|

||

|

Original Source

Take one tablet...

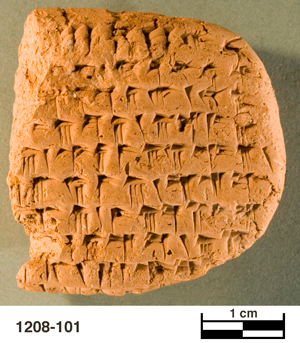

In an old cardboard box at the Oriental Institute, Assyriologist Matthew Stolper last year found, he believes, the tip of an iceberg: an ancient Iranian tablet inscribed in Old Persian. It is the only known tablet of its kind. “The settled belief among scholars, including me,” Stolper says, “has been that in the Persian Empire, Old Persian was used only for formal, royal purposes”—cliff-face inscriptions or palace engravings. For the empire’s day-to-day affairs, scribes relied on Aramaic, Babylonian, or Elamite, an indigenous language that predated Old Persian by 2,000 years.

But the OI tablet, one of thousands on loan to the museum from Iran since 1937 as part of the Persepolis Fortification Archive—which in 2001 became the subject of a lawsuit against the Palestinian militant group Hamas—is an ordinary administrative record. It details the payout of 600 quarts of a dry commodity near Persepolis, in southwestern Iran. The tablet could be an anomaly, Stolper says, but most likely it’s evidence that Old Persian was used more widely than known. “Administrative texts don’t work in isolates; they work by the hundreds and the thousands,” says Stolper, who heads the OI’s Persepolis Fortification Archive Project. “It’s like finding one tax form and saying it’s the only one there ever was.”

So far, however, the Old Persian tablet, which dates to 500 BC, is the only one. Stolper believes others may yet be unearthed. In fact, he says, the Persepolis archive offers a parallel: “Prior to the discovery of these tablets, only one Elamite text had ever been found anywhere. And then in 1933, archaeologists found tens of thousands of them.”

Stolper’s finding also demonstrates that even after 70 years, the archive still holds surprises, a fact that motivates his research as the lawsuit threatens to take the tablets away. “This has become an emergency,” he says. “It means this work is the complete focus of all my research.”