|

||

|

Rational choice

A research center focused on Chicago price theory gets a new moniker that’s long been a household name in economics: Becker.

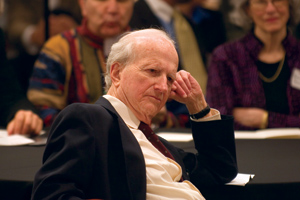

Considering the arguments: Gary Becker focuses on the price-theory panel at hand.

Why has sub-Sahara Africa borne the brunt of the AIDS epidemic? What is a profitable publishing strategy in the Internet age? Why does the public come to believe as fact information that is demonstrably false? How will medical research’s shift from a microscopic to molecular perspective affect health-care delivery?

These questions and scores of others were asked at the inaugural conference of the Initiative on Chicago Price Theory, held April 7–8 at the Graduate School of Business Hyde Park Center.

Their range underscored a key characteristic of an economics approach known as Chicago Price Theory: research that focuses on the crucial role of markets and incentives in all aspects of modern life. The approach is synonymous with Chicago names (and Nobelists) like Ronald Coase; Milton Friedman, AM’33; George Stigler, PhD’38—and Gary Becker, AM’53, PhD’55, the University professor in economics and sociology, for whom the campus-wide research initiative, housed in the GSB and led by economists Steven Levitt and Kevin Murphy, PhD’86, will be named. On July 1 the initiative becomes the Becker Center on Chicago Price Theory, Founded by Richard O. Ryan.

Ryan, MBA’66, was among 170 friends, students, and colleagues on hand to fete and gently rib Becker during a tribute dinner. Guity Nashat Becker, PhD’73, told of meeting her husband while failing to barter down the price of a used dining-room table he wanted to sell. Richard Posner—senior lecturer at the Law School, judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, and Becker’s co-blogger—praised “Gary’s unflinching desire to follow rational-choice theory...wherever it may lead.” Proclaiming that “Gary Becker has been a household name in my household for as long as I can remember,” Chicago statistics professor Stephen Stigler noted that his economist father had termed Becker “the premier theorist of human capital.” And in presenting Becker with a first edition of Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, Murphy blended past accomplishments with present endeavors: Becker, he concluded, “pushes economics in every direction he can.”

A grateful Becker noted that, at first, he wasn’t thrilled to have a center named in his honor: “That usually happens when you’re either dead or completely retired.” What helped morph reluctance into pride, he said, is his belief in the “constant” at the base of the “changing tradition” of economics: “It will be judged on how well it helps us understand the world—and how it helps us improve it.”

Understanding the world and how to improve it provided topics for the conference’s five panel sessions on markets and incentive issues in finance, the environment, health and disease, the media, and the end-with-a-bang session on The Biggest Questions of the Day. Framing those big questions were Berkeley economist and 2001 Nobel laureate George A. Akerlof; Harvard economist Edward L. Glaeser, PhD’92; and Becker.

Akerlof’s hit list included three global issues and one national problem. A better understanding of market forces could be marshaled to alleviate global warming, poverty in underdeveloped countries, and the possibility of worldwide macroeconomic collapse. Close to home, Akerlof pointed to a concern that has long been a subject of Becker’s work: “The continued disparity between whites and blacks is a leading problem that is special to the United States. We see this in the discrepancy between incarceration rates of whites and blacks, and in the differences in numbers of single-parent families.”

A common thread, Glaeser emphasized, linked the big questions posed by terrorism and anti-Americanism, religious and ethnic conflicts, the lack of democracy in countries with relatively uneducated and unskilled populations, and health-care inequities. That thread is “false belief,” or a disconnect between what is and what people believe to be true. “Parents, teachers, politicians, the media, religious leaders are all in the belief-formation business—all are occasionally the suppliers of truth or the suppliers of error,” Glaeser said. “It’s the nexus between psychology and economics,” an intersection of situations and persuasion ripe for further analysis.

Becker vetted the lists, using them as a starting point for future research questions. On global warming: “Initially I was skeptical of the evidence, but now I’ve been convinced. The question is: What will the solution be?” Terrorism: “What can be learned through economics about who becomes a terrorist? What are the factors that determine it? We know it’s not poverty in any simple sense.” The “American dilemma” of black-white issues: “Why haven’t blacks caught up? Why has there been a slowdown in the convergence since 1990?” On false beliefs and the power of persuasion: “How do you chart the interaction between the desires of the persuader and the desires of the persuadee?”

With that, he opened the floor—and the Becker Center—to still more questions whose answers, he hopes, will make a difference.