|

||

|

Peer Review ::

Cuban crescendo

Young rappers raise their voices—and Castro’s government listens.

The Alamar housing project, about an hour outside Havana, shelters some of the city’s poorest people, many from Cuba’s black communities. Two decades after its 1970s construction, Alamar sparked a growing rap movement fueled by young Afro-Cubans frustrated with a government that neglected racial inequities. Though Fidel Castro organized conferences during the late 1950s to address racism, he later dismissed race as a resolved matter; Cubans were Cubans, and to identify oneself by race was seen as unpatriotic. Such official pronouncements, many rappers argued, further marginalized Afro-Cubans. “For blacks I keep asking the question,” goes a lyric by rap group Junior Clan. “Where is your voice?”

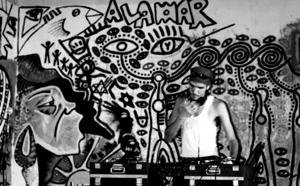

Against a graffiti-art backdrop, a DJ spins records at the Alamar hip-hop

festival in 2001.

Sujatha Fernandes, AM’00, PhD’03, is listening to those voices. Fernandes, the Australian-born daughter of Indian parents, is author of Cuba Represent! Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures (Duke University Press, 2006). A political activist during her undergrad years at the University of Sydney, she organized protests and petitions to fight discrimination against Australia’s immigrant and indigenous peoples. Others her age seemed apathetic—until she discovered hip hop. In Sydney’s western suburbs young immigrant rappers sang against police brutality, white supremacists, and prejudice, all the issues that concerned Fernandes. A singer and percussionist since childhood, she formed rap group Deadly (Aboriginal slang for “cool”) and from 1995 to 1998 performed at Sydney festivals, rallies, and benefits. Among their hits: a militant song imploring Australians of color, raised on American sitcoms like The Brady Bunch, to “counter those images with our own realities.”

From Sydney to Alamar, Fernandes says, rappers and other performing artists passed over traditional institutions to voice their political concerns. In January 1998, three months before starting her doctorate at Chicago, Fernandes traveled to Havana to help her journalist sister edit a radio documentary on three generations of Cuban women. Connecting with local jazz and rap musicians, she ended up playing clubs and rap festivals for three months. Fernandes arrived in Hyde Park that fall, her “head still full of Cuba.” She switched her focus from Indian religious movements to the politics of Cuban rap, art, and film.

“When people look at politics,” says Fernandes, now an assistant sociology professor at Queens College, City University of New York, who made several trips to Cuba between 1998 and 2004, “they look at political pacts, parties, traditional institutions, but they don’t necessarily look at popular fiestas and rap music.” Yet around the world, these public-performance spheres are where questions of race and identity come to the forefront. And in a country like Cuba, where state agencies register musicians and oversee film production, such questions, says Fernandes, seep into official debate and discourse.

Government involvement is not always immediate. When the rap movement hit the Alamar housing project in the 1990s, its performers were still largely underground and unmanaged by the state. The official state response, says Fernandes, was disregard. As the mostly free concerts grew from 100 people to 500-plus, however, the state “began to recognize that these young people were not just a cultural, but a political force.” Between 1995 and 2001 the Asociación Hermanos Saiz, the cultural branch of the state youth organization Union of Communist Youth, took over rap-festival planning. As Cuban Minister of Culture Abel Prieto told Fernandes in 2001, “Cuban rap music represents the dramas and issues that people from marginalized barrios are raising. ... We need to be supporting it.”

Fernandes doesn’t see the government’s policy shift as a “classic case of co-optation.” Part of the reason for the state’s support, she argues, is that rappers’ messages of equality—and the notion of rebelling to achieve it—already reflect Cuban socialist and revolutionary ideals. While some rappers have “gone commercial,” attracting foreigners with salsa-infused songs about cigars and other Cuban icons, the government prefers to support “underground” rappers who reject capitalism. In 2001 Prieto praised young musicians for the “seriousness and rigor with which they take on real problems, at the same time rejecting commercialism.”

The Cuban government, still suffering economically from the Soviet Union’s 1989 collapse, recognizes the marketability of the minority experience. Especially in film, stories like Fernando Perez’s La Vida es Silbar (Life is to Whistle), which debate Cuban identity, are in heavy demand across the globe. As such, argues Fernandes, talking about race in Cuba has become “much more acceptable.”

With Castro’s five-decade rule nearing its end, many Cubans expect these discussions to continue when younger brother Raúl takes power. Unfortunately, says Fernandes, few ethnographers may be around to document what happens; over the past three years the country has become increasingly closed to foreign travel.

Sensing this trend, Fernandes switched her research focus. For her next

book, In the Spirit of Negro Primero: Urban Social Movements in Chávez’s

Venezuela, she again analyzes popular politics through local music

and arts (as well as a new component: life histories), but this time in

the shantytowns of Caracas. Plagued with gang violence, the barrios are

an area few researchers study. Still, like the Alamar projects, says Fernandes, “if

we want to understand how people are talking about politics,” these

are the places “we have to go.”