The University of Chicago Magazine

October 1997

A new master's program in the humanities takes as its subject the big questions-and the heated battles those questions often start.

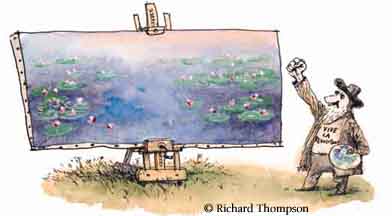

By Jenny Adams Illustrations by Richard Thompson

Christie O'Brien Tate: "I have read bell hooks and others who say that art is politics when I look at Monet's water lilies, I can't perceive the politics of it."

Alice Swan: "Because the water lilies have been around for a while, people tend to forget how revolutionary they were. Monet challenged the way that artists had been looking at the world. What he was trying to depict in his water lilies was the way the world looks reflected in the surface of his water lily pond."

Gerald Graff: "Alice points out that in the context of 19th-century Parisian art wars, painting water lilies in the way Monet and other Impressionists did constituted a political statement against the official academic authorities who controlled the definition of what would count as 'art' and non-art. Alice suggests too that the counterdiscourse of water lilies in this case not only scored political points within the art world, but challenged the way of looking at the world that governed bourgeois culture. Again, though, I want to underscore that to say 'Art is political' is not to give a reason why that fact should necessarily have a privileged role in discussions of art, or why it should even have to be mentioned, given the fact that there is an infinity of other things that all art (or all everything) is, as well."

As last year's fall term came to a close, the e-mail debates waged by members of the new Master of Arts Program in the Humanities (MAPH) had just begun.

Is art inherently political? How does one distinguish between "high" and "low" art? Is art a reflection of human essence, or is humanity secondary? Then again, is "humanity" an artificially constructed category?

For the program's director, English and education professor Gerald Graff, AB'59, the debates signaled success. Whether on e-mail or in the classroom, such debates, Graff believes, are vital to a humanities education and to a program designed explicitly to give students a "larger sense of the issues, conflicts, and debates that define the humanities today."

Modeled on MAPSS, the University's 59-year-old Master of Arts Program in Social Sciences, the 1-year-old MAPH program encompasses the full range of humanities disciplines, requiring students to take one core class but allowing them to structure their own courses of study. Students in the yearlong program-which offers a terminal master's degree-can take any course in the Humanities Division and, in some cases, courses in other University divisions.

The open structure reflects the program's goals. Rather than training students in one field, MAPH teaches them to think and write critically about broad questions in the humanities. "We like to think that the program could become important not just as a good program in itself," Graff says, "but as a new model of graduate study, a form of graduate study that is more oriented toward producing generalists rather than specialists talking to other specialists." He pauses. "And also a form of graduate study that is more adaptable to other kinds of work than graduate teaching."

In fact, MAPH seems to be on the leading edge of a national trend in higher education, with master's programs in the humanities emerging at such schools as Stanford and New York Universities. In part, Chicago's MAPH has its roots in the English department, which for years admitted large numbers of students at the master's level, forcing them into a one-year, sometimes cutthroat competition for admission to the Ph.D. program: From an incoming master's class of 40 students, only 15 or so would be invited to stay on.

This system-which created bad student-student relations as well as bad student-faculty ones-dissatisfied all involved and led to MAPH's creation. The English department now admits a smaller number of people to its master's programs, transferring many applications to MAPH, which adds them to its own pool of applicants before making offers of admission.

Though MAPH could have been viewed as a lesser substitute, its directors were determined to make it an equally strong alternative. Lawrence Rothfield, the program's co-director and associate dean of humanities, explains, "We wanted to make the program into a positive experience, in part by defining more clearly what it is that one wants to get out of an M.A. in humanities, and in part by giving students more control over what they want to study."

Last year, for example, one student who wanted to study Japanese culture, politics, business, and literature put together a series of courses that spanned six departments and three divisions. Another, fascinated by literary references to medicine, took two courses in the Biological Sciences Division. This year, optional winter quarter core classes include one on visual culture with W. J. T. Mitchell and one on psychoanalytic interpretation, taught by Sander Gilman and Françoise Meltzer. English professor emeritus Wayne Booth, AM'47, PhD'50, who taught a course on irony last year, will this year give a class on the rhetorics of religions.

For students who do plan to continue graduate work, the generalist approach provides a broad foundation for more specialized studies. For those who choose other career paths, the emphasis on critical thinking and clear writing should also prove helpful. To help students make the transition from humanities courses to the working world, the program has set up paid internships with corporations. Last year, MAPH placed students with the investment-banking firm John Nuveen & Co., and with Leo Shapiro and Associates, a survey research firm (Shapiro, AB'42, earned his Ph.D. in sociology from Chicago in 1956). This year, Graff and Rothfield hope to expand the internships to include publishing houses and secondary schools.

Although the program gives students free rein with their course schedules, everyone is required to take its core course, an introduction to some of the day's most heated humanities debates. Enter Jerry Graff.

Faced with a widening lacuna between traditional literary scholars and postmodern theorists, Graff has refused to choose sides. Instead, he has made the debate itself an object of study and the center of his own scholarly work. His 1992 book, Beyond the Culture Wars: How Teaching the Conflicts Can Revitalize American Education, addresses the tensions between the academy and the press, between multiculturalists and traditionalists, and between feuding critical schools, each one declaring its own exclusive claim on truth. That direct address, he believes, is vital: "In the absence of continuous public discussion and debate, doctrines harden and paranoid myths proliferate-like the myth that The Color Purple is replacing Shakespeare, or that new academic theories are attempts to destroy Western civilization."

Thus, debate is a central feature of the "core" course, appropriately titled "The Humanities: Visions, Revisions, and Contested Issues." Team taught by Graff, assistant art professor Laura Letinsky, and associate English professor Lisa Ruddick, the class features regular debate among faculty members. The course repeatedly asks students to question the status of literature and to analyze the semantics of the current debates about literature's place in a university's curriculum. Graff encourages students to go behind the arguments, to see what may have caused them in the first place. Students are expected to continue the discussions outside of class by posting to an e-mail list.

Set up as a series of case studies, each unit of the quarter-long core course presents a contested issue in subject areas ranging from literature to visual culture, from queer theory to anthropology. The e-mail debate about art, for example, grew out of a two-week unit that examined photography and visual culture. Later in the year, when students are busily taking courses in all corners of the Humanities Division, the core course serves as a touchstone when they inevitably revisit some of the issues they encountered in the fall.

Rothfield, who helped design the course, sees a natural connection between it and Graff's theories. Andrew P. Hoberek, AM'90, the program's assistant director, agrees that the course is indeed "Graffian": "It raises the question of how and why one does this work, rather than familiarizing people with a given archive of knowledge." But Graff shies away from a direct connection: "Any program of this kind has to represent a lot of people who might not agree with my agenda-or even know about it. I think the program can't just institutionalize the vision of a single person." A very Graffian response.