Treasure trove

Herb Kawainui Kane celebrates more than 50 years of painting Hawaii-inspired art.

By Susan G. Hauser, AM’75

Photography courtesyHerb Kawainui Kane

In 1984 Herb Kawainui Kane, AM’53, was declared a Living Treasure of Hawaii, an honor awarded annually to Hawaii residents who’ve made major contributions to the state. Not bad for a guy who grew up in Wisconsin and studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago in a joint program with the University of Chicago.

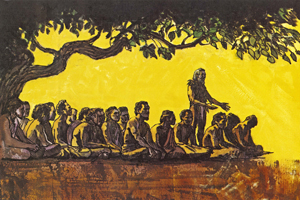

Kane’s 1975 painting Armistice helps tell the story of the first Hawaiians, more than 1,500 years ago.

Kane’s vivid oil paintings of scenes from the state’s history are almost as recognizable to Hawaiians as palm trees. His paintings grace many a museum wall and hotel lobby, and his art has appeared on seven U.S. Postal Service stamps—including the 2009 Hawaii commemorative stamp celebrating 50 years of statehood. Now, at age 82, Kane (pronounced Kah-nay) is working on a nine-foot-long mural for Honolulu’s Royal Hawaiian Hotel that depicts Kamehameha the Great’s 1795 invasion of the grand hotel’s domain, Waikiki Beach.

A resident of Hawaii since 1970, Kane stays true to history in his paintings. They depict kings wearing luxurious hats and capes made from the feathers of colorful birds; fierce battles waged in lush green island valleys; and sailors steering massive canoes over rough ocean waves. “I’ve always believed in doing the best scholarship one can,” says Kane. “When an artist researches history, he’s bound to get different views than views taken by historians.”

His interest in Hawaii started young. As a Midwestern schoolboy Kane was enchanted by his Hawaiian father’s stories. He learned about the Polynesian voyagers who crossed the Pacific Ocean in canoes nearly 2,000 years ago to settle the sunny islands. His favorite historical figure was Kamehameha the Great, who by 1810 had united all the islands under his rule.

He found later that he wasn’t alone in his pursuit to learn more about Hawaii: his 1970 move to the islands coincided with the beginning of the Hawaiian Renaissance, a movement that helped to rescue the state’s nearly extinct language and save crafts and customs that were in jeopardy of slipping forever into hazy memory. Residents in the early 20th century were influenced by straitlaced 19th-century American missionaries who had attempted to erase what they considered the natives’ heathen lifestyle. Kane’s paintings, numbering almost 500, helped to revive a long dormant interest in the culture. Kane, now considered a father of the Hawaiian Renaissance, and his paintings satisfied Hawaiians’ hunger for self-knowledge.

It wasn’t only his paintings that sparked a renaissance—it was also his work reviving traditional Polynesian ocean navigation and canoes. While studying at Chicago, he spent a lot of time in the Harper and Field Museum libraries, researching ancient canoes. Starting in 1955, he painted a series of 14 vessels, based on his scholarly and personal research.

After the director of the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, who was impressed by the canoe paintings, flew to Chicago to purchase them, Kane realized he wanted to do more to satisfy his fascination. In the early ’70s, he designed and helped to build a 60-foot replica of the double-hulled voyaging canoes that ancient Polynesian explorers sailed to the Hawaiian Islands. Kane named the canoe Hokule’a, the Hawaiian name for the star Arcturus, which guided those early Polynesian sailors.

Kane first learned to sail on Lake Michigan. In 1963, while working as a graphic artist in Chicago, he bought a racing catamaran to get a feel for what Polynesian explorers experienced. “Lake Michigan is a very good place to learn how to sail,” says Kane, who lives in South Kona, Hawaii, with his wife, Deon. “I spent a lot of time there, more than I should have.”

He captained the Hokule’a’s “shakedown cruise,” and the vessel has made many ocean voyages since 1976, with crews trained in traditional star-based navigation. “The result,” says Kane, “has been a Pacific-wide revival of interest in canoes and voyaging. There’s an international canoe regatta every other year in Fiji,” and Kane contributed to the design of those ships. In 2012 the Hokule’a is scheduled to make a round-the-world cruise, but Kane doesn’t sail anymore. “I’ve lost my sense of balance, which is very important in sailing.”

Beyond the canoes, his work has reached an audience outside of Hawaii: in 2008 the Art Institute of Chicago awarded Kane an honorary fine-arts doctorate. About a year later, in April 2009, he started sharing his paintings and his stories about the early Hawaiians with a global audience, thanks to what he calls his Online Retrospective (herbkane.wordpress.com). He e-mails a painting of the week to a mailing list numbering about 700.

With his art, he continues the tradition of his father’s storytelling but finds he’s always learning more. New views and ideas, like those sparked by his work on Polynesian canoes, have become apparent to him through his art, he says. “It comes from having an inquisitive state of mind.