|

||

|

Features ::

Lost Nubia

James Henry Breasted’s century-old photos, recently on display at the Oriental Institute Museum, provide a glimpse of ancient Nubian sites since drowned.

OVER TWO WINTER SEASONS, in 1905–06 and 1906–07, Oriental Institute founder James Henry Breasted led University-sponsored expeditions throughout ancient Nubia—today’s southern Egypt and northern Sudan. Although archaeologists had considered Nubia a subset of Egypt, Breasted helped show that, although enmeshed in Egyptian life, it was a separate culture—and one whose preservation was uncertain. After the Nile River’s low Aswan dam, built in 1899–1902, began to expose ancient Nubian monuments to yearly flood damage, Breasted and other scholars realized some sites eventually might disappear under the rising reservoir. To record the monuments, he and his teams—the first trip included wife Frances, son Charles, engineer Victor Smith, and photographer Friedrich Koch; the second included photographer Horst Schliephack and Egyptologist Norman de Garis Davies—took almost 1,200 black-and-white photos, developed on 8 x 10–inch glass plates and lugged by camel and ship along the Nile. When a high Aswan dam was planned in the 1960s, Chicago sprang to action again: OI teams helped UNESCO excavate sites threatened by the new dam’s resulting floods. Today the monuments north of Aswan and into southern Egypt are under water—much of Nubia is, in fact, lost.

While all of Breasted’s photos can be viewed online (oi.uchicago.edu), 63 of them were chosen for a temporary exhibit and catalog accompanying the opening of the museum’s final permanent installation, the Robert F. Picken Family Nubian Gallery. The photos were displayed through May 14, and plans are in the works to send them to Egypt’s Nubia Museum of Aswan—their first trip back since they were shot 100 years ago.

Photos by James Henry Breasted’s expedition team

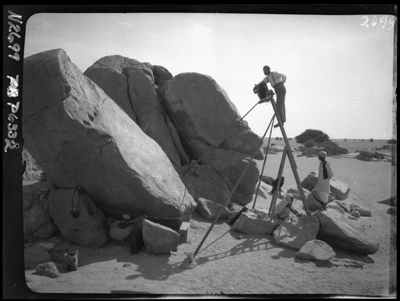

Breasted captured Schliephack photographing the Great Stela of Thutmose

I at Tumbos. Thutmose, an Egyptian king, ordered the monuments to mark his

victory over the Nubians around 1520 BC. One inscription, Breasted wrote

in his field notes, bears the first Egyptian mention of the Euphrates. January

10, 1907.

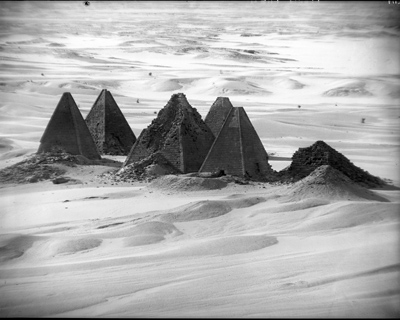

Although he didn’t try aerial photography until 1920, Breasted appreciated

the vantage point that the 98-meter-high Gebel Barkal mountain offered of

the Napata pyramids. Schliephack, telephoto lens, December 1906.

In Hafir, the main town in a remote area south of the Nile’s third

cataract, some farmers eat their midday meal in the fields rather than returning

home. Here, Breasted learned, “all postal connections cease for over

a hundred miles,” and his team would have no outside contact for four

weeks. Breasted, January 6, 1907.

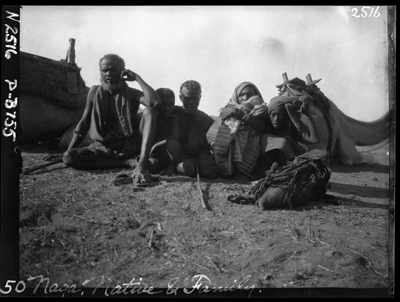

A Sudanese family at Naga, the southernmost ancient site that the expedition

visited during its second season on the Nile, stopped by to see what the

foreigners were doing. Two camels kneel in the background. Breasted, mid-November

1906.

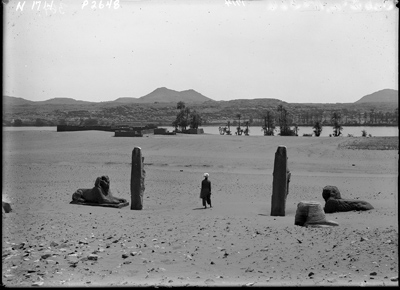

Facing east toward the Nile, this photograph shows the start of the Avenue

of Sphinxes, the formal approach to the Temple of Ramses II at El-Sebua.

During a 1960s UNESCO preservation campaign, the temple was reconstructed

about 4 km to the west, on the Lake Nasser shores. Koch, December 31, 1905.

The Temple of Abahuda reveals how sacred spaces were recycled. Commissioned

by Pharaoh Horemheb (1319–07 BC) to worship two Egyptian gods, in

the Byzantine period it was converted to a church. The interior reliefs

were plastered and painted with Christian saints and angels. Koch, January

17, 1906.

On the Nile’s west bank, the Abu Simbel monuments were covered by

sand dunes until discovered in 1813. In 1906 a cascade of sand still separated

the Great Temple of Ramses II and the Small Temple of the goddess Hathor.

The day this photo was taken, Breasted learned of U of C President William

Rainey Harper’s death and hung his ship’s U.S. flag at half-mast.

Koch, January 22, 1906.