Lost in the Second City

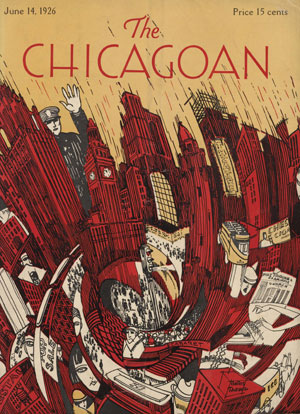

“Like a new-born babe, yelling lustily,” was how the Chicagoan announced its arrival in June 1926. Nine years later, it folded. And then it vanished.

By Lydialyle Gibson

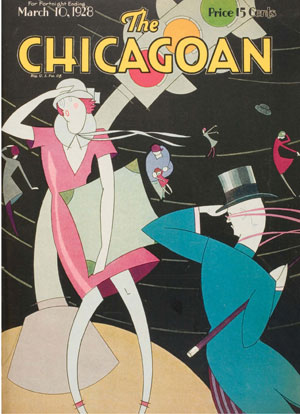

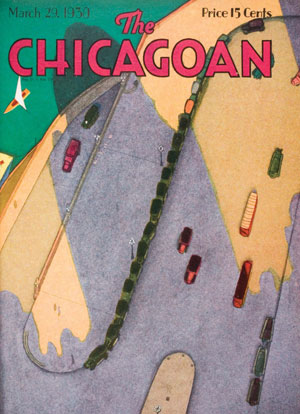

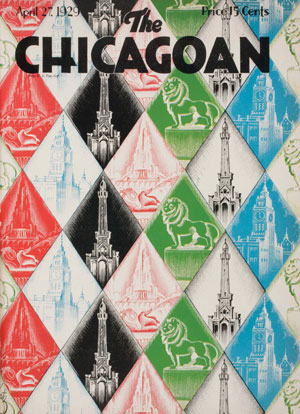

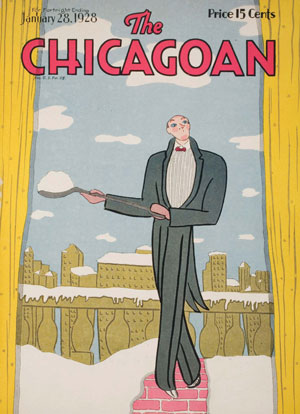

Images from The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age, published by the University of Chicago Press. Artwork courtesy of Quigley Publishing Company, a division of QP Media, Inc.

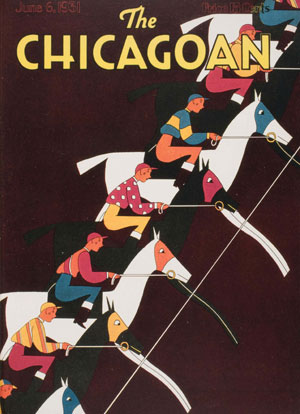

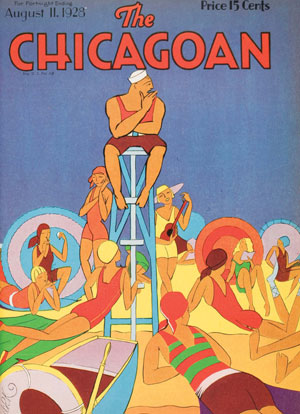

What first caught Neil Harris’s eye were the colors: yellows and reds and lurid greens, deep-sky turquoises, heated pinks, oranges, violets, and surreal, majestic, arresting black. Dating from the 1920s and ’30s, every magazine cover stood ablaze, each topped with the same banner, proclaiming, in oversized Art Deco lettering, the Chicagoan. Inside he found tart commentaries, passionate reviews, pithy vignettes, photographs, poetry, and cartoon after cartoon. “I was astonished,” says Harris, the Preston & Sterling Morton professor emeritus of history and art history. The Chicagoan was clearly an ambitious undertaking, one that chronicled a vibrant decade of the city’s evolution, and Harris, a cultural historian who had spent his career studying American metropolitan life, had never heard of it.

He unearthed the Chicagoan by accident: a dozen years ago, searching the Regenstein Library stacks for some other book, he happened across nine drab-looking bound volumes with the magazine’s name written across their spines. They were, he would discover, one of only two substantial collections in existence (the only full set belongs to the New York Public Library). Seventy-three years after the Chicagoan folded, most copies have vanished, along with, Harris soon learned, nearly every archival document relating to its history.

The magazine itself offered few clues to its identity. Contemporary publications rarely mentioned the Chicagoan, and its masthead and bylines yielded mostly unfamiliar names. So Harris turned to old census records and telephone books, library archives—at the Regenstein and elsewhere—and descendents of Chicagoan editors. His research culminated in The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age, published this November by the University of Chicago Press. Stretching across 400 oversized pages, the book offers an expansive portrait of a magazine that at its best had a “finish and flair,” observed a 1931 Time magazine review, “worthy of a national publication.” Harris sketches the Chicagoan’s run in a lengthy introduction, and an appendix compiles brief biographies of writers, artists, and editors. For the most part, though, Harris lets the magazine speak for itself, reprinting covers, articles, art, and advertisements as they first appeared. The book reproduces the July 2, 1927, issue in its entirety, including stage and cinema listings—the Tivoli Theatre on Cottage Grove was showing Clara Bow in Rough House Rosie that week—and a back-page ad for a Steger Victrola. “In today’s world, we like to think that nothing ever disappears, that everything is documented,” Harris says. “This was a journal that at its peak had 20,000 subscribers. And it disappeared.”

The Chicagoan launched June 14, 1926, just 16 months after the New Yorker, from which it took obvious, sometimes shameless, inspiration. It was led by editor Marie Armstrong Hecht, ex-wife to famous journalist Ben Hecht, and publisher L. M. Rosen, “whose other accomplishments remain,” despite Harris’s research, “so far, hidden from history,” Harris laments. Promising a fashionably urbane outlet for “the intellectual and social desires—music, arts, theatres, books, social activities and even sports”—in a city that “needs make no obeisance to Park Avenue, Mayfair, or the Champs Elysees,” the Chicagoan assumed the role of champion for its namesake city. In the 1920s Chicago endured what Harris calls a “mounting chorus of disrespect.” Despite its skyscrapers and jazz clubs and deep well of literary talent, the city’s reputation was for crime and corruption: Al Capone and his gangsters, Mayor “Big Bill” Thompson and his cronies. The Chicagoan couldn’t resist Capone’s sensational exploits, either, but it countered with profiles of leading citizens and boosterish articles with headlines like, “How Do You Like Chicago?”

In his editorials, publisher Martin J. Quigley, with his wife Gertrude, railed against “the same jeers Chicagoans have responded to ever since,” Harris says.

Whatever its success in restoring the city’s good name, one certain triumph for the Chicagoan, Harris says, was its artwork. The cartoons and caricatures were smart and satirical. The covers, depicting still-new landmarks such as Buckingham Fountain and the Board of Trade, displayed humor and elegance. Their originality and artistic quality were “as good or better,” Harris says, “than the New Yorker’s.”

The most constant guiding hand at the Chicagoan belonged to Martin J. Quigley, who took over as editor and publisher in March 1927, after a brief, unexplained hiatus in publication. A devout Catholic and former Chicago news reporter, Quigley had built an empire of Hollywood film-industry journals and helped write the 1930 Production Code that set rules for on-screen morality. “Whatever Chicago was and was to be the Chicagoan must be and become,” Quigley declared in a 1931 editorial. The contributors amassed under his stewardship included a number of U of C graduates and professors. Milton Mayer, X’29, assistant to University president Robert Maynard Hutchins and a Great Books instructor, wrotesome of the Chicagoan’s most serious and complicated essays, on Nazi Germany, the Red Menace, and presidential politics. His August 1932 contemplation, “The State of Beggary,” accompanied photos of homeless Chicagoans sleeping in Grant Park, while a brightly lit Michigan Avenue looked down, as the caption hinted, “not so benignly, perhaps.”

Still, like so many publications, the Chicagoan was never quite able to attract enough advertising, and after nine years, it died. What puzzles Harris is how little has remained. “Not a letter, not a bill, no receipt or a single comment beyond a few letters in Milton Mayer’s papers” at the Regenstein’s Special Collections Research Center.

The April 1935 issue turned out to be the last. “There was no warning, no announcement,” Harris says. “It was just gone.” Now it’s back.

Return to topWRITE THE EDITOR

DISCUSS THIS ARTICLE

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

RELATED LINKS

WEB EXTRAS