|

|

|||

|

About the Magazine | Advertising | Archives | Contact | ||

|

|||

Brain art

A neuroscientist and artist balances two seemingly divergent careers.

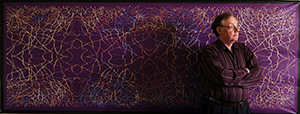

Audrius Plioplys, MD’75, has dedicated his life to the biology and philosophy of thought. A Lithuanian American neurologist and researcher who has worked for hospitals and clinics in his native Toronto; Rochester, Minnesota; and Chicago, he has studied neurological conditions from autism to Alzheimer’s with grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Illinois Department of Public Health, among other organizations.

In digital prints like Displacement (above), Plioplys finds the beauty in brain waves and in the ways neurons “produce consciousness, morality, society.”

His neurobiological research is also channeled through a different medium. For more than 30 years, Plioplys, who goes by Andy, has combined neuroscience and art, producing paintings and digital prints that reflect the brain’s inner workings.

In 1980, for example, while working in the electroencephalogram (EEG) laboratory at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Plioplys decided to see how his own brain operated. He had a technician take his EEG—a measurement of the brain’s electrical activity—while he pondered prepared “artistic topics,” he says, like Vermeer and Lithuanian artist Čiurlionis. His 2005 collection of digital prints, Symphonic Thoughts, shows his brain waves as a central element in each piece.

Two earlier print series, Neurotheology (2000, first shown at Chicago’s Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture) and Thoughts from Under a Rock (2003, reissued in 2004 using a different printer, inks, and canvas), use drawings by early 20th-century Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramon y Cajal. Cajal, writes Plioplys in his artist’s notes, “published three landmark articles about the neuronal fine-structure of the human cerebral cortex,” winning the 1906 Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine.

Plioplys filled each large canvas with one of six colors—yellow, red, blue, orange, green, and purple. From the background color he digitally subtracted Cajal’s neuronal drawings, which exposed another layer: a photograph of a significant event or place from his travels. The photos are distorted to reflect the brain’s process of remembering. “The neuronal arborizations,” he wrote in exhibit notes, “divulge artistic memories, artistic processes, and creative thoughts.”

Neuroscience first gripped Plioplys while he was a U of C undergrad. A series of lectures during his second year—he entered medical school after his third year—“absolutely mesmerized” him. The lecturer, Quantrell Award–winning professor Richard Mintel, SB’60, PhD’65, roused Plioplys’s interest with the ways neurons “produce consciousness, morality, society.”

Since moving back to Chicago in 1990, he has served as director of four children’s nursing facilities, worked for Michael Reese and Mercy hospitals, and taught at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago (1991–98). On the art front he joined forces with the contemporary-art gallery Flatfile Galleries in Chicago’s Fulton Market district and has exhibited his art throughout the city. Several pieces from the Neurotheology series are on permanent display at the University. One hangs in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel’s Interreligious Center: Thoughts of Ancestral Religious Rites: Pilviskiai, Lithuania. Two others adorn the Donnelley Biological Sciences Learning Center’s first floor. And with the April 30 reopening of the city’s renovated Blackstone Hotel—the site where, in a “smoke-filled room,” Republican leaders selected Warren G. Harding the 1920 presidential nominee—he sold the hotel six works from his Thoughts from Under a Rock series. The prints hang in the hotel’s fifth-floor boardroom.

Plioplys’s red-brick mansion in Chicago’s Beverly neighborhood, where he lives with his wife Sigita, is also an exhibition space. Huge versions of brightly colored, abstract digital prints hang above antique-looking furniture, and smaller pieces line his staircases. Three framed faces created from mirror slivers—Kafka, Dostoyevsky, and Beckett—line the hallway, a shrine to the writers who inspire him. A case dedicated to the craftwork of his sister Ramute, AB’74, sits in one room. After her 2007 death, Plioplys gathered all of her pieces, including Lithuanian drilled eggs: teardrops and dots delicately carved through a drained shell.

His home serves as his studio. In an upstairs office, amid piles of books and binders that store images from past installations, Plioplys keeps two PCs to create his prints. Sometimes it takes more than an hour to complete a single step, he explains, and he needs more than one computer to tackle different tasks simultaneously.

Above the computers are some of his earlier, 11 x 17–inch works. A 1987 piece shows its title, Do Letters of the Alphabet Contain Thoughts? surrounded by a jumble of lowercase letters. In My Personal Method of Thinking in Polychrome (1988, acrylic on paper), Plioplys wrote the multicolored words “over and over” in rows across the page.

“Words are essential,” he says; his art “is not just visual.” In his Neurotheology series, he printed each work’s title directly on the canvas—for example, Mathematical Thoughts, University of Chicago or Thoughts of Displaced Sanctity, Rocky Mountains, Colorado—in Arial font. With the title written on the front, the viewer sees more than simply the picture, Plioplys argues: he also sees the artist’s thought process. But his audience didn’t like that particular aesthetic. “People protested,” he says, and he’s since stopped incorporating the titles.

In recent years Plioplys has cut down his time practicing medicine, partly because of health problems including recent eye surgery for a retinal detachment. He now spends one day a week as an outpatient child-neurology consultant for Advocate Health Care Plans and another day at Marklund Children’s Nursing Home in Bloomington, Illinois, working with children with severe cerebral palsy.

He continues his artistic exploration of the brain and maintains a comprehensive Web site, plioplys.com, where he reflects on each piece. After Chicago’s Balzekas Museum hosted a 2006 retrospective of Plioplys’s art, he has been working on “several cycles of sequences of things”—but he refuses to get specific. “When I talk about it,” he says, it’s bad luck.”

He learns through the process of creating, as some ideas work and others transform into new ones. The “vast majority of complex images get scrapped,” Plioplys says, and he often has to start over. But that’s his personal method of thinking: “over and over.”