Stick to the script

Anthropologist and SSA professor E. Summerson Carr parses addiction therapy’s linguistic rituals.

By Lydialyle Gibson

Illustration by Guido Mendez

E. Summerson Carr first arrived at Fresh Beginnings, a drug-treatment program for homeless women, as a social worker in training. It was the late 1990s, and Carr was finishing up a master’s in social work at the University of Michigan. Fresh Beginnings (a pseudonym she gave to the intensive outpatient drug-treatment agency, located in an unnamed, economically troubled Midwestern city) was her field placement.

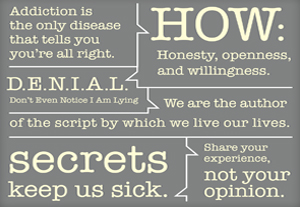

Before long, Carr found herself becoming as much a linguistic anthropologist as a social worker. Now a School of Social Service Administration assistant professor, she noticed the carefully prescribed language that governed addiction treatment’s “therapeutic rituals”: the idioms and ideas that social workers and recovering addicts use to talk to each other, a vernacular rooted in the conviction that addicts are in denial about their disease and therefore incapable of expressing what their therapists regard as their “true inner selves.” Carr notes some of the slogans that were in frequent use there: “secrets keep us sick,” “honesty, openness, willingness,” “share your experience, not your opinion.” The women were often told to “take inventory” of their lives, to “reach deep inside and find inner truths” there. On the wall at the facility hung a sign: “DENIAL: Don’t Even Notice I Am Lying.” This way of characterizing language can turn client and therapist into adversaries.

Carr’s interest in language began with her first social-work assignment. Fresh Beginnings’s funding required the agency to include clients in program governance, and Carr’s job was to help find ways to make that happen. “Yet when the rubber hit the road,” she says, “it was very difficult for them to figure out how to do that.” Therapists balked at clients taking part in program oversight. “I became completely fascinated with the rationales the professionals used to say no. Things like, ‘To what degree can we count on these women to act as representatives?’ In clinical terms, that means, ‘Can they represent their true selves, considering that they’re in denial? Can we really rely on what they say, because they’re addicts?’” After her master’s degree, Carr embarked on a PhD in anthropology and social work, also from Michigan, for which the bulk of her research was a three-and-a-half-year study of interactions among clients and therapists at Fresh Beginnings. She attended group therapy sessions and advisory board meetings; she spent hours sitting on the front porch, where clients gathered to chat and complain and share stories. She interviewed therapists and clients at length, taking oral histories from both.

Carr’s research became the basis for Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety (Princeton University Press, 2010), a book that examines the effects of addiction therapy’s codified language and how that language reflects broader American cultural values. “The idea, for instance, that a healthy, normal, good, morally worthy person is someone who speaks inner truths,” Carr explains. “That, when you speak, the less mediated your voice is by social factors—for example, what you think someone wants to hear, or what kind of institutional environment you’re in—the better, the healthier you are. In the United States—and not just in drug-treatment settings—the sobriety of the person is measured by the sobriety with which he or she speaks.”

One phenomenon Carr discovered was a practice called “flipping the script,” which the women—both those who were still using drugs and those who weren’t—used when talking to their therapists about their addictions and recovery. “Basically, it’s telling people what they want to hear,” Carr says, which isn’t necessarily the same as telling a lie. “People do things with language all the time that fall out of those two categories of truth and its denial: using language performatively or as a way to cajole or persuade.” Usually, flipping the script involved weaving real details from clients’ lives into a narrative that would convince their therapists that they were no longer in denial about their addictions, or that they were staying sober, or that they were following Fresh Beginnings’s rules.

Shaping these narratives took skill and practice, and the clients who were the most successful at flipping the script weren’t necessarily the ones who were using drugs, Carr says. “If addiction is considered a disease of insight, and you’ve been cast as a person who has lived in denial, that sets up the interaction so that you’re always trying to convince your therapist that you’re being truthful to them and yourself. Therapists were not going to believe you unless you made them believe you.”

For the women at Fresh Beginnings, flipping the script was a high-stakes venture; their therapists’ written evaluations could affect whether their children would be taken away or if they would be eligible for welfare benefits. Therapists’ evaluations could keep them out of jail or keep them locked in the program for a longer period. Therapists begin from the belief that addicts can’t help but be in denial, so whatever spontaneous, unscripted narratives the clients tell must be untrue. For these reasons, Carr says, clients are trying to tell therapists the truth they want to hear. In the meantime, many realities were left unspoken.

She offers an example: most of the women, she says, faced a multitude of serious problems, of which addiction was only one. They were born into poverty and endured prejudice as African Americans. Many lived in violent neighborhoods and some had little education; many were the victims of domestic violence. Some had been in trouble with the law. All of them were homeless. “So there were other factors, and drug use was one of them, but it may not have always been the causal source” of their problems, Carr says.

But in addiction therapy, clients are conditioned to conceptualize drugs as the root of their problems and to describe their lives that way. Social workers are trained to flag anything less as an act of denial. “The way clients are taught to tell stories about themselves leaves out so many of those other issues,” she says. “It’s not, ‘I suffer because I was born to an impoverished family,’ or ‘I suffer because I’m African American and deal with discrimination all the time,’ or ‘because my husband beat me.’ Those were illegitimate narratives in this place. And that worried me.”

Carr explains that the fault doesn’t lie with the therapists. “It’s not because they’re bad therapists,” she says. “They’re good therapists; they’re just operating on these cultural assumptions that we don’t generally attack. … From the therapists’ perspective these linguistic rituals were incredibly important for women to speak their inner truths—that this was going to be the way [the addicts] would recover from addiction. And they connected these rituals with life and death—they really felt like they were in a life-and-death struggle.”

Since Scripting Addiction was released in October, Carr has heard from caseworkers and social workers for whom her description of addiction therapy rang true. “They say, ‘Well, that’s why I left. I couldn’t do the work anymore.’” In the book, Carr generally avoids prescriptions for improvement, but during the past two years she’s begun a new research project that might offer some answers: she is studying a therapeutic method called “motivational interviewing.” A form of talk therapy developed in 1983 by two psychologists to help problem drinkers, motivational interviewing is now used worldwide for couples counseling, weight control, preventative medicine, and substance abuse treatment.

In this method clients tell their therapists why they want to change and acknowledge their ambivalence instead of having motivations imposed by the therapy. “It begins by abandoning the idea of denial,” Carr says. “That’s huge. It’s a sea change. I don’t know if it’s the answer, but it’s interesting.”

Return to top