Spare Me

Is Jack Tucker, PhD’72, a professional bowler? That’s what his classmates have been reading in the Magazine’s “Alumni News” section for years. As his (much embellished) essay makes clear, the truth can get lost in pursuit of the score.

By Jack Tucker, PhD‘72

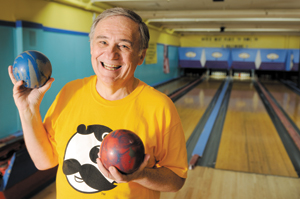

Photography by Dan Dry

I’m one of those not-so-unique individuals who got his doctorate from the University of Chicago but never managed to find a career in the life of the mind. The year, 1972, turned out to be a terrible one to face the job market in Eastern European social history. Maybe I didn’t know how to market myself effectively. Or maybe it was because there was a huge glut in the supply of graduating PhDs and a shrinking demand from the smaller market of post–baby-boom college students. All I know is that there weren’t jobs for my graduating year. Even assistant professors back then knew they weren’t going to get tenure and were taking law courses at night or becoming Amway distributors, hawking cleaning supplies to the wives of full professors. Sadly, I concluded that history had no future.

I tried to make peace with the demise of my career dreams and instead went about looking for a regular job. Suddenly I was confronted with an even uglier reality, unimaginable inside the confines of Hyde Park: to the rest of the world, PhD was a title given to overeducated dummies. Employers all assumed that if you had a doctoral degree, you were either overqualified for any normal position or you were some sort of idiot savant too incompetent to do anything. For example, I applied for an intern position with the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (no, not the organization charged with passing out marijuana cigarettes to Hebrew youth—though I’ve heard they pay very well—but rather the one that tries to provide relief to foreign Jewish communities in distress). I didn’t get the internship even though I was qualified and had a good interview. I could tell that behind it all was the prejudice that if you’ve got a PhD, you are ruined for real work.

For a while, I considered eliminating my degree and entire graduate-school experience from my résumé and telling everyone that for the last six years I had been living in an ashram. Even yoga masters were considered more employable than people with a doctorate.

Things worked out, though, thanks to my parents. I went into the family nursing-home business, and I did well. I’d like to believe that I even did good, but that’s for others to say. But I guess I always harbored a certain resentment that my original goal of becoming a famous historian never quite materialized.

One day in 1987, I was reading the University of Chicago Magazine, and I checked out the class-notes section that trumpeted the many splendid achievements of my fellow graduates—you know, the PhD who has now written the definitive scholarly work on the antediluvian period, the LLD who is now the solicitor general for some inconsequential governmental agency, the MD dermatologist who is now treating zits in the suburbs, or the MSW who is administering an NGO dedicated to raising consciousness about a problem no one else is interested in—and I suppose I was jealous.

Out of the blue, I thought I might poke fun of the University and all its pretensions. I decided to write in my own entry as a spoof of academic achievement: “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, of Baltimore, MD, is on tour with the Professional Bowlers’ Association”—my highly idiosyncratic way of saying that a University of Chicago PhD is not necessarily worth anything in the real world. And, unbelievably, the University of Chicago Magazine published this notice just as I sent it in. Some local friends in Baltimore, also U of C alumni, called saying they appreciated my sense of humor, but no one else, certainly no one from the history department or its diaspora whom I knew from the old days, ever contacted me.

As happens to all compulsive liars, my initial publishing success led me to see how much I could get away with before I was exposed. A year or two later, the Magazine was reporting to its many readers: “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, is a professional bowler and last June prevailed at the prestigious Sandusky Open.”

A few years would pass before the announcement of another great triumph: “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, is a professional bowler and last November came in first against many of the greatest names in professional bowling at the Kalamazoo Invitational.”

The thrill of the lie became obsessive. Every few years, not so often as to raise any hints that this was a hoax, there would be a new report of another victory in a bowling match taking place in some minor Midwestern city, each lie slightly more outrageous than the one before: “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, is a professional bowler and this past April triumphed in the Carson City Classic with a sudden-death win over Redmond Smathers, last year’s victor. To defeat Smathers, Tucker needed to bowl no less than eight straight strikes against his champion opponent.” Pretty impressive, wouldn’t you say?

Then a few minor announcements would appear that were not overly remarkable in and of themselves, but were designed to add credibility to the process:

- Jack Tucker, PhD’72, a professional bowler and a member of the Professional Bowling Association, has recently become the professional spokesperson for the Ironweed Bowling Shoe Company of Wilkes Barre, PA, which reminds the bowling public that if the shoes don’t fit, the pins will split.

- Last December Jack Tucker, PhD’72, testified in Washington, DC, before the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Professional Sports Injuries. His subject was “Recurrent Achilles Tendon Injuries among Professional Bowlers: Time Wounds All Heels.”

- Jack Tucker, PhD’72, participated in the convocation of the American Bowling Congress held last March in Terre Haute, IN, on the subject of Feminism and Bowling. His paper was titled, “A Strike by Women Will Keep Men’s Balls out of the Gutter.”

A few years later I would return to my dominant theme with astounding feats of accomplishment: “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, is a professional bowler and this past year achieved a career first. He hit the Grand Slam of professional bowling, winning the Rochester, MN, Classic in March; the Grand Rapids Invitational in June; the Akron Open in September; and the Tournament of Champions in Cedar Rapids, IA, this past November.”

My penultimate tall tale appeared in the June 1996 Magazine: “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, a member of the Professional Bowling Association, was elected to the Bowling Hall of Fame in 1995. Also in 1995, he won the Ypsilanti Invitational and the Wheeling Open Bowlers’ Competition. In 1994, he was named Professional Bowling magazine’s man of the year after winning both the Sandusky Invitational and the PBA Open for the third time.”

Again I never heard from anyone, and I started to speculate whether anyone was reading the alumni magazine at all. Or the history-department newsletter, for that matter. The news of my most recent glorious triumph was repeated in the 1995–96 newsletter for the benefit of all history faculty, graduate students, and alumni—this time without my own instigation. But still no calls from people who knew me from my Chicago days. Or maybe I was such a negligible personality that no one recalled me at all. No one ever wrote to question my purported achievements. Nor did any of my old professors, the ones who had always preached the necessity of skepticism for every historian, ever read these reports and wonder enough to contact me. So much for the dictum of the great Leopold von Ranke, father of the profession, who held that to be true, any historical fact must be corroborated by two independent sources. I could not help but wonder if, when I was a student, my professors had read my dissertation with any more care or interest than they now read the pages of the history-department newsletter.

It was time to submit one final lie to the University of Chicago Magazine. But coming up with one was a toughie. How could I top being selected for the hall of fame? For a while I toyed with the thought that because my persona was a champion athlete, perhaps I should portray myself as having succumbed to the usual temptations of postmodern athletes. “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, is a championship professional bowler who was recently expelled from the Bowling Hall of Fame and stripped of his many other honors as a result of a positive blood test indicating that his many victories were possibly achieved with the aid of anabolic steroids.” Or “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, was recently arrested after being discovered in a hotel room in Dayton, OH, with a 13-year-old male prostitute. The following day Mr. Tucker released a statement informing the public that he was suffering from alcoholism and addiction to pain medications that were responsible for his inappropriate behavior, and that he was immediately checking himself into the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, CA. He sincerely requests that his many loyal fans pray for him.” Reluctantly, I rejected these striking (forgive the bowling pun) ideas not because they were unbelievable—just the opposite. But no college graduate would crow about these kinds of achievements in the alumni magazine.

After much deliberation, I went with a less eye-catching but somewhat more proper report, tailored neatly for the class-notes audience: “Jack Tucker, PhD’72, is a champion professional bowler. He retired from academic history in 1973 but maintains his interest and is writing a book titled A Social and Economic History of Bowling from the Druids to the Age of Don Weber.” I thought that was a particularly nice touch—mimicking historians’ jargon by calling the mid 20th century “the Age of Don Weber.” Don’t you always flinch just a little when you see a history-book title referring to the early 18th century as the Age of Giambattista Vico or the late 19th century as the Age of Henry Adams? No doubt, in some future era historians will recall the early 21st century as the Age of Adam Sandler.

I was still wondering if anyone at all was reading those notices I kept sending to the alumni magazine when suddenly I was confronted by more proof than I could have imagined: an unsolicited phone call from an official of the Newberry Library, the famous research facility on Chicago’s North Side. At first I thought it might be a joke, so I told him I had a momentary crisis with one of my children and asked for his number so I could call him back. No problem, he replied. When I phoned back, I reached the Newberry switchboard. Unbelievably, the guy was legit.

He explained the reason for his call. The Newberry was seeking to publish a new, scholarly Encyclopedia of Chicago, which would contain everything that an educated, informed reader should know about the history, ethnology, geography, economy, ecology, etc., of the city. The library needed a writer to pen an article on the history of bowling in Chicago. Someone at the University had referred him to me as one of the world’s leading authorities on the topic. Of course, I was not necessarily a specialist on bowling in Chicago, but I was a PhD alumnus in history from that illustrious university on the South Side, and a professional bowler. Perhaps I would consider writing an article, no more than 2,500 words, on the History of Bowling in the City of Chicago for this encyclopedia. Unfortunately, he apologized, the Newberry had a limited budget, but he was willing to pay me a nominal fee of $500 upon completion of the work. Could I research the subject and write such an article in, say, six months?

How could I refuse an invitation like that? Without hesitation, I agreed to research and write the article within six months and invited him to send me a contract. He did, and I signed it.

I phoned all my Baltimore alumni friends who had been following my putative achievements in the Magazine about my latest, amazing academic coup: Jack Tucker, PhD’72, is a professional bowler who will be writing the History of Bowling in the City of Chicago for the Encyclopedia of Chicago, a project of the venerable Newberry Library. My article would, no doubt, be definitive and would probably preclude any future scholar from even investigating the subject.

I started planning my article. I was not going to do anything by way of research, of course. A liar, after all, has his honor to protect. Everything I wrote was to be completely fabricated. My mind was brimming with ideas.

Maybe I should take the romantic approach. I’d write about how for generations, the awful lives of the toiling laborers—the tired, the poor, the huddled masses who came to the City of Big Shoulders from Ireland, Germany, Eastern Europe, and the Orient, the sharecroppers who came up from the Deep South, the poor whites who migrated from the Appalachians and the Ozarks—all had been assuaged by their chance to bowl a few frames. I’d immortalize the story of those who slaved in the stinking abattoirs, in the lint-filled textile mills that generated brown lung disease, in the greasy machine shops with their ear-shattering din, in the noxious foundries with their toxic fumes, in the unbearably scorching blast furnaces and steel mills belching out pungent black smoke—of all whose pathetic lives had been made endurable by the few happy moments of bonhomie in the bowling alleys, hooking balls and knocking down pins while guzzling a brewski and wolfing down a sausage. I’d insist that no less an authority than poet Carl Sandburg had once proclaimed, “The bowling lanes of Chicago are the country clubs of the masses.” Maybe I’d even write about how bowling lanes were the only place in that segregated city for people of all religions, races, and ethnicities to meet and recreate over ten frames. I’d call the article “Bowling: That Quintessentially American Sport Finds Its Home in America’s Second City.”

Or I’d take the Great Man/Woman approach:

- In 1889 Jane Addams helped her immigrant clients assimilate to New World culture by having each of them roll a few frames at the Hull House bowling lanes.

- Mayor Richard J. Daley and ward boss Joseph Rostenkowski, father of later U.S. Representative Dan Rostenkowski, met in 1918 while working as pin boys at South Side Lanes. Each went on to organize competing bowling teams that became the bases of their respective political machines.

- Archbishop George Mundelein received his red hat from Pope Pius XI in 1924 after the Holy Father read in L’Osservatore Romano’s sports section an article celebrating the Chicago prelate’s perfect game—a first by any member of the Catholic hierarchy.

- The St. Valentine’s Massacre of 1929 actually occurred in a garage outside the Clark Street bowling lanes. Al Capone started the argument when Bugs Moran passed the foul line during an otherwise friendly match between competing teams in the Illegal Whiskey Distributors Bowling League.

- The very first commission that architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe received in 1937 after emigrating from Germany to Chicago was to design the revolutionary new Bauhaus Bowling Lanes in Cicero.

- Just before Christmas 1942, University of California, Berkeley, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer arrived at the University of Chicago to be personally briefed by Enrico Fermi about the results of the great Italian’s first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction under the stands of Stagg Field. After a short discussion about scientific matters, the two researchers became terrified by the bloodcurdling implications. They promptly retreated to the nearby University gym to break the tension by rolling a few ten-pin games. Oppenheimer’s diary notes, however, testify to the tremendous frustration the Berkeley physicist felt when he missed no less than seven easy spare opportunities. “I am become death,” he recorded, “the destroyer of worlds.”

By the time my six-month research period had expired, I had drafted an article on the history of bowling in Chicago that I could honestly claim was virtually unprecedented in the history of scholarship. Unfortunately, the article had one major critic: my wife.

“Did it ever occur to you that your editors and publishers might not think this article is quite as funny as you do?” she asked.

“It’s not supposed to be funny to them. Only to me. Besides, what’s funny is not the article, but rather their gullibility.”

“So you think that by publishing the article in their encyclopedia, it will hold them up to ridicule. But you do realize that they are probably spending several million dollars on this encyclopedia?”

“So?”

“So, some people might not think that publishing a spoof in a scholarly encyclopedia is such a benign undertaking. You are not simply taking $500 for nothing. When the editors find out, they might reasonably think that you ruined their entire enterprise, and they just might not believe that returning the $500 gratuity would repay them for the loss of confidence in their encyclopedia’s authority.”

Gosh, I never thought of it that way. For the first time, I comprehended that this practical joke might engage me in a legal action involving a liability of millions of dollars. Perhaps everything I had built up over the years and then some might be at risk. What would my defense be? Revenge for not getting the academic job I thought I deserved? Suddenly the whole project was not as funny as I had thought.

I quickly phoned my editor at the Newberry and apologized for not being able to complete my assignment. Well, take a few more months, he suggested. No can do, I replied. The other demands of my career. The press of business. Writer’s block. My reserve company had been called up. I was suffering from AIDS. Whatever. I just could not complete the assignment, I insisted.

My failure to perform as expected must have pissed off a lot of important people and opened up the whole question of my qualifications for the job. The people at the Newberry consulted with the U of C history department and with the people at Alumni House. Every claim I had previously made was now open to scrutiny. Had I really written the so-called definitive history of bowling? Was I really elected to the Professional Bowling Hall of Fame? Was there even a Professional Bowling Hall of Fame? Had I won the Ypsilanti Invitational? Was there such a place as Ypsilanti, Michigan? Was I even a professional bowler? For that matter, had I ever bowled a single frame? Suddenly the spirit of skepticism, the desire not to accept anything as true merely because it had been published, re-entered these institutions. In one fell swoop, all my achievements collapsed like a house of cards. I was exposed as a fake much as Ptolemy’s geocentric theory of the universe had been dispatched by Galileo.

A carefully worded disclaimer appeared in the history-department newsletter: “Jack Tucker, 1972: Jack, why are we having such a hard time finding a copy of your book on Druids and bowling?—Editor.”

I had been revealed as a fraud. I half expected the newsletter’s exposé to be reported in the National Enquirer. “Outrage: University of Chicago PhD Tries to Scam Intellectual Public.” Inquiring eggheads want know. Call 60 Minutes.

So my double life was laid bare. Do I have any misgivings? Do I regret my life of deception, especially because the search for truth was the hallmark of my academic education at the University of Chicago? Well, not really. I probably am not the first historian to make up facts to prove his thesis. Maybe not even the first to get a PhD from Chicago. In fact, I probably am not the first alumnus to exaggerate his life’s achievements in the University of Chicago Magazine class notes. Besides, as Ptolemy said after he was finally overturned by Galileo, “It was a great run while it lasted.”

Bowled over

By Amy Braverman Puma

When the Magazine staff first read Jack Tucker’s essay chronicling his bogus class-news items about his professional bowling career and related scholarship, we thought it was funny. Then we realized how bad his feat made us look: clearly the editors had not been fact-checking the alumni news closely enough. Still, we can laugh at ourselves, so we told Tucker we would run the piece. But this time we would check everything.

A tenacious intern combed each class-notes section of the Magazine since 1972 as well as the archives of the history department’s newsletter—it stopped printing in 1998. Between the two publications she found only four of his many supposed notes. So I called Tucker up.

The story, he said, was “substantially true as I remember it.” Then he admitted, “I used a lot of creative license” in the essay—adding many more items for satirical effect. “The bit about the Newberry Library,” Tucker said, “is absolutely true.” Well, almost. He never actually penned the false article for the Encyclopedia of Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 2004). It took him about four months to back out of the assignment, confirms James Grossman, a U of C senior researcher in history, a VP at the Newberry, and a coeditor of the encyclopedia. Had Tucker actually submitted a fabricated piece, Grossman assures, the editors’ “elaborate fact-checking procedure”—clearly more elaborate than the Magazine’s—would have caught the lies.

Tucker’s aim, in both his faux-news items and in his essay, was to poke fun at academic pretensions. And when no one ever questioned him, he believed, the bowling tales became all the more ironic. “Every time I published one of these lies, I expected to hear from someone” at the University. His “biggest lie,” in his opinion, was his induction into the Bowling Hall of Fame. “I don’t even know if there is a Bowling Hall of Fame.” (There is. It’s in St. Louis.)

This essay isn’t Tucker’s first published piece. After graduate school he wrote a cooking column, “The Ghastly Gourmet,” for the now-defunct Baltimore News American’s Sunday magazine, and during a brief teaching stint at Boston University he penned “The Odious Epicure” for the Boston Globe’s Sunday magazine. Since selling the family nursing home in 1995, Tucker—a 1966 Johns Hopkins graduate whose three sons, aged 17–26, all eschewed Chicago, he says, for being “too intellectual” and having “no football”—has returned to writing. One story, about dealing with his father’s Alzheimer’s, appeared in the Fall 2000 Reform Judaism magazine.

The University of Chicago Magazine editors, with Google’s help, try to double-check suspicious-sounding class news. But with a staff of five editors and two interns, we can’t verify everything. Tucker’s right: he’s not the first alumnus to submit false news, nor the first whose inventions made it into print. And—this isn’t meant as a dare—he won’t be the last. Call it a job hazard: we have to trust our readers.

Return to topWRITE THE EDITOR

DISCUSS THIS ARTICLE

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

MORE FROM THE MAGAZINE

RELATED LINKS

- The Encyclopedia of Chicago

- International Bowling Museum and Hall of Fame

- Professional Bowlers Association