|

|

|

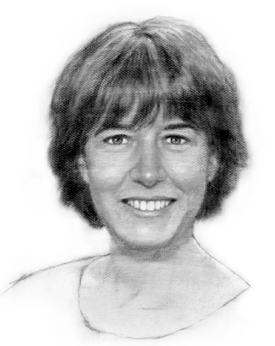

Rockefeller at 75 The Reverend Alison Boden, ordained in the United Church of Christ, is in her second five-year term as dean of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel. Since her 1995 arrival she’s increased Sunday worship attendance, local preacher visits, study groups, and neighborhood programs. Her Divinity School and College classes focus on preparing students for the ministry and on human rights and religion. For Rockefeller’s anniversary year she helped to create a March 1–June 18 exhibit at the Special Collections Research Center, “Life of the Spirit, Life of the Mind: Rockefeller Memorial Chapel at 75.”

Previously Boden served as Bucknell University’s chaplain and as Union College’s Protestant chaplain. She earned a doctorate from Britain’s University of Bradford in 2003 and a Master of Divinity from New York’s Union Theological Seminary in 1990. Her 1984 Vassar College bachelor’s degree is in drama: “I was an actress in New York City before going to seminary.” What are your biggest short- and long-term goals for Rockefeller? My goals fall into several overlapping categories. The first is programmatic: to increase our historically high-quality musical offerings—our choir, organ, and carillon programs, plus outside artists. I also hope to increase the number of programs—lectures, concerts, travel seminars, discussion groups—that appeal to and bring together members of various religious communities. The second goal is worshipful: to enable and expand all of the religious communities at the University and to deepen the chapel’s own worship-based offerings, including our ecumenical Christian services on Sunday mornings and our interfaith gatherings at other times of the year. The third goal is to restore the chapel building and its instruments, all of which need significant repairs after 75 years of use. The original 1928 Skinner organ, for example, needs some $2 million in repairs and endowment, and the carillon needs another $500,000. Both the carillon and organ are extremely significant instruments, not just on campus but nationally and even internationally. Why are academic rites held at Rockefeller, and how does your role as dean serve them? The first reason that such secular events are held here is simply that the chapel has the largest seating capacity on campus. The second reason is that the University has long sought, rightfully, to wed something “eternal” to its most important events, the ones that it knows point to something beyond the mundane. Many of the great moments of transition that we have as a community—convocations, white-coat ceremonies, hoodings, weddings, memorial services, military commissionings, significant lectures, moments of artistic endeavor—happen here. I hope that, as dean, my participation in some of these events helps to enhance the idea that what we are doing has the deepest value and testifies to our greatest hopes for ourselves: that we should be healers, that we should be enablers of justice, that we should be, collectively, a place where the most profound questions of our corporate life are examined. Although John D. Rockefeller was a Baptist, the cathedral has a somewhat secular feel, with abstract stained glass. Does the chapel consciously try to be non- or multidenominational? In recent months I’ve studied the documents concerning the chapel’s founding and design. What strikes me is how forward-thinking its builders were. They knew, in the 1910s and ’20s, that the University was going to become a more multireligious place, so they built a chapel that was relatively lacking in religious imagery. They wanted it to be accessible to as many people as possible. They also wanted it to be as grand and as architecturally appropriate as the great cathedrals of Europe. In fact, President Ernest DeWitt Burton went to Europe to study those cathedrals to make sure that the University’s would be comparable. In its early years the chapel boldly was intended to be interdenominational Christian, and those who have served on the chapel staff have tried to make it more multireligious, in keeping with the changing religious make-up of the University. We’ve had programs such as concerts of Jewish sacred song, a performance by the University’s Indonesian gamelan with shadow puppets, and the construction of a Tibetan Buddhist sand mandala. The University’s Buddhist organization currently meets for meditation in the chapel, and at one time the Muslim student organization used the chapel for its Friday prayers. When will the Muslim prayer space in Rockefeller’s basement be ready? The Muslim prayer space will come about next fall, when the new Inter-Religious Center opens in the chapel’s basement. That whole basement space will be renovated to permit dedicated prayer rooms for our Muslim and Hindu communities—two of our larger groups that, to date, don’t own their own housing. There will be three other rooms available for all other religious groups to use as they need. How do you appeal to a predominantly young audience? Is Rockefeller part of the larger nationwide trend of alternative worship programs? Not at all. On Sunday mornings we offer a quite traditional Christian service, liturgically. The theology of these services is progressive, inclusive, and interdenominational Christian, but the form is not alternative. As the saying goes, “the architecture always wins.” We are working with an architecture of gravitas. We use the liturgical and theological traditions that we have received to speak to very contemporary questions and challenges—we think the traditions are that elastic and that relevant. Have you noticed an increase or decrease of interest in organized religion? We are in the midst of an ongoing national increase in religious participation. I suspect that this is a pendulum-theory kind of thing—that we are still on the upswing of a great renewal of interest in things religious, and that this upswing will eventually turn downward. Meanwhile, though, we continue to see greater and greater interest in formal religious participation. Students raised by parents who once left religious communities are now interested in engaging such communities themselves as young adults. Other students raised in the bosom of particular religious communities are interested in what others might have to teach them. The lines of religious identification are shifting, which “should” be a time of religious uncertainty, but these are also times of religious growth and intensification. At Chicago there is both shift and growth, and so the demographic lines of religious participation are hardly clearly drawn, but very much on the upswing.

|

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu