|

||

|

Peer Review ::

Into the bowels of comedy

Television writer David Goodman defends scatological sensibilities.

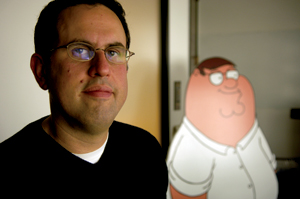

Family men David Goodman (left) and Peter Griffin.

The FCC has a problem with defecation,” says David A. Goodman, AB’84, of the forces policing his hit animated show Family Guy. Indicted by the Parents Television Council as one of 2005’s worst shows for children, the Fox TV series thrives on slapstick gags, pop-culture jibes, toilet humor, and the antics of bumbling middle-class dad Peter Griffin and his Rhode Island family. The show also takes on its critics. In one episode Peter launches his own TV station in retaliation for an FCC crackdown on his favorite shows—the fall-out from a David Hyde-Pierce “trouser malfunction” at the Emmys. A catchy musical number sums up the censors—“They’re as stuffy as the stuffiest of special-interest groups. Make a joke about your bowels and they order in the troops.”

Commandos have yet to ambush Goodman’s Los Angeles office, but Family Guy’s executive producer and head writer admits the show’s ribald scribes push the envelope. Still, he sees hypocrisy in the regulatory system. “It’s a negotiation without clear parameters,” he says of FCC guidelines. While a Family Guy character sitting on a toilet gets a thumbs down, CBS’s CSI: Crime Scene Investigation runs decapitations and blown-up body parts in the same 9 p.m. time slot. “That’s a lot more traumatic,” Goodman muses, “than Peter’s cartoon behind.”

It’s a double standard the veteran writer—his resume includes The Golden Girls, Star Trek: Enterprise, and a string of “very forgettable sitcoms”—thinks is over the top. And he’s got bad news for cleanliness crusaders. “The show taps into a culture that’s already there,” Goodman says of Family Guy’s core teen-to-30s demographic. “This is what people are finding funny.” The ratings concur; the show is consistently in the top ten among adults 18–34 and often number one among teens. Its first- and second-season DVD is the second best-selling television series on the market, just behind Chappelle’s Show.

But popularity doesn’t necessarily make Family Guy family-safe. Goodman’s own kids, Jacob (9) and Talia (6), who are strictly limited to one half-hour of TV on weekends only, have never seen the show. “This is not a cartoon for kids,” he emphasizes. “There’s material in here I don’t really want to have to explain to my children.” It’s a stance his mother, Brunhilde Metlay Goodman, AM’48, likes to remind him is a touch hypocritical, but Goodman doesn’t waver: “Watching TV is a choice, not a right. If you’re going to have kids, take responsibility for them. If you agree with the Parents Television Council, then listen to them. Don’t let your kids watch Family Guy.” He pauses, then laughs. “Does that sound like one huge rationalization?”

Hailing from a line of academics—his father and uncles were professors—Goodman originally intended to scale the University’s ivory tower as a political scientist. Instead he “realized what a mediocre intellect I was” and spent as much time contemplating Hill Street Blues and the final episode of M*A*S*H as Strauss and Machiavelli. After graduation, he returned to his native New York and took a subsidiary-rights job at Simon & Schuster. There he met television writer Gloria Banta (The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Rhoda), who encouraged him to try his hand at sitcoms. At age 25, after writing a spec script for the show, he landed a writing gig on the top-ten hit comedy The Golden Girls. “It was a little heady,” says Goodman of his climb from being “essentially a secretary” to rubbing elbows with Bea Arthur and Estelle Getty. One thing that didn’t faze him, however, was the age gap between himself and the show’s characters. “They’re four old ladies who talk like four guys in their twenties,” says Goodman.

When he joined Family Guy as a writer in 1999, Goodman instantly hit it off with series creator Seth MacFarlane, who soon promoted him to executive producer. But trouble was brewing. Hoping to compete with NBC’s Friends, Fox had switched the show to 8 p.m. Thursday during its first season. After that, ratings plummeted from a high of 21 million viewers—Family Guy premiered right after the 1999 Super Bowl—to a paltry 5 mil. A few weeks into season three, the ax fell. As remaining episodes aired, the staff sent out résumés. Though disappointed, Goodman took it in stride. “I’ve been on so many shows and they all get canceled,” he jokes, “I was kind of the comedy pallbearer.”

But Goodman underestimated the show’s fans. Although angry petitions had failed to save it, outpourings of love—in the form of record DVD sales for released episodes and soaring ratings for Cartoon Network reruns—seduced network execs. Fox reenlisted the Family Guy cast and crew, sending them back to work in April 2004.

Two years later Goodman, MacFarlane, and 15 writers are still stirring up outrageous repartee for Peter & Co. Each episode is a long journey—from first draft to final airing can take up to a year—that Goodman doesn’t take lightly. “If you’re enjoying the writing process,” he says, “you’re probably writing a bad script.”

Asked which character in his television career he most identifies with, Goodman rewinds past Family Guy to the short-lived Fox sitcom Flying Blind. “It was about a Jewish guy from the New York suburbs who ends up with this very downtown New York girlfriend—and he’s sort of this nerdy, suburban kid. It was a very easy show for me to write,” he says laughing. But don’t typecast: Goodman also did a cameo as the voice of Jesus Christ in last year’s Family Guy movie. “I’ll give almost anything a try,” he admits, “except Desperate Housewives.”