Color lines

After a brief segregated past, the U of C emerged as one of the few places to welcome African Americans to its academic ranks.

By Amy Braverman Puma

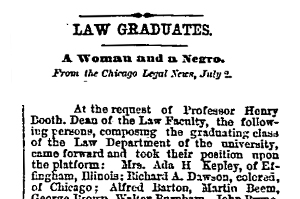

In 1857, four years before the Civil War, Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas donated ten acres a few blocks north of Hyde Park to found a new institution of higher learning. In keeping with the city’s First Baptist Church, Douglas and the university’s other trustees maintained a segregated school. But in 1870, the year the 15th Amendment gave blacks the right to vote, the university granted law degrees to a woman (Ada Kepley) and an African American (Richard Dawson). The Chicago Tribune noted their achievements: “Law Graduates: A Woman and a Negro.”

Negro History Bulletin, 1939

Negro History Bulletin, 1939

Zoology scholar Ernest Everett Just, PhD’16, was one of several African Americans whom former Biological Sciences Division dean Frank Lillie recruited and supported.

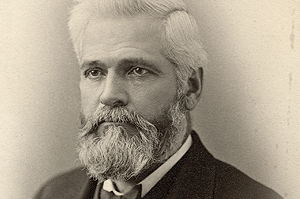

University President William Rainey Harper, shown circa 1900, helped keep Chicago open to black students.

The 1928 Cap and Gown shows Samuella G. Caver, PhB’28, participated in extracurriculars, something earlier black students seldom did.

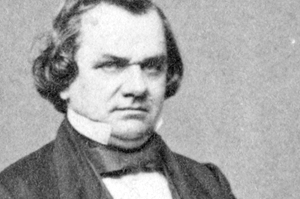

Senator Stephen A. Douglas donated the land on which the Old U of C was built.

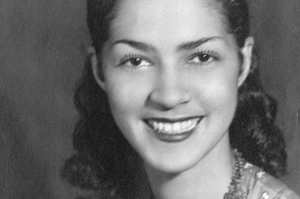

After leading the 1939 Cap and Gown beauty contest as a write-in candidate, Geraldine Lane Mardis, AB’40, AM’53, was forced to withdraw.

The new University of Chicago, established with a donation from John D. Rockefeller, continued the former institution’s tradition of admitting African Americans and women.

Opportunity, 1925

Opportunity, 1925

Monroe Nathan Work, AB 1902, AM 1903, was the first African American to earn an advanced degree at Chicago and later worked at the Tuskegee Institute.

Galusha Anderson was a loyal Unionist.

Courtesy the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives

Courtesy the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives

Georgiana Simpson, AB’11, PhD’21—forced to move off campus as an undergrad—became one of the first black women to earn a PhD, in German philology.

Chicago Public Library Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History & Literature

Chicago Public Library Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History & Literature

At the 57th Street Art Colony, blacks and whites could interact in an environment accepting of diversity.

By the early 1880s the institution, today known as the Old University of Chicago, faced foreclosure—Douglas’s racial views were one factor that hindered fund-raising. The school’s president, Unionist Galusha Anderson, testified that Chicago had always admitted women and, since the 15th Amendment, blacks. His testimony “created a myth,” says historian Danielle Allen, former dean of the Humanities Division, that obscures the more complicated history.

It’s a history not many people know, says Allen, who curated the Special Collections Research Center exhibit Integrating the Life of the Mind: African Americans at the University of Chicago, 1870–1940, sponsored by the Black Metropolis Research Consortium and on display through February 27. “We are left to speculate,” she writes, “that the association of the Old University of Chicago with Stephen Douglas may explain the later suppression” of the first institution’s origins.

Allen realized the Douglas connection while searching for those first African Americans to enroll at Chicago. Faculty and administrators had been wondering who they were the past few years, as the News Office compiled notable African American alumni for its Web site. “Nobody knew the answers,” she says. So her project began. Starting with about 15 names, her spreadsheet now includes almost 240.

When Harper and Rockefeller founded the new U of C in 1890, they continued the old university’s (eventual) commitment to openness; the first class included an African American, Cora Bell Jackson, AB 1896. Over the next several decades, when not many schools admitted blacks, Allen writes, “a few independent-minded administrators and scholars consistently helped clear the path” at Chicago.

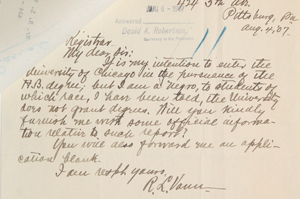

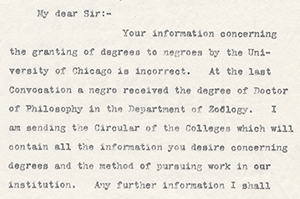

In August 1907 prospective African American student Robert Lee Vann wrote to the University to ask if Negroes were admitted.

The president’s secretary promptly responded, including application information. Vann ultimately attended the University of Pittsburgh.

The Old University of Chicago was founded in 1857 and razed in 1890.

The July 9, 1870, Chicago Tribune announced that a woman and a Negro graduated from the U of C law school—both were firsts.

In 1884 foreclosure proceedings, Old U of C President Galusha Anderson testified—incorrectly—that the school was always open to all students.

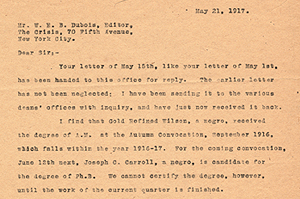

After W. E. B. DuBois wrote to the University in a letter dated May 15, 1917, the assistant recorder responded May 21 with the names of graduating African American students.

The Old University of Chicago was founded in 1857 and razed in 1890.

While academic life was encouraging, social life was not. To help out at home, many blacks took U of C summer courses, patching their educations together. On campus, racism abounded. In 1907 graduate student Cecelia Johnson, PhB 1906, was accused of trying to pass for white to join a sorority. She was outed in the Tribune. That same year, Georgiana Simpson, AB’11, PhD’21, later among the first black women to earn a doctorate, was banished from her dorm. And in 1939 Geraldine Lane Mardis, AB’40, AM’53, was forced to withdraw from the Cap and Gown beauty contest.

Despite these difficulties, by 1943 some 45 African Americans had earned Chicago PhDs—more than at any other university. Those degrees aided the broader fight for equal rights; Allen uncovered letters from W. E. B. DuBois asking about Chicago’s admission policies. “We hadn’t realized how much the civil-rights movement depended on African Americans with advanced degrees,” she says. And by educating black scholars, the University played a part. “It’s stunning to me that the U of C doesn’t know its own role in history.”

Return to topWRITE THE EDITOR

DISCUSS THIS ARTICLE

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

RELATED LINKS

- Integrating the Life of the Mind: African Americans at the University of Chicago, 1870–1940

- Special Collections Research Center (SCRC)

- Black Metropolis Research Consortium

- Danielle Allen at the Institute for Advanced Study

RELATED READING

- Chicago Chronicle: ‘Integrating the Life of the Mind’—Library to put Chicago’s rich history of African-American intellect on display (Oct. 9, 2008)

- SCRC Blog: Assessing the impact of U of C African American graduates (Nov. 3, 2008)