Etching modern life

By Lydialyle Gibson

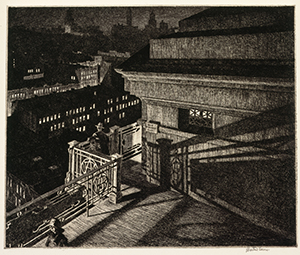

Image courtesy the Smart Museum

Between 1850 and 1940, as modernity transformed cities in Europe and America—factories booming, tenements burgeoning, bridges and tall buildings crowding the horizon—the art of etching also ballooned. Its evocative immediacy and intimate scale gave artists an ideal medium, says art historian and literary scholar Elizabeth Helsinger, to express the experience of living in an increasingly alien and alienating landscape. Helsinger curated a Smart Museum exhibit (up through April 19) exploring the “etching revival” in France, Britain, and the United States, particularly how etchers’ visions of modernity echoed those of the era’s writers: Dickens, Hardy, Balzac, Woolf, Poe, Baudelaire. Helsinger plans a winter class on the same topic.

“Etched vision,” she writes in the exhibit catalog, “can render everyday objects and scenes unfamiliar and disturbing, imbuing them with powerful emotional qualities—unexplained fear, loneliness, and sorrow, the troubling shadows of urban modernity.” Cityscapes depicted urban waterfronts, industrial fringes, outsized buildings. The countrysides unfolding in landscapes were hardly the pastoral idylls of 17th-century Rembrandt etchings.

Limited to black and white, artists like Martin Lewis used “the language of light and dark” to intense effect. In his 1928 East Side Night, Williamsburg Bridge (above) a lone man stands outside a men’s room, his back to the viewer, facing a dark urban canyon that implies, writes Helsinger, “a city’s lonely populousness.”