Matters of life and debt

Matters of life and debt

In February 2007 the University committed $50 million

to increase graduate-student funding. The promise remains,

but the ends are harder to meet.

By Jason Kelly

Photography by Dan Dry

Sarah Hanson

After a four-hour shift in the Divinity School coffee shop, Sarah Hanson needs a seat and a jolt of caffeine. She flops into a chair and cracks open a Mountain Dew. A cup of coffee holds no appeal, not while she’s brushing fine grounds off her arm, the residue of an afternoon behind the counter.

Hanson, entering her fifth year at the Div School pursuing a master’s in biblical studies, has worked at the café since she enrolled—first as a barista and, for the past two-and-a-half years, as manager. She oversees a staff of 15 to 18 employees during the academic year, earning about $1,200 a month before taxes. Her take-home pay covers rent and groceries, with a little left to put toward repaying student loans.

Two years ago, to balance the job she needs to subsidize the academic work she loves, Hanson became a part-time student. The decision extended her time to degree—which she hopes to complete in December—but it trimmed her education costs in the long run. Tuition assistance from the Div School, along with some merit-based grant money, have helped her fund her education. She has health insurance through the University, which now includes improved prescription coverage that she calls a “godsend.”

Still, Hanson expects to leave Chicago about $25,000 in debt. And she wonders, only half-jokingly, if her most valuable experience, given the stagnant job market, might be in café management.

As a master’s student Hanson does not receive the same funding as doctoral candidates, who benefit from the Graduate Aid Initiative (GAI) that increased stipends in 2007. But Hanson’s “frightening” economic situation reflects a common variable of the graduate-student experience—how the financial realities of everyday life interfere with the life of the mind.

From an economic standpoint, there is no typical path to an advanced degree. Chicago’s decentralized divisions each provide funding differently, and they face specific sets of fiscal issues. Across all fields, students’ personal circumstances create vast differences in their financial needs.

Last spring the group Graduate Students United conducted a cost-of-living survey that illustrated those differences. One student insisted it took only $8,000 a year to make ends meet. Another calculated that it took $40,000. Fifth-year cultural-anthropology student Eli Thorkelson, AM’07, who served on the GSU committee that wrote the survey, lands somewhere in between. “If you scrounge,” he says, “you can live on less than $20,000.”

That’s in line with the University’s official estimate of a graduate student’s annual expense budget—$19,560 for three quarters in 2008–09. There are as many ways to cover expenses as there are areas of study. Fellowships boost some bank accounts, along with other funding designated for research and writing. Teaching, editing papers, or tutoring provide supplemental income for some. Still others work whatever odd jobs they can find. “One of the reasons this survey defies easy summary is that there’s an incredible diversity of ways that graduate students make ends meet,” Thorkelson says, noting responses such as lawn care, babysitting, and waiting tables. The money isn’t just for beer and pizza. Many graduate students have spouses and children but don’t have the steady income necessary to support them. “The financial situation is drastically complicated by the fact that it’s not just a bunch of 20-year-olds with no obligations.”

Paying for graduate school can be complicated even for a heavily subsidized student like Thorkelson. He came to Chicago with a National Science Foundation fellowship worth $30,000 a year. It lasted three years, and the University offered a fourth at the same amount, “which is really a lot of money for a graduate student,” he says. He estimates that more than half of his 23-member anthropology class that entered in 2005 made do with an annual stipend from the University, which varied but then was usually worth about $13,500.

Thorkelson’s four flush years have passed. “This is now the depressing part of the story,” he says with a laugh. Last year his eight field-research grant applications were turned down. Since he left for Paris in June to spend a year studying the politics of French higher education, he has absorbed the decline in income with reserves from his fellowship. “Although the bank account is constantly declining,” Thorkelson says, “it’s not in the red.”

Keeping more students in the black and on track to their degrees is the goal of recent changes to Chicago’s graduate-funding structure. Allocating $50 million over six years for the GAI that began in 2007–08, the University offers most doctoral students in the humanities, social sciences, and the Divinity School increased stipends (now $19,500 per year). Students also receive two $3,000 summer-research grants. For five years, in addition to the stipends, “we pay their tuition and provide them with health care,” says Cathy Cohen, deputy provost for graduate education, with the expectation that they teach in return.

For some students who arrived before the GAI went into effect in the 2007-08 academic year, the additional funding is a source of frustration. The February 2007 announcement that students who were already enrolled would not receive the increased stipends sparked campus protests. It also spurred the formation of Graduate Students United, which now has 250–300 members predominantly representing the humanities and social-science divisions.

In response to recommendations from student committees, Provost Thomas Rosenbaum implemented several changes in 2008 to help pre-GAI students. Raises for graduate-student teachers, stipend increases, and additional fellowships were among the benefits extended to students not funded under the initiative.

Fourth-year history PhD student Toussaint Losier acknowledged the “key improvements” the University made. Still, the former Student Government vice president of student affairs says, “there is concern that there’s a perfect storm brewing” as the first GAI class enters its third year. Losier and other students fear the economic collapse will limit off-campus job opportunities, and that GAI students moving into teaching positions mandated by their funding packages will force current graduate-student teachers out of their positions.

This past May students gathered in front of the Administration Building to raise awareness about the teaching issue. Some carried signs shaped like thumbs—twiddling them, they said, to mimic the administration’s perceived inaction. Cohen tried to assure students that administrators were monitoring the situation to prevent a problem from arising. “We’ve been paying very close attention to the numbers,” she told the Maroon, “so that particular students who have a [teaching] requirement will be able to find a position, and that our new teachers won’t crowd out more advanced graduate students.”

Meeting the financial obligations of students pre- and post-GAI is “a balancing act,” says Humanities Dean Martha Roth. Increasing aid was “the right thing to do,” Roth says, “but it puts enormous pressures on the institution.” The recent economic turmoil has only intensified that pressure.

Because of the recession, academic units campus-wide had to cut their budgets 2.5 to 5 percent, but the deans upheld their financial-aid obligations. That made difficult choices necessary; Roth, for instance, reduced the number of incoming PhD students this fall. The Humanities Division admitted only 75 for 2009–10 instead of the usual 110. With the need for immediate budget cuts, she says, “an obvious area to make a reduction is to bring in fewer students so the future commitment is lessened. Given the economy and the projected job market, I think that’s actually doing a service to our current and recent students, to keep this bulge from going through the pipeline.” Roth expects an admissions increase next year.

Some of the bulge Roth references comes from students on the back end of their PhD work, which often extends years beyond the University’s funding commitment. Roth completed her doctoral work at the University of Pennsylvania in under six years. But in 1979, as now, she was an exception. “For most students in the humanities,” she says, “it can take six, seven, eight years—or more.” Part of her role as dean, Roth believes, is to create a culture that encourages more efficiency from start to finish. Toward that end, the division funds 35–40 dissertation write-ups per year. “My goal,” Roth says, “is to get 100 of these [grants] a year” to help students get out of school faster.

Part of the impetus for the GAI itself was to lessen the need for outside income, so students could finish their degrees earlier. “If a student doesn’t have enough money to pay the rent and ends up taking jobs,” Cohen says, “it can be distracting to the work of passing exams, or the research and writing of their dissertations. We need to make sure they have enough funding to continue their progress.”

Even as the University maintains its increased funding, some students still feel forced to make the best of bad options. “You get to take your pick,” Thorkelson says, “economic turmoil or time-management turmoil.”

Sarah Hanson feels both. Managing the Div School coffee shop pays for necessities, but it takes at least 15–20 hours a week away from her academic responsibilities. It’s not only the time; the hours on her feet weigh on her eyelids. After she closes the café, she sometimes struggles to summon enough energy to study.

Although it might feel like a small consolation when she’s short on time and money, Hanson believes the trade-off is worth it. She is immersed in a subject she loves with a reasonable expectation that an academic career will be available eventually. It’s a goal that requires sacrifices both now and for the foreseeable future.

She takes solace that her education is an investment that cannot be taken away—whether her future is in academia or at Intelligentsia—but her debt feels indelible too. “I try to overpay when I can,” Hanson says, “but sometimes you’re paying like $100 on a $10,000 loan and you think, ‘This is going to haunt me.’”

The cost of College admission

For Liliana Zaragoza, ’10, a Harvard or Columbia education would have meant money in the bank. Both schools offered her more financial aid than the University of Chicago—a full scholarship from Harvard, and almost as much from Columbia. She declined in favor of taking on loans for the “totally masochist, selling-yourself-to-academia vibe” she sensed in Hyde Park. Enrolling in the College would require cobbling together an estimated $45,000–50,000 over four years. “You can’t—well, you can—put a price on it to some extent,” Zaragoza says, “but in the end the educational experience should matter more.”

There were moments of scholar’s remorse the summer before her first year in 2006. Ten students from Zaragoza’s high-school class in Tucson, Arizona, were accepted at Chicago, but only two enrolled. The rest decided they would not—or could not—risk the financial commitment. At times Zaragoza doubted her decision. “Oh my God, what am I doing?” she says. “I’m taking on all these loans when there were two schools that offered to pay for everything. It made me feel guilty at times,” in part because her mother, who’s single and on disability, subsidized some of her education through federal Parent Plus loans. Zaragoza also envisioned an indefinite future of payments and the potential effect on her own children. “I kept hoping it would be worth it.”

Fast-forward two years and $20,000-plus in debt. Zaragoza’s calculation (loans + masochism = educational satisfaction) turned out to be correct. It was worth it. Through her international-studies major Zaragoza has determined that she wants to be an immigration lawyer—not the most lucrative career path, and one that might require additional loans for law school. As with her decision to accept less money to attend the U of C, Zaragoza puts her ideals ahead of potential income. “I don’t think I would have ever gone into a particular area of work just for the money,” she says. Her family counsels her to think about higher-paying jobs to justify the cost of attending Chicago. “My mom would actually talk about it a lot. She didn’t want me to really worry” about the loan burden.

Her academic happiness notwithstanding, Zaragoza understood the economic calculation of attending the College. So when she learned about the new Odyssey scholarship program late in her second year, she hoped it might stem her accumulating debt. An anonymous $100 million donation established Odyssey to reduce or eliminate undergraduate loans, and the University is raising $300 million more to endow it fully.

Zaragoza didn’t know how much she would receive, or if she would even qualify. When her third-year financial-aid package arrived, it informed her that an Odyssey scholarship would eliminate her need for more loans. It was “a massive load off” to find out that she would not have to take on additional debt.

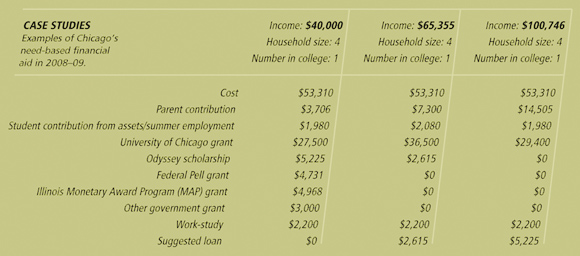

Under its need-blind admissions policy, the College meets the need for all financial-aid applicants. Tuition, room, board, and fees add up to $51,078 for 2009–10, a 3.5 percent increase from last year. Based on a student’s household income and assets, the financial-aid office calculates the package of grants and loans necessary to meet the $54,340 “cost of attendance,” which includes $3,262 for books and expenses.

Depending on a student’s income level, Odyssey scholarships help reduce the need for loans. For a family making $60,000 or less, “we do not expect the student to borrow,” says Alicia Reyes, director of College aid. For incomes of $60,000–$75,000, Odyssey cuts the loan amount in half (see chart).

In 2008–09 the College distributed $59.7 million in need-based financial aid, helping to underwrite the education of one in two undergraduates. “If the student demonstrates a need,” Reyes says, “we will meet it.” After the economic collapse last year, administrators worried about meeting a potential increase in need as parents lost jobs or home equity—all while the University’s own finances took a hit.

Although some parents did report layoffs, reduced income, or dwindling home values that affected how much they could pay, the overall impact of the recession was not as dramatic as administrators had feared. “I’ve seen more parents who are projecting lower income, but not as many as I expected to see losing jobs,” Reyes says. “In the winter, there were discussions about what might happen if we saw a huge surge in the number of appeals, but that didn’t happen. We had maybe ten more than we typically have.” The landscape has changed—including fewer families than usual whose circumstances have changed for the better—but Reyes says the effect is “not huge.”

One student whose situation changed for the worse, Alex Sisto, ’11, awaited word this summer about changes to his financial-aid package. Sisto’s mother lost a job at one of two colleges where she taught art. As a rising third-year, he also plans to move from a dorm into an apartment, which cuts aid by $1,000–$1,500. An Odyssey scholarship reduced his obligation last year, so he didn’t have to apply for the maximum loan allowed under his federal plan. With his mother’s drop in income, he expected to need the full $5,500 available for third- and fourth-year students. Ultimately, with some help from his grandmother and the cost reduction of living off campus, his loan amount came out about the same as last year.

A law, letters, and society major from northwest Indiana, Sisto tries not to dwell on present and future uncertainty. Like Zaragoza, he focuses on the long-term value of his investment. Sisto figures he will owe $15,000–$18,000. “I feel like that’s not bad,” he says, “for not having much money and still going to a high-caliber school.” It’s less than the typical Chicago student in his situation. Almost 40 percent of 2007–08 graduates—the most recent data available—had federal loans; they averaged $19,553 in debt. Nationally, Reyes said, the numbers are poorly reported, making an average difficult to determine. She cited the Project on Student Debt annual report as a good source; its most recent figure for the Class of 2007 was $20,098.

Student contributions to their tuition bills—the self-help portion of the financial-aid calculation—do not necessarily come from loans alone. A federal work-study program has paid for Sisto’s jobs at the Neighborhood Schools Program in a fourth-grade classroom, an after-school program, a summer camp, and a local state representative’s office. He worked full time this summer and typically logs about ten hours a week during the academic year. “It forces me to manage my time better,” Sisto says, along with making his finances manageable.

During Zaragoza’s first two years she worked 15–20 hours a week in jobs on and off campus. Last year, thanks to her Odyssey scholarship, she cut back on her paid hours and took a volunteer job at the National Immigrant Justice Center. She worked more hours overall, but the practical experience confirmed the interest in immigration law that she discovered in the classroom. “I probably just got less sleep,” Zaragoza says. At least she didn’t lose any sleep over the burden of additional debt.—J.K.

WRITE THE EDITOR

DISCUSS THIS ARTICLE

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

MORE FROM THE MAGAZINE

RELATED LINKS

EDITOR’S PICKS

RELATED READING

- "Epic Quest" (University of Chicago Magazine, Sept–Oct/07)