For

half a century, Robert Griesbach, PhD'55, has cultivated his garden,

working to build a better daylily. Griesbach's latest is a deep

purple beauty - named for his U of C mentor.

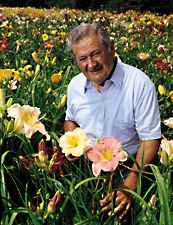

On

his five-acre farm, nestled between crops of corn and soybeans

in Delavan, Wisconsin, Robert Griesbach, PhD'55, spends his summers

tending to more than 10,000 daylily plants that form a tightly

packed field awash in hues ranging from pink and red to yellow

and near white. Yet every year or so, he disrupts this tranquil

scene by digging up and transplanting a few choice blooms, before

applying herbicide to kill off the remaining thousands. The next

year, he starts the process over by replanting the field with

seeds produced from hand pollination.

On

his five-acre farm, nestled between crops of corn and soybeans

in Delavan, Wisconsin, Robert Griesbach, PhD'55, spends his summers

tending to more than 10,000 daylily plants that form a tightly

packed field awash in hues ranging from pink and red to yellow

and near white. Yet every year or so, he disrupts this tranquil

scene by digging up and transplanting a few choice blooms, before

applying herbicide to kill off the remaining thousands. The next

year, he starts the process over by replanting the field with

seeds produced from hand pollination.

|

|

Robert

Griesbach, PhD'55

|

The ritual is part of Griesbach's six-decade pursuit

of new daylily varieties. To date, he has introduced some 60 new

daylily plants through a number of nurseries, including Klehm's

Song Sparrow Perennial Farm in Avalon, Wisconsin, and Wayside

Gardens in South Carolina. A professor of biological sciences

at DePaul University for 34 years, Griesbach developed a new method

for doubling the chromosomes in daylilies-with four sets of chromosomes,

tetraploids offer more color possibilities. His latest creation

is a deep, velvety purple daylily to be named in memory of his

mentor at the University of Chicago, botanist Paul Voth, SM'30,

PhD'33.

Griesbach's father, a church organist and choir

director, grew irises and other flowers on their city lot in Menasha,

Wisconsin. Though always interested in plants from working with

his father, Griesbach's interest in daylilies blossomed upon coming

to the University and doing graduate work under Voth. A 1940 Quantrell

winner who himself had studied under U of C botanist and daylily

breeder Ezra Kraus, PhD'17, Voth suggested that Griesbach study

daylily dormancy and germination to arrive at a more exact reading

of the effect of cold temperatures on deciduous daylilies.

|

What

prompted breeder Robert Griesbach's interest in daylilies

was, he explains, the realization that "daylilies were going

to become the most important garden perennial."

|

Voth was a dedicated mentor, hand-pollinating daylilies

to produce the seeds Griesbach used in his experiments. Unlike

evergreen daylilies, which keep their foliage year round and grow

well in the southern United States, deciduous daylilies lose their

foliage in the fall and are more common in the northern United

States. Griesbach found that deciduous daylily seeds must be in

the ground at a near-freezing temperature for six to eight weeks

before they start to develop; they can still germinate after being

exposed to slightly warmer conditions, but must remain at those

conditions for a longer period of time. His findings helped give

evidence to what had previously only been noted anecdotically.

After completing his graduate work in botany at

Chicago, Griesbach returned to teach at DePaul-where he had earned

his bachelor's and master's degrees-in its biological-sciences

department, eventually chairing the department for 14 years. At

DePaul, he was able to blend his scientific work in cytology and

the genetics of polyploidy (plants with more than the normal number

of chromosomes) with what quickly became a lifetime interest in

breeding daylilies. "My research and my hobby were all combined,"

he says. "I continued school, so to speak, on Saturdays and Sundays."

What prompted his interest in breeding daylilies,

he explains, was the realization that "daylilies were going to

become the most important garden perennial." It's a strong statement

from a generally mild-mannered professor, but he saw plenty of

evidence to back his argument: Daylilies can flourish in a variety

of soils, temperatures, and light intensities. They also have

a long growing season, from late spring to autumn; every day brings

a new group of blossoms; and, in the northern United States, they

can be grown without being mulched. But perhaps their greatest

feature is being extremely resistant to fungal and viral diseases.

Today, Griesbach's confidence has proven well-placed: The American

Hemerocallis Society boasts over 10,000 members, publishes the

quarterly Daylily Journal, and hosts regional and national conventions

and growers' competitions.

|

Griesbach began his breeding experiments by working

to develop tetraploid daylilies, which have four sets of chromosomes

instead of the two sets common in many plants. In increasing the

number of chromosomes, his goal was to deepen the daylily gene

pool and thus expand the possible variations of color and other

physical attributes. Taking the seedlings left over from his dissertation

experiments, he treated them with the chemical colchicine, which

caused their cells to begin to divide-creating a duplicate copy

of the chromosomes-without completing the cell-division process.

This plant was left with cells with the genetic material for two

individual cells.

Two years after his tetraploid first bloomed in

1959, Griesbach formally introduced the new flower. Crestwood

Evening, which he had collaborated on with breeder Orville Fay,

made its debut at the 1961 National Daylily Convention in Chicago.

The new tetraploids were noticeably different from

their diploid ancestors. With twice as many chromosomes, cell

nuclei were larger. With larger cells, the tetraploids had larger

flowers, leaves, and roots. An increased root system meant that

the tetraploids could absorb more water and nutrients, and thus

grew more vigorously. Doubling the chromosome number also meant

that the tetraploids' color could be more intense, because the

new plants could have as many as four doses of a given pigment,

while diploids could only range from zero to two doses.

Not all of the results were desirable. The new plants

were stiff and sometimes brittle. And, because they were temperature

sensitive, the first generation of tetraploids was not very fertile:

if the temperature exceeded 80° F, pollination would most likely

not take. But Griesbach eventually found that such undesirable

qualities could be bred out of the daylilies in second, third,

and fourth generations.

Asked to name some of his favorite creations, Griesbach

thinks over his answer carefully. Ruby Throat, Towee, Baltimore

Oriole, Painted Trillium, and Blazing Sun win the honors. "One

of my interests was to work on certain colors that, at the tetraploid

level, were not very well established, and red was one of them,"

he explains. Ruby Throat and Towee, for example, offered a clearer,

less muddy red than previously available. Although he has worked

on many colors to improve their clarity (how pure a color is),

saturation, and intensity, Griesbach admits that all his favorites

fall in the reds and purples.

|

Retiring in 1989, Griesbach moved to Wisconsin with

his wife, Mary Lou, in 1991. The relocation took two years because

he had to transfer two crops of flowers-daylilies and lilies.

In the end, Griesbach transplanted several thousand plants from

his home in Park Ridge, Illinois, to his new farm in Delavan,

Wisconsin. His summer 2000 crop now includes 3,000 daylilies blooming

for the first time this year and representing 150 different parents.

Of these 3,000, only three to four will be improved enough for

possible naming and introduction; those improved but not significantly

improved enough for introduction will be used for crosses to produce

seeds. The hope is that with each generation, the resulting plants

will become more and more improved in terms of the particular

trait for which Griesbach is breeding them.

Among the flowers growing in his field are several

plants of the Dr. Paul Voth daylily, to be registered with the

American Hemerocallis Society this summer. Griesbach plans to

introduce the flower to the public in 2001, which will be sold

through Klehm's. Griesbach chose to name this deep, velvety purple

daylily after Voth both because, as daylily hues go, it's one

of the more "manly" hues, and because it's in Griesbach's own

favorite color range. "Dr. Voth was the one who really got me

interested and involved with daylilies in the first place," says

Griesbach. "I learned so much from him about daylilies, I just

feel that it's very appropriate to honor him in this way."

![]()

On

his five-acre farm, nestled between crops of corn and soybeans

in Delavan, Wisconsin, Robert Griesbach, PhD'55, spends his summers

tending to more than 10,000 daylily plants that form a tightly

packed field awash in hues ranging from pink and red to yellow

and near white. Yet every year or so, he disrupts this tranquil

scene by digging up and transplanting a few choice blooms, before

applying herbicide to kill off the remaining thousands. The next

year, he starts the process over by replanting the field with

seeds produced from hand pollination.

On

his five-acre farm, nestled between crops of corn and soybeans

in Delavan, Wisconsin, Robert Griesbach, PhD'55, spends his summers

tending to more than 10,000 daylily plants that form a tightly

packed field awash in hues ranging from pink and red to yellow

and near white. Yet every year or so, he disrupts this tranquil

scene by digging up and transplanting a few choice blooms, before

applying herbicide to kill off the remaining thousands. The next

year, he starts the process over by replanting the field with

seeds produced from hand pollination.