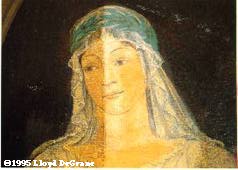

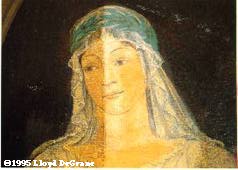

Saving face: Its surface cleaned, the Masque reveals its vibrant colors.

The University of Chicago Magazine

Feb 1995

The University of Chicago Magazine

Feb 1995

Saving face: Its surface cleaned, the Masque reveals its vibrant colors.

In a building designed to instruct University women "in the beauty of living," the third-floor theater of Ida Noyes Hall once hummed with all-female musicals and theatricals, activities that long ago went coed and moved elsewhere. These days-aside from the occasional academic symposium or banquet-the theater is void of activity, save for the painted procession of figures who benignly grace a mural wrapped around the room's four walls.

Known as the Masque of Youth, the mural by Chicago artist Jessie Arms Botke was dedicated January 26, 1918, in a lavish ceremony attended by University president Harry Pratt Judson, sculptor Lorado Taft, and the mural's patron, La Verne Noyes, who called it a "crowning halo" to the building he had donated in the name of his wife, Ida.

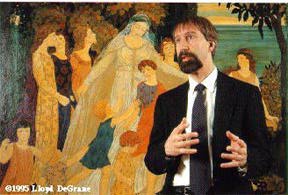

Seventy-seven years later, Chicago artconservator Barry R. Bauman, AM'71, points out signs of the mural's alarming deterioration. A thick layer of dirt and grime, atop a discolored varnish finish, has dulled its colors and flattened its three-dimensional quality. While noting a laudable lack of graffiti for such a public place, Bauman expertly locates numerous scratches, holes, and tears along the surface-as well as several areas where the canvas has pulled free from its plaster support.

With long strides, Bauman now ushers the viewer to two panels on the mural's north wall that he and his assistants, Sarah Kitch and Joe Houston, have carefully restored over consecutive Saturday mornings for the past several months. In contrast to their dingy neighbors, these restored sections glow in a vibrant harmony of colors. Images leap off the canvas as though painted yesterday.

The improvement comes largely from removal of a thick film of dirt on the mural's surface-mostly the product of a certain type of air pollution that Bauman often sees clinging to the surfaces of paintings located "within an hour of Gary, Indiana." Using conservation solvents and what look like large Q-tips, Bauman alone is responsible for the cleaning, because "that's the real moment when paintings can be harmed. If you improperly clean and cause damage to the original paint layer, it's lost forever."

Before cleaning, Bauman's team injects an adhesive to reattach the loose areas of canvas. After cleaning, a ground material is used to fill in chips and scratches, which are then painted to match Botke's original colors. Finally, the entire mural is brushed with a non-yellowing varnish, providing a buffer layer to protect the work from future build-up of air pollution. The varnish, Bauman notes, is easily reversible: "If, in the future, they know more than we know now, they'll easily be able to remove our work."

As founder of the Chicago Conservation Center-one of the nation's top private art-conservation centers-Bauman has worked on Renoirs, Picassos, and Monets at the center's 6,000-square-foot River North laboratory. As far as Jessie Arms Botke's mural is concerned, Bauman's interest in its restoration is personal as well as professional.

He learned of Botke while working as an associate conservator at the Art Institute of Chicago, where one of her paintings is on display. But it was as a graduate student in art history almost 25 years ago that he first encountered her Masque of Youth, immediately falling under the spell of the mural's allegoric pageant of characters: a tall, gray-bearded man, a youthful figure with a crown of spring flowers, lithe athletes bearing Greek bowls and laurel wreaths, and dozens more, traipsing through an idyllic landscape that includes many of the campus' Gothic buildings.

Botke, Bauman later learned, had based the mural on an open-air masque performed during the 1916 dedication of Ida Noyes Hall. According to a University Record from the time, 300 students, alumni, and schoolchildren performed the masque before some 3,000 spectators. The masque's theme-having to do with a personified Alma Mater testing Youth's strength and courage-is by now lost to history. But Botke's murals still gracefully convey the masque's gentle hopefulness and its participants' unquestioning belief in higher learning's edifying powers.

So far, Bauman has been commissioned to work on five of the north wall's six panels, with funding still being sought to pay for restoration of the entire mural.

"Most students probably don't even know they're here," says Bauman, "but the murals are really an anomaly for what you see around campus. I got involved in the project from an emotional point of view, from a memory point of view, and as a conservator. These are quite wonderful paintings that have been neglect-ed for a long time."-T.A.O.

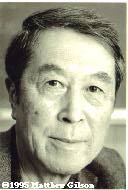

Professor Peter Freund knows two types of physicists. "There are those who think like you and me-when they reach a new result, you can follow the train of thought that led them to what they found. And then there are those exceptional physicists like Richard Feynman, Paul Dirac," and Freund's own U of C colleague, Yoichiro Nambu, 1994-95 winner of the prestigious Wolf Prize in physics, to be presented next month in Israel.

"Of course, one understands what they ended up with, but at the same time," says Freund, "I don't know that I understand how on earth they came up with it. Somewhere in the process, a rabbit is pulled out of a hat...but where that rabbit came from, it's not ever clear."

Nambu, who is the Harry Pratt Judson distinguished service professor emeritus in physics, shares the $100,000 Wolf prize with Vitaly Ginzburg of the Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow. Nambu was honored for his contributions to theoretical particle physics-in particular, for his concept of spontaneous symmetry-breaking, or SSB, which Nambu developed while studying superconductivity in the early 1960s. His theories form an essential cornerstone of the Standard Model, which explains in a unified way three of the four fundamental forces of nature: strong and weak nuclear forces, and electromagnetism.

The Wolf Prize also recognizes Nambu's important contributions to the color gauge theory, which explains how the strong nuclear force governs the behavior of the quarks that make up protons and neutrons in atom- ic nuclei. Nambu's has focused his current research on the question of why the six different quarks have different masses: a consequence, many physicists believe, of SSB. "Why quarks have different masses," he says, "is one of the last unsolved puzzles of the Standard Model."

And how does Nambu go about solving such a problem? He answers, laughing, "I think about it all the time."

Continuing a series of interviews with campus figures, the Magazine's editor talks with Martin D. Runkle, AM'73, director of the University Library since 1980.

The Joseph Regenstein Library turns 25 this September. Is it aging gracefully? All I've ever heard is raves about Regenstein. In its first 15 years, we had a constant stream of visitors because it was of such renown. Faculty talk about how wonderful the Library is. Still, it's not new. The carpets are worn; chairs need reupholstering. Many small things need to be done, but we don't want to spend the money until we can put the work into a larger context.

Our major concern is accommodating the growth of the collections: We're going to run out of stack space in five years. As the stacks get crowded, that creates problems with shelving new books. The collections grow at different rates, so you're constantly shifting volumes. It costs money, and the movement's bad for the books, especially ones that are older and more brittle.

If we run out of stack space without an alternative in place, it will be an absolute crisis. To avoid that, we're undertaking a space-planning project, with help from the Regenstein Foundation.

As part of the project, we'll look at how people use the Library. Increasing the amount of electronic information that we provide access to is a very high priority. Besides the cost of the information itself and the equipment, there's the question of how the building needs to be changed to accommodate the equipment.

We also want to plan how to consolidate some of the building's 16 service stations. The goal is to keep reference desks and other services open longer without spending additional money.

In two years, we hope to have defined a range of options. One solution for the overcrowded stacks, for example, is compact shelving. We could put two-and-a-half-million books in the Regenstein basement that way.

If the building's been stretched to meet new demands, what about the staff-do you have more personnel than 25 years ago? It's about the same-a full-time equivalent staff of 360. Keeping up with electronic information while you're still maintaining the traditional library is an enormous strain. There are staff strains as well as financial strains in trying to integrate those two different worlds.

Electronic information is developing so rapidly. You don't have the controls and filters that you have with traditional publications. It's a jungle out there. At the same time, it's very exciting.

This past fall, a task force planning the future of campus computing recommended a larger role for the Library. How will that mesh with the Library's day-to-day work? Taking over the computer clusters in Harper, Crerar, and Regenstein makes sense. They're in the libraries; we have knowledgeable staff; people already think of the clusters as part of the Library. The task force also recommended that the Library maintain the University's Internet-its Home Page on the World Wide Web.

Helping students and faculty navigate through lots of information is what our libraries are all about. With electronic libraries, you have to invent ways of getting at information on a computer screen and not in physical space. Think of the millions of information items that are, that will be, available. How are you going to guide people through that?

How modernized are the Library's own computer systems? When we started automating in 1968, we developed our system in-house. We pioneered, and our system set a standard. The irony is that it's now badly outdated-but that's soon to change. Over the next two years, we'll install a new system.

A vendor has developed an integrated library system for small to medium-size libraries, based on a modular system called client-server architecture. Chicago and another major university library are negotiating to work with the vendor to scale up that system to meet the needs of research libraries. The number of volumes cataloged, for example, is much higher, our requirements for an accounting system are more complicated, and our circulation rules are far more complicated.

A new on-line catalog will be the first of the system's modules to go up. That should happen within two or three months.

In 1989, the Library stopped updating its traditional catalog. Will the old card catalog ever disappear completely? We have 1.7 million titles in the on-line catalog. We are-very gradually-converting some of the 2 million titles that are only in the card catalog. It's a serious concern: There are a lot of students who simply don't use the card catalog.

But the cost is high. Depending on how complicated a record is, it ranges from $1.50 to $3 per title. We're doing more on-line cataloging by using records from commercial databases. However, some items are unique to Chicago, and we do the cataloging ourselves. Ten years ago, our backlog of uncatalogued material was growing. Now it's staying even.

The value of making the conversion from card to on-line catalog will become clearer as we rely more and more on electronic information. Even now, in terms of competing with other institutions-places like Harvard, which is undertaking a $20-million project to convert its card catalog-there is pressure from students to have the whole catalog converted.

Let's end with a futuristic scenario: Will students in 2005 still need to come to Regenstein or Crerar-or will they simply boot up from their desktop computers? Print is going to be around for a long time. It's true that in a few years abstracting and indexing services in electronic form will totally replace print formats. Still, we have 5.7 million printed volumes-monographs and serials. We add about 125,000 printed volumes a year. It's going to be many years before the majority are put into electronic formats.

As long as we have researchers working with the historical record, we'll maintain those printed volumes-and manuscripts and maps and other formats. We want to do everything we can to make sure that people don't just make do with what they can find on machines.

Even in the electronic-information age, the Library as a place to work won't go away. Some new formats require high-end machines and special equipment or programs-and the Library is where those machines are and where there are people to help you use them.

Geography department-den of spies (February/55):

A Soviet academic journal describes geography chair Robert Platt as a "militant reactionary" whose Wall Street-directed discipline of "drawing up future military battlefields" smacks of "espionage."

One in every 16 U of C alumni is listed in Who's Who; more than 100 are heads of universities and colleges....Hutchinson Commons gets its first thorough cleaning since 1903. The scrubbing reveals "the upper part of the room above the wood paneling is plaster, and not stone as was originally thought."

Cloudy research (February/65):

A device able to make clouds "of any desired density of water droplets at any given temperature" will be used by the geophysical-sciences department to "determine the conditions under which a cloud can be induced to release precipitation."....The site of the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in the now-demolished west stands of Stagg Field is declared a National Historic Landmark....Alumni are invited to the Quadrangle Club for a "festive Roman banquet," followed by a Mandel Hall performance of Purcell's Dido and Aeneas.

Levi departs; chess champs checked (March/75):

University President Edward H. Levi, PhB'32, JD'35, resigns in February to become U.S. attorney general under Gerald Ford....The U of C Press publishes its first cookbook, The Hows and Whys of French Cooking, by Alma Lach....After two years as national champs, Chicago's chess team falls to the University of Toronto at the Pan-American Intercollegiate Championships.

Triumphant: Court Theatre won Chicago's Best Play award at the 26th annual Joseph Jefferson Awards for its autumn 1993 production of Pierre Marivaux's The Triumph of Love. The play marked the Chicago directorial debut of Charles Newell, now Court's artistic director.

Knight life: Philippe Desan, professor in Romance languages & literatures and master of the humanities collegiate division, is now a Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Palmes Academiques (Knight in the Order of the Academic Palms)-France's highest distinction for academics and artists. Desan's latest book, Montaigne, will be published in France this year.

Antarctica live: The first live TV broadcast from the South Pole featured a U of C astronomy team headed by Mark Hereld, principal investigator for the South Pole Infrared Explorer (SPIREX). The broadcast-an interactive teleconference linking scientists with two secondary-school classrooms-aired January 10 on more than 230 PBS stations. SPIREX is one of several projects within the U of C-managed Center for Astrophysical Research in Antarctica.

Little red survey: Results are in from a recent survey of some 330 alumni who were students in the University's "Little Red Schoolhouse" class for academic and professional writing, with 89 percent of respondents rating the LRS as extremely or highly useful in their own writing. Further, 83 percent judged the quality of their own writing to be "good" or "excellent," and 89 percent said writing was "relevant" or "central" to their success.

Sultan's chair: The Turkish government contributed $200,000 toward establishing the Kanuni Süleyman Professorship in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Studies-and commited to giving half of the $1.5 million total needed for the chair, provided the University raises matching funds within the next two years. The chair's name honors a 16th-century sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Other news: A $350,000 Mellon Foundation grant will support three yearlong, interdisciplinary faculty-student seminars on the theme "Confrontations with the Other." Directed by humanities, social sciences, and Divinity faculty, each seminar will support one postdoctoral and three dissertation fellows.

Policy docs: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has established a Clinical Scholars Program at the University. One of seven such U.S. programs, it provides two years of post-residency, graduate-level training for physicians in policy-related research. The program's director is Christine Cassel, AB'67, the George M. Eisenberg professor in medicine.

Winning coaches: Women's soccer coach Amy Howley Reifert was voted the University Athletic Association's (UAA) Coach of the Year, and head football coach Dick Maloney and his assistants were named UAA Coaching Staff of the Year. Reifert-who has coached at Chicago since 1990-led her team to its first-ever UAA championship this past fall, while Maloney's first year as football coach yielded 17 team records and 5 wins.

Fresh approach: Shifting away from languages and literary history, the former Department of Germanic Languages & Literatures-now called the Department of Germanic Studies-has been redesigned to emphasize cultural studies. Starting in 1995-96, eight new concentrations will provide a general introduction to German culture and analyze specific aspects of that culture-such as psychoanalysis and the role played by Jewish culture in the German-speaking world.

Supreme clerks: Seven recent Law School grads were chosen to serve as clerks for Supreme Court justices: Susan Davies, JD'91; Griffith Green, JD'93; H. Kent Greenfield, JD'92; Thomas R. Lee, JD'91; Jody Manier, JD'93; Lisa Schultz, JD'93; and Craig Singer, JD'93. They will do research, help draft opinions, and assist the justices in sifting through thousands of appeals to pick cases the Court will review.