disarray. Before then, says McGuire Gibson, AM’64, PhD’68, professor in the Oriental Institute and Near Eastern languages and civilizations, “if you asked for an object, they could go and get it for you, or they could come back and say, ‘No, it’s on exhibit in Mosul,’ or, ‘No, it’s on exhibit upstairs; go look at it,’ or, ‘You can’t look at it right now.’ You’d ask for 20 things, and you’d get 15 things in a tray that they could find immediately, or within 20 minutes you’d find everything. The procedures they had were very good ones.” But during the war, “a lot of stuff was stolen,” says Gibson. “A lot of stuff was just broken.”

In 1992 Gibson, then president of the American Association for Research in Baghdad, and Augusta McMahon, AM’86, PhD’93, now a University of Cambridge senior lecturer in anthropology, published Lost Heritage: Antiquities Stolen from Iraq’s Regional Museums, cataloging 200 items, with descriptions and photographs when available, says Gibson, “so that in case these particular things showed up, people would know they were stolen.”

Recalling the damage done during the first Gulf War, as the United States planned to invade Iraq again in 2003, Gibson worried about looting. Iraqi law forbids the export of antiquities found there, but smuggling is lucrative. Two decades of war and UN sanctions had left Iraqis impoverished. Throughout the 1990s the underground antiquities market escalated, fueled by increasing demand from collectors, enriching dealers who in turn paid the looters. “I know for certain,” says Gibson, that some of the stolen pieces “are in private collections around the world.”

Gibson also knew that protecting museums was only part of the story. During the 1990s, when the United States declared no-fly zones in northern and southern Iraq, the Iraqi government couldn’t use helicopters to survey archaeological sites, so security waned, especially in the south. Sites were wide open. Illegal digging operations unearthed cylinder seals—intricately decorated stones used to roll an impression into clay—which were in high demand because they could draw hundreds of thousands of dollars. About the size of a finger, the seals are easily portable, so looters had a good chance of selling them to antiquities dealers, writes Lawrence Rothfield, cofounder of the University’s Cultural Policy Center, in his 2009 book The Rape of Mesopotamia: Behind the Looting of the Iraq Museum (University of Chicago Press).

Nor was anyone on the ground guarding the sites. Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage budget had been cut down to about $2 million, writes Rothfield, an associate professor of English. That figure could barely pay the limited staff regularly, much less provide them with vehicles to reach the sites they were meant to protect.

With so few guards, the chance for wartime looting was high, Gibson warned American officials during the pre-war planning period. In early 2003 he provided the Defense Department with the coordinates of some 4,000 important archaeological sites, urging the military to avoid bombing the sites or using them as bases: “Armies always take high ground,” says Gibson, “and the sites in Iraq are high ground. These are mounds.” In the months before the April attack, “I was getting these calls from these young guys, sergeants and lieutenants in the Defense Department, who were calling me to check on the location of this place or that place.” They had more accurate equipment and satellites than he did, so Gibson figured they were correcting the locations he’d provided. “I’m assuming all this stuff is going into the Army’s computers, and everybody’s going to know where these things are.”

He was wrong—the Army never saw that list. In 2008 Gibson learned that it had been immediately classified as top secret, kept only within the Defense Department. Rather than calculating the exact location of Nippur, for example, those callers “were just the guys who made the maps,” says Gibson. They had no say in whether or not the sites were protected. “They were just putting stuff on maps and saying, ‘This is not a target. This is not a modern, man-made thing which might have a tank hidden under it. This is an ancient site.’” On a post-invasion trip to Iraq that May, he saw that some sites had been protected—mostly out of luck, he thinks, because many of the soldiers thought they were nothing more than hills. He got messages from soldiers, Gibson recalls, that said, “I was in this hill, and we dug into it, and things were coming out. There are things in these hills.”

Of all the sites on his warning list, Gibson emphasized the Iraq Museum the most. But the chilling images of toppled display cases, chipped ceramics, and trashed storerooms showed that his warnings had been in vain. Gibson had assumed that the museum would be secured as soon as soldiers were in the neighborhood, he told the Chicago Tribune in 2003. But after the invasion, when generals were asking him for the museum’s coordinates, doubt settled in.

Donny George also assumed the museum would be protected. With three other colleagues, including then–State Board of Antiquities and Heritage director Jabir Khalil Ibrahim, George stayed at the museum when the U.S. military entered Baghdad. The staff had a tried-and-true method for protecting the antiquities: First the employees “evacuated all the small items from the showcases. Only the large pieces were left, and they were covered in cushions. Sandbags were put on the floor around them so that if they fell down, they would not be hurt,” says George. “This was the only protection we had. The museum police just went away.” The Warka Vase, like other large sculptures, was not moved for safekeeping; the evacuators thought no looters would attempt to move the heavy, nearly four-foot-tall object.

Site looting is still a major problem, and artifacts end up on the black market. The fieldís collection includes only objects obtained legally. (Luke Baker/Reuters/Corbis)

On April 8, Iraqi civilians, armed with rocket-propelled grenades and Kalashnikovs, entered the museum grounds, aiming at American tanks. Afraid of being caught in the crossfire, George and his colleagues left the museum and took cover in a government building across the Tigris. When they tried to return that afternoon, they were stopped and told that American forces were controlling the area. They turned back, George says. “But I was relieved. I said, ‘OK, they are controlling everything. They know for sure that this is the museum, and they will protect it.’”

The looting began two days later, but it was April 12 before George learned about it on the BBC evening news. The next day he went to the museum and found no troops guarding it, only staff members armed with clubs. He walked inside and surveyed the damage. “My heart was bleeding,” he says. “I excavated a lot of things there.” After working there for almost 30 years, “I knew every single piece in every single hall in that institution.”

On April 16, U.S. troops finally secured the building. Worldwide efforts to recover the items began immediately. The Oriental Institute started the Iraq Museum Database Project, led by Clemens Reichel, AM’94, PhD’01. Just as Gibson had during the ’90s, Reichel, now an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, made a list of as many missing artifacts as possible and put it online. “He posted that stuff just so, in case it showed up on the market, people would know,” says Gibson, who doubts that pieces such as the Warka Vase would have shown up there. “I will bet you that the guys who stole that went to a dealer and said, ‘We’ve got this—you want to buy it?’ And the guy said, ‘Don’t even try.’ It’s just too hot to handle.”

In Iraq, George launched an amnesty program that also offered cash rewards to people who returned looted items. Although his team had no budget in the first two years, by 2005 they were able to make payments retroactively. Others joined George’s efforts to find lost antiquities: U.S. Marine Colonel Matthew Bogdanos received the 2005 National Humanities Medal for his recovery work. Local police helped track objects circulating in Iraq. Interpol and UNESCO intercepted pieces smuggled abroad. According to current director general of Iraqi museums Amira Edan, about 5,000–6,000 antiquities have been returned.

But the pillaging of archaeological sites continued. In 2005 George formed an antiquities police unit. “In Iraq we have special police for the electricity system, the high-tension towers. We have special police for the railroads. We have special police for the oil installations.” The minister of culture agreed to George’s idea of an antiquities force. George received a budget for salaries and weapons and recruited 1,400 former police and military members, and local tribesmen. With help from the United States and Japan, he got them cars, and UNESCO sent wireless communications systems. “Little by little,” says George, “they became very effective. In any province that they had complete equipment, they did an excellent job.”

The special police slowed looting for about a year, when the money started disappearing. “First the budget for gas for their cars was cut,” says George. “Then the budget for their salaries was cut.” Around that time, in August 2006, he fled the country after he and his family received death threats. The force eked out some financing for a little while, but George learned in January 2008 that a government order had required the antiquities police to return to the regular policing system. “Imagine,” says George, who now lives in New York, teaching at SUNY–Stony Brook: “They were all recruited to protect the sites; now they were ordered not to protect the archaeological sites. The sites are left alone now, and no one is patrolling them.”

Some of these sites cover hundreds of acres. Without armed guards, the looters easily gain the upper hand—they have weapons and are prepared to fight. They often work at night, says Gibson, “because it’s too hot in the daytime.” Some thieves build tunnels and trenches, while others simply use bulldozers.

When a site gets ransacked by nonexperts who don’t properly dig or document, a part of the mound’s history becomes lost. The Oriental Institute’s Stein calls studying looted sites an “exercise in frustration”: “It would be like trying to excavate spaces between holes of Swiss cheese and connecting the dots.” An artifact pulled from the ground without noting its location and surroundings offers no clues to its cultural significance. In an essay accompanying the OI exhibit Catastrophe!, PhD student Katharyn Hanson, AM’06, argues that “a looted artifact sold on the art market can stand alone as a pretty piece of artwork, yet without archaeological context this pretty object simply represents lost knowledge.”

Although the difference between a pretty object and a piece for scholarly analysis lies in its documentation, the scientific process of recording excavations has been somewhat lost in Iraq. “The older generation of Iraqis who would be teaching these people,” says Gibson, “so many of them have left, or they’re working in other countries, or they’ve retired.” Once strong, the university system has been “on hold” since 1991, he says, because of the economic embargo imposed by the UN Security Council. Some archaeologists can leave the country to take conservation or Geographic Information System courses, but Gibson hopes to bring Iraqis “out to American and other foreign digs in surrounding countries so that they can have some experience working with very, very good teams.”

The Field Museum/Oriental Institute program for the Iraqi archaeologists helps them become self-sustaining. Four Iraqis from the winter group work in Baghdad, another works in the Babylon Museum, and the sixth in Kurdistan’s Sulameniyah Museum. Nearly everything they learn is new to them—accepted practices in the museum world and why they’re important. The Field has one of the largest collections of Mesopotamian archaeology from a single site, Kish, so the Iraqis work on material from their own country.

A session led by Field Museum conservator J. P. Brown, SM’05, for example, teaches them to control relative humidity for minimizing damage to objects in storage or on display. Sitting around a table outside program director James Phillips’s office, surrounded by display cases of prehistoric human bones, the archaeologists predict changes in relative humidity using a psychrometric chart, a tool for conservators to determine how much the air is saturated with water vapor. “If you make the air too cool,” Brown tells them, “humidity will increase, and that can be bad. If the humidity goes above” a certain level, “there will be mold growth” on an object, and chemical-deterioration processes, such as metal corrosion, will increase dramatically. If the humidity goes too low, on the other hand, organic objects such as paper can embrittle, shrink, and crack. The Iraqis trace their fingers over the graph, working in pairs, while Brown looks over their shoulders and answers questions. He provides alternatives to air-conditioning, which is expensive to maintain and often unnecessary, even in extreme climates like Iraq. Climate-controlled display cases, for example, maintain appropriate conditions around objects at a fraction of the cost of full-building air-conditioning.

After being looted in April 2003 despite U.S. tanks stationed directly outside, the Iraq museum was left in shambles. (Joanne Farchakh-Bajjaly; Patrick Robert/Corbis)

Training archaeologists is only one part of digging Iraq out of a mess created by war, sanctions, and looting. The Cultural Policy Center’s Rothfield calls on Western universities to develop cultural-heritage policy research. The center, originally formed to support the arts and domestic-policy issues, has since 2003 adopted protecting archaeological sites as a cause. The effort takes not only understanding international antiquities laws, says Rothfield, but also familiarity with the U.S. military’s war-planning policies and the State Department’s nation-building policies. The 1954 Hague Convention, the only international protocol to address protecting cultural heritage during wartime, doesn’t require an invading military to stop civilians from looting. And the United States didn’t even ratify the convention until September 2008. Before then the Army’s field manual—the Pentagon’s “bible for invasion planning,” says Rothfield—didn’t have a single sentence about securing museums and cultural sites. In 2008, after the publication of his edited volume Antiquities Under Siege: Cultural Heritage Protection After the Iraq War (AltaMira Press), the provision was added. Copies of the book sit in the State Department office in Baghdad, says Rothfield. “That’s a huge step forward for future invasions.”

Legislation to curb the black market is also needed, says Donny George. The United States permits imported antiquities if the owner has papers to back them up. But because Iraqi law has prevented exporting artifacts since 1936, George says, “the majority of the papers the dealers have for the antiquities are fake.” Until the United States obstructs the underground market by rewriting lax laws that encourage smuggling, George suggests, looters will continue to dig.

Large-scale site looting, writes SUNY–Stony Brook professor Elizabeth Stone, PhD’79, in the Catastrophe! catalog, is caused by “a breakdown of local law and order” combined with poverty. Gibson believes that economic support and a stronger Iraqi Department of Antiquities—backed up with military force—would stop the pillaging. “In the ’70s, in about a three-year period,” says Gibson, the Iraqis “built an incredible infrastructure”: new roads, airports, schools, and hospitals all over the country. “They could do it again if they had the management to do it.”

Once security has been restored, scholars will dig there again, George believes, even with the damage done. “They can have hundreds of expeditions working for at least two, 300 years to come, to learn more and more,” he says. “When everything has settled down,” Mesopotamian archaeologists from all over the world “should work together to find out a special way of dealing with the looted sites: how to recover things, how to go back and find some special techniques to bring to life what has been damaged there, to fill in the empty spaces and document what’s there.”

Both George and Gibson hope to return to Iraq some day. “I would love to go back,” says Gibson. “I would love to be digging. But the problem is, you can’t guarantee the safety of your crew. … You can’t put other people’s lives in jeopardy.”

When George returns, he can visit the Warka Vase. Three men brought it back to the museum in June 2003, unprompted. Stowed in the trunk of an old red Toyota, the vase was handed over in pieces, much as it looked in the 1930s when German excavators found it, broken into one large section and about six smaller ones. Archaeologists restored the vessel then, and Iraqi conservators have repaired it again.

Although the vase is one of the most important artifacts in Mesopotamian archaeology, for George, “every single piece is very precious.” Every object holds a key to unlocking the stories of the Sumerians or the Akkadians or the Babylonians, to understanding how the earliest civilizations lived and died. “Losing any piece is a great loss,” says George. “Having any piece back is a great joy.”