John Troha/Black Star

John Troha/Black Star

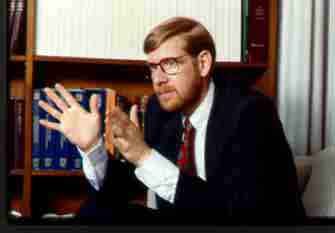

Diplomas and certificates cover the wall behind him, just like in a doctor's office. But where you'd expect an anatomy chart, a tall U.S. flag graces the elegant room on a top floor of the Food and Drug Administration's hulking glass-and-steel headquarters. It feels right that the FDA's Maryland offices lie just beyond the Washington, D.C., Beltway: Its commissioner is an unapologetic idealist who seems to fall outside the image of a federal bureaucrat.

From his outside-the-Beltway post, Kessler, the FDA's chief since 1991, attacks the maladies of misleading food labels and unsafe drugs and medical devices. It's a job for a caring healer and a veteran politico-in fact, Kessler trained as both pediatrician and lawyer.

That training seems to have paid off: The Lord of the Label, as he's been called, is credited with resuscitating an agency that was more used to accommodating industry than regulating it. Having aimed to revive pride among the agency's 9,000-plus employees, this year he's put his popularity outside the FDA to the test, heading one of the strongest threats yet to tobacco companies and cigarette smokers. The much-publicized campaign could bring a regulatory crackdown on teenage smoking.

As he warms up to a question about his job at the FDA, a third Kessler role-that of the passionate consumer advocate-gives voice. "We here end up being responsible for the safety of our nation's food, our nation's drugs, and our nation's blood," he says. "There're thousands of people who get paid within this Beltway to make it their job…to try to influence our decisions. And it's our job, it's my job in particular, to say, `Look, I'm going to allow the scientists, the professionals in the agency, to make those decisions.'"

And Kessler isn't afraid to do his job. He proved it months into his tenure when he ordered the seizure of a shipment of Procter & Gamble reconstituted orange juice misleadingly labeled as "fresh," stunning P & G officials used to a more laissez-faire FDA. The incident soon entered the Kessler lore-even at home, where the commissioner's then-6-year-old son, Benjamin, presented him with a birthday drawing of Dad wrestling a giant juice carton. The man who felt a boyhood admiration for the principled attorney Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird now seems to live the role for Benjamin and his 12-year-old sister, Elise.

The CV includes, of course, both law and medical degrees. Kessler applied to both programs as a college senior in 1973, hoping to defer entrance to law school until he'd finished two years of medical school. Most law schools balked at the plan, he recalls. But at Chicago, he says, "they were very supportive of people doing what they thought they would do best, and they were willing to take risks on people." During the two years he spent in Hyde Park between his second and third years at Harvard Medical School, the "risky" student made associate editor of the law review, and won the school's Casper Platt award for a paper on the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the 1938 law that accounts for most of the FDA's work). Married to attorney Paulette Steinberg Kessler, JD'77, whom he'd met while an undergraduate, Kessler serves today on the visiting committee to the Law School.

His career plan was calculated, he admits, but the goal was health-care administration, not the FDA. In 1981, while still a pediatrics resident at Johns Hopkins, he began working as a consultant on health issues for the Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, chaired by Senator Orrin Hatch. Thanks to his Chicago paper on food and drug law, he became the committee's expert on FDA issues.

Residency over, Kessler kept taking on new jobs. By age 32, he was director of Weiler Hospital at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City. After six years there, he was also lecturing at Columbia's law school, practicing pediatrics in Bronx Municipal Hospital's emergency room, and leading an FDA advisory subcommittee on drugs and biologics. When George Bush nominated him in 1990 to head the FDA, Time called him "almost certainly the most capable person ever put in charge of the Food and Drug Administration." After the White House changed hands, the commissioner, with the backing of many consumer and industry groups, was reappointed by Bill Clinton.

For now, just one job is plenty. Within it, Kessler points out, is "all food, except meat and poultry. It's all drugs, all medical devices, blood, vaccines, biotech. It's cosmetics. It's any device that's radiation-emitting.…The jurisdiction [covers] 25 cents on every consumer dollar."

In two years, injunctions at the agency more than tripled and prosecutions doubled. "The regulated industry knows we mean business," Kessler says with a note of pride. With a limited budget, he argues, strong enforcement "is the way you leverage your resources."

Warning shots like the orange-juice seizure were just the start of Kessler's regulatory attack on deceptive food labels. His most visible work to date, the regulations were mandated by the 1990 Nutrition Labeling and Education Act. Prompting that law was the label tomfoolery that proliferated in the health-conscious 1980s: "low-calorie" desserts with microscopic serving sizes, and "96-percent fat-free" products that were actually loaded in fat.

Under the new rules, terms like "light" and "low calorie" have standard definitions. The biggest switch is the new "Nutrition Facts" panel that must appear on nearly every product made since May 1994. Reflecting nutritionists' chief worries with the American diet, the chart puts fat, cholesterol, and sodium levels first.

"It takes a minute to get used to," Kessler says of the new label. "But give me 30 seconds, and I can show somebody who's never read it how to read it. You look at that `Percent Daily Value' column-it's not a great term-but you look at total fat, and if it's less than 5 percent of your fat for the day, that's low."

Food experts have applauded the changes, though they note that the meat industry and its regulator-promoter, the Department of Agriculture, managed to wrest a few compromises in the reforms.

Kessler calls the project "a tremendous victory for the average consumer," and adds that standardized definitions give food makers an incentive to develop and advertise healthier products. Then the commissioner-a lean man after successfully setting out to lose 50 pounds when he joined the FDA-grins and laughs: "The down side is, now we know what we're eating."

Not all of Kessler's crusades have gotten a uniformly positive reception. In 1992, the FDA curtailed the use of silicone breast implants, after deciding that the products had been marketed without adequate safety studies. Some women and doctors denounced the FDA for overstepping its authority and denying women the right to judge the risks for themselves. The Wall Street Journal-which had welcomed Kessler in 1990 as "a pragmatist who will…look for ways to spare industry from burdensome regulation"-complained that a "Kessler-Congress jihad against breast implants" had prompted a "gridlock" in product approvals, as FDA reviewers put all new medical devices under scrutiny. In other areas, too, like the agency's zealous oversight of drug companies' advertising, some have charged that the new devotion to safety punishes business and treats consumers in a paternalistic way.

Last winter, Kessler proclaimed that tobacco companies deliberately jack up the nicotine content of low-tar-and supposedly low-nicotine-cigarettes. Then, in House subcommittee hearings in March, he posed a loaded question: Are cigarettes a drug?

The answer hinges on whether cigarettes are intended to affect the body's structure or function. In his testimony, Kessler recalled the Surgeon General's 1988 conclusion, since confirmed by an FDA advisory panel, that nicotine is addictive: It affects the body's function. Tobacco companies dispute the finding, starting with the FDA's definition of addiction.

Moreover, Kessler offered the subcommittee evidence that companies manipulate nicotine content-implying, he said, an intent to keep nicotine at addictive levels. Rather than make an outright declaration that cigarettes are drugs-as unsafe "drugs," they'd surely be banned under FDA law-the commissioner closed his testimony more diplomatically. "We seek guidance," he told Congress. His words opened the door to what many see as the only politically possible solution: a congressional mandate for FDA regulation that stops short of a complete ban.

Why regulate smoking at all-especially when other risky activities, from drinking to hang-gliding, are legal? The question makes Kessler sit bolt upright. "Cigarettes are the only product that I know of that, when used as directed, are dangerous. Add up the risks," he demands. "Add up the risks."

With his fingers, he ticks them off in his best courtroom style, no longer the gentle pediatrician: "Alcohol, homicide, suicide, AIDS, illegal drugs...add up the risks from all those, and they pale in the number of deaths per year compared to smoking. One out of five people in this country is going to die from tobacco-related illness."

Which is why Kessler wants to reframe the debate over smoking. "The tobacco companies would have you believe that it's an issue of personal choice. In fact," he counters, his voice almost booming, "it's not an issue of freedom to choose. The recognition that nicotine is an addictive substance very significantly undermines that argument." As does another fault in the logic: "We're dealing with a pediatric disease. Children start at the age of 11, 12-the average age of onset is 14." Many kids, he says, become addicted within a few years of starting. Kessler challenges his listener, "Tell me about the choices when one's dealing with 16- or 17-year-olds who can't quit."

What are the FDA's solutions? "Prohibition's not going to work," he says flatly. Rather than make life tough for today's 45 million smokers, Kessler pins his hopes on today's children: "The fact that, if you don't start smoking by the age of 21, you're not going to start-that gives us enormous opportunity. If we can really stop kids from starting to smoke, the next generation's not going to smoke."

He'd like an end to tobacco advertising that, he says, pitches its message to teenagers. And, he adds, "We need to focus on restricting access. Yes, there are laws against sales to minors, but no one takes them seriously. Until we have the grassroots effort like we saw from Mothers Against Drunk Drivers, we're never going to get there."

Kessler's own call to arms is having some effect. This fall, President Clinton's advisory board on cancer called for increased regulation of tobacco. And an alliance of 75 health, consumer, and religious groups-led by former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop and the Coalition on Smoking OR Health-conducted a national petition drive for laws requiring the FDA to regulate tobacco. A move in Congress toward such laws-one form that legislators' "guidance" may take-could start as early as this spring.

The cigarette makers call regulation of advertising or access just prohibition in disguise-and politically impossible in the wake of November's elections. David Kessler, the FDA's lawyer-commissioner, might count the votes differently. David Kessler the idealist would rather count on the advice of his FDA scientists. He'll do what he thinks is right.

For additional photos of David Kessler, click here