Dream deferred

Joshua Hoyt, AM’95, leads the fight for immigrants’ rights in Illinois.

By Richard Mertens

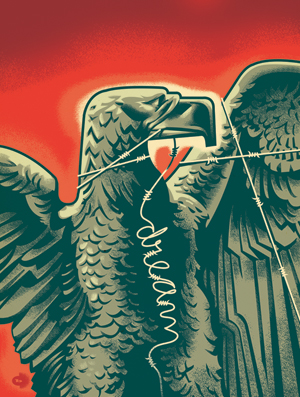

Illustrations by Mark Bender

Joshua Hoyt had a bad feeling. It was a cold Saturday morning in late December 2010, a day of reckoning for Hoyt, AM’95, and many others. After weeks of delay, the US Senate planned to vote on a bill that would offer young illegal immigrants a path to citizenship. As executive director of the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, Hoyt had worked almost a decade on their behalf.

Hoyt sat in his apartment on Chicago’s North Side, watching the vote on CNN. He and other immigration leaders had begun the year lobbying for a comprehensive overhaul of immigration laws to make it possible for the country’s 11 million illegal immigrants to live and work in the United States without fear of deportation and to have the opportunity to become citizens. When that effort went nowhere, advocates shifted their energies to more modest legislation—the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act. The DREAM Act, as it’s known, would offer legal status to an estimated 1.1 million immigrants under the age of 30, many of whom had been spirited across the border by their parents as small children and had spent almost their entire lives in the United States. To qualify for citizenship they would have to finish high school and complete two years of college or military service. The bill was far less than what advocates wanted; still, it was an attempt to win a small victory on behalf of the most sympathetic, and in many ways the most Americanized, of the country’s illegal residents.

The act had already failed several times since it was first introduced in August 2001. But there was reason to hope that this time might be different. President Obama supported the DREAM Act, and polls suggested that most Americans did too. Immigrant-rights groups had been pushing hard for it. Hoyt and the Illinois coalition had organized rallies and other events in support and were working to sway legislators.

At a coalition phone bank, workers spent their days asking Illinois supporters to call their representatives. Hoyt worked his own phone, urging prominent state officials to declare publicly their support for the DREAM Act. Many did, including former Republican governor James Edgar and a dozen university presidents.

Despite these and other efforts, Hoyt was in far from a celebratory mood that Saturday. He knew that, since September 11, 2001, immigration policy had become increasingly caught up in Washington’s partisan warfare. Republicans who once supported the act no longer did, including early sponsors like Senators Orrin Hatch of Utah and John McCain of Arizona. The House of Representatives had passed the DREAM Act ten days before, but there was too much uncertainty to predict the outcome in the Senate, and Hoyt worried that the bill was doomed.

His instincts were right. Although a majority of senators voted to end debate and move the bill to the Senate floor, only three Republicans did—not enough to prevent a filibuster. “Oh, shit,” Hoyt thought as he watched the vote unfold. Then he got in his car and drove west, to the office of the Albany Park Neighborhood Council. About three dozen people, many of them young undocumented Latinos, had gathered in a conference room to watch the voting. When Hoyt arrived some were still sobbing. “They were practically moaning with despair,” he recalls. A few parents and organizers were trying to comfort them. “We weren’t sure,” says 17-year-old Berenice, who had been attending DREAM Act rallies since she was a high-school freshman. “But we had hoped.”

Hoyt spoke to them. Quietly, he acknowledged their disappointment. He spoke of the difficulties they faced, growing up in a country where they could not legally work or get a driver’s license, much less become doctors or teachers or lawyers. But he said that the struggle would go on and that someday they would prevail. “To show us that he cares means a lot to us,” says Berenice (a pseudonym to protect her and her family).

Hoyt is no stranger to difficult campaigns. Schooled in the tradition of Saul Alinsky, PhB’30—the father of modern community organizing—he has worked since the late 1970s as an organizer in some of Chicago’s toughest neighborhoods, battling wily slumlords, cautious politicians, and pretty much anyone else who might threaten his cause. A short, stocky man with glasses and sandy hair tending toward gray, Hoyt combines lofty idealism with political shrewdness and a bulldog temperament. One moment he’s soft-spoken and articulate; the next he’s cursing. After the DREAM Act vote he was especially hard on then-Congressman Mark Kirk of Illinois (now a senator), who had voted against it, calling Kirk a “mean-spirited demagogue.”

Hoyt is “not warm and fuzzy,” says Thomas Lenz, an organizer who worked with him on the North Side two decades ago. “He’s a very blunt and direct kind of guy. ... That’s partly because that’s how you’re going to be effective.”

Under his leadership the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights has thrived. Since Hoyt joined in 2002, the organization has grown in size and influence. It has expanded its reach in downstate Illinois and in the Chicago suburbs, increasing from about 75 to 138 member organizations. Its budget has grown from $1.8 million to $7.9 million, its staff from nine to 25 employees. In nine years he has transformed the group into a powerful advocate for immigrants and a leader among similar organizations around the country.

There have been plenty of defeats along the way. Federal immigration reform has failed repeatedly, and in many ways immigrants face more legal perils than ever. Under Obama, the federal government deports more illegal immigrants than ever—almost 400,000 last fiscal year, inflicting what immigrant-rights advocates say is great suffering on immigrant families. But the coalition has united disparate immigrant groups and helped to bring about policies that make Illinois one of the most immigrant-friendly states in the country. State law allows illegal immigrants to pay in-state tuition at Illinois public colleges and universities, a state-funded program helps immigrants become citizens, and the political climate has discouraged the harsh anti-immigrant policies popular in places like Arizona and Indiana. “Josh clearly has done an amazing job organizing people,” says Sylvia Puente, AM’90, executive director of the Chicago-based Latino Policy Forum. “We’ve never had a more organized immigrant community.”

Hoyt works out of a small office at the coalition’s 20th-floor headquarters in downtown Chicago. “This is the first time I’ve worked in an organization of more than six people and higher than the third floor,” he says. On one wall hangs a framed certificate from the union Unite Here Local 1, commemorating the June day in 2004 when he was arrested in support of striking workers, many of them immigrants, at Chicago’s Congress Hotel (they’re still striking). On the wall opposite his desk is a small collection of portraits including Alinsky and Frederick Douglass. Hoyt says, “I’ve got my angels here.”

Hoyt, 55, has worked as an organizer almost continuously since graduating from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, only once or twice veering toward politics or lapsing into what he calls “straight” employment. He’s spent almost all of that time in Chicago and in Latin America, where he was briefly a lay volunteer for the Catholic Church. His commitment to community organizing reflects both talent and temperament—“I’ve always been good in a fight.” But it also springs from a powerful belief in democracy and an equally powerful indignation toward anyone who would deny it to “the most vulnerable in our community.”

“He’s a man of principle,” says Father Claudio Holzer, an Italian priest who works with immigrants in the largely Latino suburb of Melrose Park, just west of Chicago. “He’s a man of faith. He’s a man of strong will. Second, he’s a man who knows exactly what to do. He knows how to motivate people.”

He has a lot of people to motivate. The coalition’s 138 organizations include a wide range of groups that work with immigrants, from the Access Community Health Network, a private health-care system for the poor, to the Youth Service Bureau of Illinois Valley, a nonprofit agency that serves children in that region, whose old factory towns have attracted many immigrant families. Most coalition members are Latino, the largest immigrant group in Illinois, but many are not. The coalition’s members speak 53 different languages. “It’s a real United Nations,” Hoyt says.

Immigration reform hasn’t been the coalition’s only fight. Early this year its leaders spoke out in support of Muslims trying to build a mosque in the Chicago suburbs. It also provides services to immigrants and works to engage them more fully in civic life. Its member groups help immigrants find health-care services and educational opportunities. Since 2006 the coalition has registered more than 103,000 immigrant voters. It fought for the in-state college-tuition legislation. And since 2005 the coalition has worked with the state to help 47,122 legal immigrants become citizens. This last effort, called the New Americans Initiative, ranks among the group’s most innovative and influential work. Audrey Singer, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, says that cooperating with the state to integrate immigrants into American life was “a really different approach” that has inspired similar programs across the country.

Hoyt grew up in Evanston, north of Chicago, in a middle-class Catholic family of German and Irish ancestry. In 1975 he experienced a political awakening when he spent his junior year of college in Barcelona. On the November night when Francisco Franco died, Hoyt joined demonstrators in the streets protesting against Franco’s regime. The demonstration turned violent when Fascist youth groups, aided by military police, attacked the demonstrators with chains and tire irons. Hoyt escaped unharmed but profoundly shaken. “I’d never had an experience where I was personally terrified of the violence,” he says, “and I had never seen how a dictatorship uses terror to maintain control over people.”

Protests against the government continued that year, and Hoyt was drawn to them. More than once he fled with tear gas stinging his eyes or pursued by police wielding billy clubs. But the moment he remembers most vividly took place in the spring, when the police waded into a huge crowd to break it up. Instead of running, the protestors sat down and refused to move. “It sort of made me understand that through people acting, and acting together, you can make a country a better place.”

After college, Hoyt got his first job as an organizer, working for United Neighbors in Action in Humboldt Park, a Puerto Rican neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side. He had just started and was trying to organize a block club meeting when, on June 4, 1977, a riot broke out during a Puerto Rican Day celebration. The Chicago police shot and killed two men; another died in a fire set by rioters. Later Hoyt was beaten up when he strayed into an unfamiliar neighborhood. “It was the worst year of my life, but it was also transformational,” he says. “Up till then my knowledge of organizing was very intellectual. There I got to know the people.” He spent much of the year helping local residents fight slumlords and trying to get rid of abandoned buildings. He picked up some tricks of the organizing business, as when he led residents out to the suburbs to protest at the home of an especially uncooperative landlord. He learned a lot from Shel Trapp, a founder of United Neighbors in Action’s parent organization and a Methodist minister whose mottoes included “blessed be the fighters.” Hoyt considered Trapp a “brilliant organizer.”

“He was completely unafraid of conflict,” he says, “completely unafraid of challenging people.”

In 1979 Hoyt traveled to Peru, where he worked in the highlands for the Catholic Church. He took part in several campaigns, most of which failed. In one, subsistence farmers fought with big landowners over the right to farm communal land. (Hoyt helped the farmers plan land seizures.) He also helped a small town oppose a plan to divert water used for local corn, potatoes, and other crops to wash gravel for concrete for a World Bank hydroelectric project. The campaign culminated in an angry confrontation, with police wielding machine guns, women throwing gravel, men trying to overturn the local police chief’s car, and Hoyt in his poncho trying to look small. His side won once, when the residents of several small towns demanded an end to a bus-transportation monopoly. Hoyt helped gather petitions and stage a rally that drew 10,000 people. “It felt pretty good,” he says.

Hoyt’s time in Peru strengthened his ties to Latin America. Yet, he says, “I felt I didn’t belong there.” He belonged in Chicago. Back home he worked for a series of community organizations, including Erie Neighborhood House, one of Chicago’s old settlement houses, and the Pilsen Neighbors Community Council. In 1982 he began studying toward a master’s degree in Latin American studies at the University of Chicago. “I didn’t want my mind to atrophy,” he says. He dabbled in politics, campaigning for Mayor Harold Washington in 1983 and 1987. In 1985 he filed as a candidate for state representative, but he dropped out when an Asian American woman entered the race. “I felt if Asians wanted to run a candidate, to gain political power, I shouldn’t stand in their way,” he says. He’s since concluded that he would have made a poor politician anyway (“I have too much of a temper”). From 1985 to 1987 he wrote reports on community banking issues for the Woodstock Institute, an Illinois think tank.

Mostly he stuck to organizing. In 1987 he joined the Organization of the North East, known as ONE, a community group on Chicago’s North Side that worked on affordable housing and education issues but was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. By recruiting new allies, including business owners and ethnic associations, Hoyt “pretty much turned ONE around,” says Lenz, who worked with Hoyt at the time.

In 1997 Hoyt helped start United Power for Action and Justice, an ambitious coalition of community groups and religious organizations from across the Chicago region. The aim of United Power was to take the city’s organizing to a new level of coordination and influence by reaching across racial, ethnic, religious, and geographic lines. But Chicago was too diverse, too tribal, for such an organization to work at the level its founders envisioned. Hoyt says, “It didn’t become what we hoped it would become.”

An organizer is more than an activist. An activist can freelance; the job of an organizer is to build groups, institutions, and relationships around issues of common concern. At the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, Hoyt’s job is not so much to fight for immigrant issues as to help other people fight. He has done this in part by helping them mobilize politically. “I think we did some of that before Josh was here; I’m not sure we did it very well,” says Juan Salgado, president and CEO of Chicago’s Instituto del Progreso Latino who served for six years as chair of the coalition’s board of directors. “There was no political program. We weren’t doing voter registration. We weren’t relating to communities at the level we are now.”

Hoyt also has encouraged an old-school Chicago toughness. “We’re the land of the good old-fashioned, get-down-in-the-gutter, kick-and-scratch and bite-and-claw, precinct-level ethnic politics,” he told a group in New York three years ago. “We’ve learned from the best. We’ve learned what you’ve got to do is you’ve got to take numbers and translate them into political power. You’ve got to translate them into the ability to reward your friends and punish your enemies.”

He can be almost as hard on his friends. Last year, for example, some supporters thought he went too far in encouraging sharp criticism of Senator Richard Durbin, an Illinois Democrat and a cosponsor of the DREAM Act. The “dust-up,” as Hoyt calls it, started in 2009, when Hoyt was among those trying to stop the deportation of Rigoberto Padilla, an undocumented honor student at the University of Illinois at Chicago who had gotten in trouble with immigration authorities after being charged with drunk driving. They had “run into a brick wall” with Durbin, Hoyt says, so in October he, Padilla, and a small group of supporters ambushed the senator outside a DePaul University building where Durbin was scheduled to speak on immigration reform. As Durbin emerged from his car, Hoyt’s group demanded to know what he would do to help Padilla. (In December 2009 the Department of Homeland Security agreed to defer Padilla’s deportation.) In early 2010 Hoyt and the coalition also launched a “Change Takes Courage” campaign that accused both Durbin and Obama of excessive caution on immigration reform.

Not everyone in the coalition is comfortable with the tactics of confrontation. “It’s been very challenging,” says Tuyet Le, executive director of Chicago’s Asian American Institute. “I think we’re learning a lot, but we have to do it in our own way and [at our] own pace. I think he’s trying to move us along at his speed.”

Before February’s mayoral election in Chicago, Le and other Asian American leaders organized a candidate forum. Rahm Emanuel, the eventual winner, declined to attend. After much agonizing, and at Hoyt’s urging, Le says, she sent out a press release criticizing Emanuel—making a “big deal out of it”—in a way she would not have done before. “I got a lot of calls from people when we sent that out. They were uncomfortable. They said, ‘I’m not sure we should do that.’” She told them that Asian Americans had tried for too long to be nice.

Hoyt has put much effort into developing leaders among the coalition’s immigrant groups, often by pushing them to do what does not come naturally to them. Salgado, who considers himself reserved and cautious, says Hoyt has challenged him to be more assertive, sometimes by appointing him “closer” at meetings with elected officials, a job that requires him to sum up forcefully the coalition’s demands.

Hoyt also has taught him the art of public ridicule. Several years ago, Salgado recalls, Hoyt urged them to hit Democratic US Representative Dan Lipinski “hard in the press” after his vote on an immigration bill. The challenge was to do it in a way that would attract media attention. Hoyt wanted to embarrass Lipinski by comparing him unfavorably to his better-known father, longtime Congressman Bill Lipinski, who had held the seat before him. “Josh came up with the whole thing,” Salgado says. “He called it ‘the Lesser Lip, the Puppet Prince of the Southwest Side.’” Salgado’s job was to deliver this message at a rally outside Lipinski’s Chicago-area office. He didn’t want to. “I said, ‘I don’t have a problem with hitting him. But let’s keep it civil.’” Hoyt retorted: Look what Lipinski has done to the immigrant community. So Salgado went along. “We got the press,” Salgado says. “He was right.”

Hoyt has also trained and mentored many young people who have gone on to work elsewhere in the immigrant-rights movement, including some from the University of Chicago. Marissa Graciosa, AB’02, the daughter of Filipino immigrants, joined the coalition in 2003. Three days after she started, Hoyt made her run a press conference. “It was trial by fire,” she says. She spent four years at the coalition, including two as its political director, and now directs the national Fair Immigration Reform Movement. “Basically we are now leaders in our own struggle,” she says. “Before, it was mostly white DC advocates. It’s really significant, the leadership that’s come out of ICIRR. And I think that’s because of Josh.”

In February 2010 the University’s Latin American studies program invited Hoyt to address a small audience of mainly graduate students. He talked about immigration reform and answered questions. But when he asked for volunteers to help with the coalition’s work, no one offered. “Well, fuck you,” he said. “I’m not here to subsidize your education.” Then he sat down. The audience was stunned. Soon Hoyt resumed talking, explaining that the coalition was organizing busloads of supporters to attend an immigration rally in Washington. Couldn’t they organize a bus from the University of Chicago? A few students finally stepped forward. They recruited other students and raised money, in part by selling tamales outside Cobb Hall. In the end they sent 24 University students to the March 21 rally and started a new campus group called University of Chicago Coalition for Immigrant Rights.

One of the students who volunteered that evening, and helped to sell the tamales, was a 22-year-old undergraduate, Diana. Diana (a pseudonym used to protect her family from immigration authorities) is an undocumented student whose life was transformed by that encounter last February. Born in Mexico City, she crossed the border into the United States when she was three; her parents won’t tell her how or where. She excelled in school and, thanks to an alumni scholarship for students from Chicago Public Schools, was able to attend the University.

She found it difficult to adjust to life at the U of C. She didn’t feel she fit in. She didn’t know anyone else who was undocumented, and she was afraid to speak of it. “I was ashamed of my birthplace,” Diana told a group of fellow undocumented students at a rally this winter at Chicago’s Daley Plaza. “I was afraid of what would happen. I would cry at night because I felt I was no one.” While classmates talked about jobs and internships, she kept quiet. She had no idea what she would do—what she could do—after graduation.

Lately she has thrown herself into the immigrant-rights movement. She has taken part in meetings with public officials such as Durbin and state senator Bill Brady. Last May she organized a vigil in front of Obama’s Kenwood house to protest deportations. In October she was one of three students who sat for six hours in Kirk’s Senate campaign office, demanding a meeting (they didn’t get one).

Working for the coalition has boosted Diana’s confidence. “It’s been empowering,” she says. “I really feel I can do things.” When she first volunteered for the coalition, she found Hoyt intimidating. Like many immigrants, she also wondered why a nonimmigrant, and a non-Latino at that, was leading the state’s largest immigrant-rights group. But she’s grown to admire him. “He really is passionate,” she says. “He cares a lot about the issues.”

Others are more critical. “He’s kind of a bully type,” says Oscar Chacon, executive director of the Chicago-based National Alliance of Latin American and Caribbean Communities. More broadly, Chacon says that Hoyt and the immigrant-rights movement have been unwilling to rethink their strategy. “He’s been a leader of what has been for all practical purposes a failure in getting comprehensive immigration reform,” Chacon says. The coalition, Chacon believes, has been too concerned with registering voters and not enough with giving them a reason to vote. “Our real problem,” he says, “is turning out the vote.”

Some in the immigrant community question Hoyt’s strategy to focus early last year on comprehensive immigration reform even when its prospects were dim. Instead of attacking Obama for his diffidence on the issue, they argue, Hoyt and other leaders should have shifted their attention sooner to passing the more popular DREAM Act.

“A lot of us were really angry,” says Tania Unzueta, a 27-year-old undocumented graduate student at the University of Illinois at Chicago and a founder of the Immigrant Youth Justice League. “A lot of us felt that if we had spent more resources at the beginning of the year on the DREAM Act, it might have passed.”

The act’s defeat, like the Republican sweep in the November elections, dealt a heavy blow to the hopes of immigrants and their advocates. (In April Durbin announced he would introduce the DREAM Act again this year.) But in Hoyt’s mind the failure of immigration reform did nothing to invalidate the coalition’s core strategy of registering voters and helping legal immigrants become citizens. The more immigrants who become citizens and voters, he reasons, the harder it will be for politicians to ignore their interests. “The thing I’m proudest of is the long, hard, slow work going into changing the political equation in Illinois,” he says. He believes that time—and history—are on his side. To him, organizing immigrants is simply one part of the larger ongoing struggle to fulfill the promise of American democracy.

“We can’t have a democracy where 11 million people are frozen in third-class status and with their families vulnerable to being deported any moment,” he says. “We benefit from their work. They clean our floors, serve our tables, and yet we won’t invite them to the table of our democracy. The only way immigrants have become full members of our democracy is to fight to get to the table.”

In recent months the coalition’s focus has shifted in part to deportations. Hoyt and Illinois Congressman Luis Gutierrez, one of the main champions of immigration reform, called on Obama to halt deportations (he didn’t). In mid-January more than 260 people from around the region packed a Melrose Park church basement for a coalition workshop on how to fight deportations (don’t open the door if immigration agents come knocking—unless they have a warrant).

The failure of immigration reform did inspire some new ideas. Advocates in Illinois and elsewhere have promoted smaller state versions of the DREAM Act that would help young undocumented immigrants get driver’s licenses and improve their access to private scholarships. Meanwhile the coalition has started a new program, called Neighbor to Neighbor, that enlists nonimmigrant volunteers to teach immigrants English. The aim is not just to improve language skills but also to build connections between immigrants and nonimmigrants and to bridge the cultural divide that has made immigration reform so difficult. “The culture has to change,” Hoyt says. By midwinter the program was underway at three Chicago sites.

But Hoyt has a grander vision: organizers fanning across the state, recruiting as many as 5,000 volunteers. He’s done the math. “If each volunteer works with five immigrants, that’s 25,000,” he says, sitting in his office late one winter evening. “So you do that for ten years. What is that going to do to the culture? That’s what we’re going to build.”