Return to Magazine Home Page

Photography by Matthew Gilson

Ignorant because Sitcom is the latest arrival on the University's improvisational scene, and in improv even the cast doesn't know what's next. And blissful because this is a pack of TV junkies, and each time Sitcom hits the stage the result is a show that looks and sounds like television, complete with commercials and an upbeat theme song composed on the spot by Sitcom's two musicians. While the wave of nostalgia for the 1970s has spawned shows in Chicago like The Real Live Brady Bunch, where actors repeat the original TV scripts, the Sitcom crew never has to do a rerun.

On this particular evening, the cast was finishing up rehearsal when there was a loud knock on the door: a stranger. All you savvy situation comedy viewers out there know that a stranger at the door is a threat to the beautiful, internal logic of sitcoms. An outsider blasts the equilibrium of whatever insular crowd inhabits a show's living room, office, or island; the interloper comes in and wreaks emotional havoc on one of the characters and is ultimately driven off. This time, however, it was only a reporter from the Magazine.

When Sitcom came to the University Theater for six nights in October, it brought with it a suitcase full of academic theory. It all began with an assignment in Professor Kristian Hammond's Practicum in Artificial Intelligence class: Come up with a software program with "cocktail-party appeal." For Daniel Goldstein, a graduate student in computational psychology, the result was "Structuralist Gilligan," a computer program that can predict the outcome of a sitcom by matching its circumstances to other plots stored in its memory.

To develop the program, says Goldstein, who recalls coming home from high school to watch back-to-back episodes of Gilligan's Island, "I watched a couple hundred sitcom episodes and read the plot synopses of even more." He discerned that sitcoms follow a certain predictable trajectory-something that should surprise few people. Borrowing a page from the Russian literary critic Vladimir Propp, Goldstein plugged the elements into a structural analysis, mapping out a narrative path that moves from Initiating Event and Conflict to Action and Resolution.

Consider a Three's Company episode that begins with someone calling Janet dull, and Janet fearing that, alas, she is dull. She traipses off to a nude beach, hoping to prove herself, but instead has a bad experience. By the end of the half hour, she has learned a valuable lesson and has resolved her fear-of-dullness.

Or imagine a structured world where the arrival of the Magazine's reporter in the Reynolds Club could be compared with an episode from Gilligan's Island, and represented thus:

Harmony is restored, and cast and reporter break for a commercial.

"When you watch as much TV as I have," Goldstein says, "you start to notice regularities between the shows, and pretty soon you are predicting the jokes. And even though you are doing it, you still love it because you can predict the jokes. You are an expert."

Armed with his tidy structure and a seemingly boundless enthusiasm for sitcoms, it was inevitable that Goldstein, who performs with Off-Off Campus, the University's student improv group (with roots to Chicago's Second City and its Hyde Park predecessor, the Compass Players), would want to move from the theoretical to the applied.

On a road trip through the South, Goldstein discussed his ideas with John Bourdeaux, another Off-Off Campus performer who also happened to be hooked on sitcoms. Bourdeaux, an ebullient American history major who could perhaps be best cast opposite the academic Goldstein as the fun-loving fraternity member, was enthusiastic. Back in Chicago, the two got the go-ahead from the University Theater student committee and UT director Bill Michel, AB'92, to mount a production of what has now become Sitcom.

Goldstein and Bourdeaux talk about sitcoms with the fervor of religious zealots. You get them started and they cannot stop. They feel like they've really stumbled upon an invention as important as the sonnet or the internal combustion engine. They sound like mad scientists who have tapped into the power of the sun.

"There's something special about sitcoms," Goldstein says. "The characters and locations kind of burn their way into you, and after a while you start to think there's a person named Alex Keaton out there, or that right now Hawkeye Pierce is cracking jokes with B. J."

Bourdeaux agrees with Goldman that there's something psychologically satisfying about the closure sitcoms provide. A few minutes later, he starts absentmindedly humming the theme song from Happy Days. Confronted with this, he retorts, "Do you have any idea how many sitcoms we've watched?"

"Sitcom is ridiculous," admits Bourdeaux, "but it is a lot of fun. We don't take ourselves seriously, but if we weren't serious about improv then it could never be funny, and we could never pull it off."

The cast, recruited by Goldstein and Bourdeaux, consists of other like-minded souls. They are all quick and funny, and doing this work makes them very, very happy. When cast member Nick Green, in character as an Igor-like bell ringer at a cathedral, tells Bourdeaux the priest that "all that time I thought God was testing me with this affliction [his hump], but instead he sent you from hell to torment me," it's a line of such sitcom authenticity that they both revel in the moment. The priest, explaining the crisis of faith in his congregation, deadpans that "bingo, three-bean salad, and camping are not the pillars upon which faith is built."

Hanging around the theater after rehearsal, it's clear that they "impress the hell" out of each other, as cast member Josh Sinton puts it, and they laugh appreciatively at off-stage jokes. It's a modest group, surprisingly ego-free, probably because the University is theater-major-free. While some of the students-six men and two women-had performed with Off-Off Campus before, others had never done improvisation until they joined Sitcom.

In this group, admitting that you've watched a lot of Green Acres or Mary Tyler Moore doesn't really count as a confession. It's more likely a job requirement. Sinton describes himself as "fortunate to have retained an enormous amount of sitcom junk," and the rest of the Sitcom cast-John McCorry, Jim Ortlieb, Emily Pollock, Abby Sher, and Green-are similarly blessed.

Their background came in handy in creating the final look and feel of Sitcom. Where Goldstein's program had provided the emphasis on story structure, the rest of the details were worked out by the cast. By culling their memories and studying the shows of their childhood, now seen in constant reruns on cable television, they filled in the specifics on what makes sitcoms work. Ortlieb timed scenes with a stopwatch, Green took notes on the rhythm of jokes, and Sher noted the impact of entrances and exits. McCorry suggested that the recurring locations of a sitcom encourages the audience to think of the characters as old friends.

Then there is the primacy rule. Explains Goldstein: "If someone mentions at the beginning of the show that they haven't seen their friend that much, we know the show is going to wind up being about a friendship drifting apart, and that by the end they'll be buddies again."

Each Sitcom begins with a cheery host soliciting suggestions for the location and for two sets of relationships, which could be anything from boss/secretary to predator/prey. He or she-the cast members alternate in the role-also asks the audience for an initiating event. Two actors work as the commercial crew each evening, wigging out with giddy advertisements for "earwax," "cream cheese," "exuberant," or other words provided by the audience before the show begins (and beamed up on an overhead projector at each commercial break).

When "PC" flashes on the screen, we are treated to a 15-second promo for a "political-correctness indicator," which enables the bearer to determine the multi-ethnic background of everyone he encounters; "leather" elicits a wicked take on the man-on-the-street interview, when a hapless model can't find anybody to admire his jacket. "Faux leather," he intones. "It just isn't worth it."

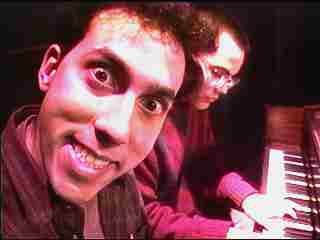

The commercial cast also controls the show's lighting, killing scenes on punch lines and even cutting actors off mid-sentence if the scene threatens to run over two minutes. Right before the first commercial break, a character creates a plot point, to be resolved before the end of the first half-hour episode, which closes with a breezy, hammy theme song improvised by the show's musicians, André J. Pluess and Ben Sussman. After a ten-minute intermission, the emcee gets new suggested conflicts for the second act: the "third-year, mid-season" episode.

Not only does Sitcom stick close to the structure of what's on the air, it holds to the tone as well. On a broadcast sitcom, Janet's lesson at the nude beach would be benign enough-the importance of self-esteem, no doubt-rather than anything as excruciating as discovering that you actually are dull. Sitcom doesn't try to subvert the feel-good code and prides itself on holding to loosely defined "network-appropriate" standards.

The highest compliment here is having people say that it felt just like they were watching TV. In this context, it makes perfect sense to claim, as one cast member does, that "the episode in the morgue was one of the more family-oriented shows we've done."

Still, Sitcom replaces the overwhelming saccharinity that characterizes much television comedy with a high-spirited, kitschy irreverence. Staple sitcom characters-the cloying children, faint-hearted father, sensible mother-are given a twist. "The general rule of thumb," says one cast member, "is make it wacky."

Thus, a letter from the Pope, chastising the priest for his unorthodox methods of raising pastoral attendance, can begin "Dear Boys: Nice try," and conclude with an impassioned plea for the return of bingo night. And when two Iowans inherit an Eastern European spy organization, wackiness ensues when the cold warriors' secret bomb recipe is confused with a cookbook from the heartland, forcing a fervent search for an explosive pie.

Is there something about sitcoms that is particularly satisfying, making the troupe all happier people? "I don't know if it is that gratifying," says John Bourdeaux. OK, is he willing to make the claim that through Sitcom we would all have a sense of harmony and conflict resolution? "You mean, there'd be no war?" he asks, thinking for a moment. "Yeah, sure, why not?"

Goldstein and Bourdeaux hope to be able to keep this group together if they take their show to the North Side, which would count as a happy ending in Sitcom. They also believe they've come up with a way to generate sitcom scripts for Hollywood. "We've come up with some very viable premises, viable characters, and viable locations for sitcoms," Bourdeaux says. "We've come up with them in less than a minute."

"One thing I've learned in science," Goldstein adds, "is that different methods give different results, and writing this way might make a very different kind of product." But even if Hollywood doesn't come knocking, it won't diminish his faith in Structure School Improvisation.

"It's a formula with a good deal of success and big laughs," says Goldstein. "We know that you can never take all the risk out of improv. That's why it's so fun. It's a crapshoot."

Julie Rigby, a freelance writer in Hyde Park, wrote about the campus radio station ("Making Waves") in the August/94 issue.

To see additional photos of the case of Sitcom, click here