The

Business of Reflection

>>

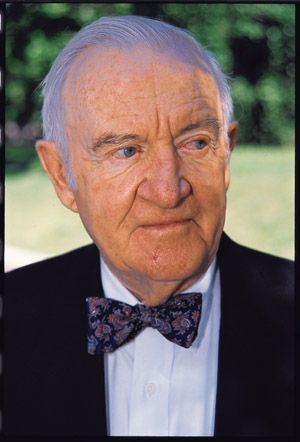

In

awarding its 2002 Alumni Medal to John Paul Stevens, the Alumni Association honored

a Supreme Court Justice with-out an agenda but-as his former law clerk argues-a

Chicago frame of mind.

At

a June 1 ceremony in Rockefeller Chapel, John Paul Stevens, AB'41, received the

Alumni Medal, the highest honor given by the University's alumni association.

Later that day he was also recognized with the Laboratory Schools' Distinguished

Alumnus Award. The two awards are fitting tributes, not only because Stevens-an

Associate Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court since 1975-has had a legal career

that is as distinguished as they come, but also because Stevens is a true son

of the University community. He grew up near the corner of 57th and Kenwood and

in many ways is an intellectual heir of the Lab Schools' founder, John Dewey.

At

a June 1 ceremony in Rockefeller Chapel, John Paul Stevens, AB'41, received the

Alumni Medal, the highest honor given by the University's alumni association.

Later that day he was also recognized with the Laboratory Schools' Distinguished

Alumnus Award. The two awards are fitting tributes, not only because Stevens-an

Associate Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court since 1975-has had a legal career

that is as distinguished as they come, but also because Stevens is a true son

of the University community. He grew up near the corner of 57th and Kenwood and

in many ways is an intellectual heir of the Lab Schools' founder, John Dewey.

In

1932, when Stevens was 12 years old, Dewey wrote: "The business of reflection

in determining the true good cannot be done once and for all, as, for instance,

making out a table of values arranged in a hierarchical order of higher and lower.

It needs to be done, and done over and over and over again, in terms of the conditions

of concrete situations as they arise. In short, the need for reflection and insight

is perpetually recurring." Dewey's concept of "reflection"-the

constant reexamination of one's ideas about the good in concrete situations-provides

a proper description of Stevens's pragmatic judicial philosophy. In his 27 years

on the Court, Stevens has consistently eschewed "once and for all" approaches

to legal problems and has remained attuned to the complexities of individual cases.

He has resisted attempts to categorize legal questions into a hierarchy of levels

of scrutiny and believes that legal rules should be tested against the messy facts

of real-world scenarios. His opinions display the markings of a justice without

an agenda, who takes seriously the idea that the Court should decide one case

at a time as narrowly as possible.

But

Stevens's path to the law was far from certain. As his College graduation approached

in winter 1941, he imagined he would become an English professor. He had studied

poetry with Norman Maclean, PhD'40, and wanted to continue studying Shakespeare

in graduate school. Shortly before graduation, however, a professor who had observed

Stevens's talents in math suggested that he enroll in a correspondence course

in cryptography offered by the Navy. Stevens soon was offered a commission in

Naval Intelligence and joined the Navy on December 6, 1941. While serving as a

code breaker in the Pacific, Stevens received a letter from his older brother,

a 1938 graduate of the Law School. The letter conveyed a yeoman lawyer's excitement

at helping his clients with their problems and serving the public interest.

In

a speech to the Chicago Bar Association last fall, Stevens said that he was reminded

of his brother's enthusiasm for the practice of law when reading an excerpt of

a letter from another newly minted lawyer in David McCullough's recent biography

of John Adams. In the letter Adams writes: "Now to what higher object, to

what greater character, can any mortal aspire than to be possessed of all this

knowledge, well digested and ready at command, to assist the feeble and friendless,

to discountenance the haughty and lawless, to procure redress to wrongs, the advancement

of right, to assert and maintain liberty and virtue, to discourage and abolish

tyranny and vice?"

Animated

by the spirit of public service evoked in his brother's letter, after leaving

the military Stevens enrolled at Northwestern University Law School. There he

quickly distinguished himself-completing his studies in two years, serving as

editor-in-chief of the law review, and graduating first in his class with the

highest grade point average in the school's history. After clerking for Supreme

Court Justice Wiley Rutledge during the 1947 Term, Stevens returned to Chicago

and entered private practice. He soon developed an expertise in antitrust law

and was asked by then-U of C Law School Dean Edward Levi, PhB'32, JD'35, to teach

a course in competition and monopoly. Stevens became one of the early experimenters

in teaching law from an interdisciplinary perspective, co-teaching the course

with economist Aaron Director. Stevens and Levi formed a life-long friendship

that continued in Washington while Levi was serving as Attorney General under

President Ford and Stevens became Ford's only appointee to the Supreme Court.

A recent book, Illinois Justice: The Scandal of 1969 and the Rise of John Paul

Stevens, describes his ascent from young attorney to the post of chief counsel

for the independent commission investigating allegations of misconduct by members

of the Illinois Supreme Court. That was followed by his appointment to the Seventh

Circuit Court of Appeals, and then, five years later, his appointment to the Supreme

Court.

Stevens

has just completed his 27th term on the Court and shows no signs of slowing down.

For the past eight terms he has been the senior associate justice, which means

that whenever he is on the opposite side of a decision from Chief Justice William

Rehnquist (i.e., most of the time), he assigns either the opinion for the Court

or the dissent. During much of his time on the Court, Stevens has been its most

prolific writer and its most frequent dissenter. (The statistics show that he

agrees most often with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg or Justice Stephen Breyer,

and least often with Justice Antonin Scalia.) In the last three terms he has written

almost twice as many dissents as the next most frequent dissenter. Stevens gives

several reasons for this practice of writing separately. The best way to ensure

that he is certain of his vote in a case, he says, is to write out his position.

He also believes strongly in transparency of government and that the Court should

not be immune from public scrutiny. He is critical of the practice of displaying

a false unanimity and thinks the public should know when there is disagreement

among the Justices.

A

steady source of those dissenting opinions has been the Rehnquist Court's decisions

in the area of state sovereign immunity. Stevens has regularly rejected the Court's

unrestrained states' rights jurisprudence, criticizing the doctrine as not only

unmoored from constitutional text, but inconsistent with the demands of modern

governance. In Printz v. United States, a 1997 decision holding that Congress

cannot require local law enforcement officers to conduct background checks of

prospective handgun purchasers, Stevens wrote a dissent that has proved eerily

prophetic:

Indeed,

since the ultimate issue is one of power, we must consider its implications in

times of national emergency. Matters such as the enlistment of air raid wardens,

the administration of a military draft, the mass inoculation of children to forestall

an epidemic, or perhaps the threat of an international terrorist, may require

a national response before federal personnel can be made available to respond.

If the Constitution empowers Congress and the President to make an appropriate

response, is there anything in the Tenth Amendment, "in historical understanding

and practice, in the structure of the Constitution, [or] in the jurisprudence

of this Court,"…that forbids the enlistment of state officers to make

that response effective?

That

pragmatic approach may prove well-suited for a post-September 11world.

These

days Stevens is perhaps best known for his dissenting opinion in Bush v. Gore,

with its powerful ending: "Although we may never know with complete certainty

the identity of the winner of this year's Presidential election, the identity

of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation's confidence in the judge as

an impartial guardian of the rule of law." But he has authored numerous landmark

decisions, such as his opinion this term in Atkins v. Virginia, holding

that the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment bars

the execution of the mentally retarded; Clinton v. Jones, in which he wrote

for a unanimous Court that the President of the United States is not immune from

being sued while in office; and Reno v. ACLU, striking down Congress' first

attempt to regulate pornography on the Internet.

If

those cases come most readily to the public's mind, the lawyer's choice for Stevens's

most significant contribution is most likely Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense

Council, in which the Court recognized that administrative agencies are entitled

to deference when filling in the gaps left by Congress in federal statutes. Not

only is that decision one of the most frequently cited in subsequent cases and

law review articles, but it also has had a major impact on the interaction of

the courts, Congress, and administrative agencies. The decision is typical of

Stevens's approach in recognizing that agencies have an expertise in their particular

sphere, which makes them uniquely suited to develop a regulatory scheme over time,

and that the Court can act as an effective referee in determining when Congress

has implicitly delegated its authority to the Executive branch.

Generally

skeptical of sweeping rules and rigid categories, Stevens often has resisted the

Court's practice in both First Amendment and equal protection cases of categorizing

questions according to different levels of scrutiny. Even though he is one of

the justices most protective of free-speech rights, he does not shy away from

recognizing that not all speech is of equal value. In Texas v. Johnson,

for example, Stevens defied categorization as a sure vote for the free-speech

crowd by writing a passionate dissent against flag burning: "The ideas of

liberty and equality have been an irresistible force in motivating leaders like

Patrick Henry, Susan B. Anthony, and Abraham Lincoln, schoolteachers like Nathan

Hale and Booker T. Washington, the Philippine Scouts who fought at Bataan, and

the soldiers who scaled the bluff at Omaha Beach. If those ideas are worth fighting

for-and our history demonstrates that they are-it cannot be true that the flag

that uniquely symbolizes their power is not itself worthy of protection from unnecessary

desecration." Moreover, he believes that not all fora for expression should

be treated the same-radio broadcasts are different from Web sites, which in turn

are different from public parks. And he is realistic about the fact that bright-line

rules are easily abandoned when tested, noting that categorical rules are "only

'categorical' for a page or two in the U. S. Reports."

Some

of Stevens's most important contributions, however, have been the least publicly

recognized ones. To name just a few, by opting out of the "cert pool,"

which the other Justices use to divide up responsibility for evaluating petitions

for review by the Court, Stevens provides an invaluable check on the system by

which the Court exercises discretion over its docket. By reminding the Court that

its wholesale rejection of legislative history is a relatively recent phenomenon

that often yields results at odds with any sensible notion of what Congress intended,

Stevens preserves a common-sense method of statutory interpretation that views

the Court as a partner with the other branches of government. And his courteous

manner during oral argument offers an example of a genteel professional ethic

that, at times, unfortunately seems a relic of a bygone era.

Despite

his busy schedule on the Court, Stevens has never abandoned his love for literature.

There is a part of the jurist that still wants to be an English professor. He

continues to pursue his love for Shakespeare, choosing to celebrate the end of

the Term this year by visiting the nearby Folger Shakespeare Library. But always

the iconoclast, Stevens is not content to accept the received wisdom with respect

to the authorship of Shakespeare's works. He is part of that small but growing

group of scholars who contend that Edward de Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford,

is the true author of the Shakespeare Canon.

In

awarding Stevens the Alumni Medal, the Alumni Association has recognized that

he embodies the best the University has to offer: "reflection on the true

good," commitment to public service, and independent thinking.

Ed

Siskel, JD'00, is an associate at a law firm in Washington, D.C. He clerked for

Justice Stevens during the October Term 2000.

![]()

At

a June 1 ceremony in Rockefeller Chapel, John Paul Stevens, AB'41, received the

Alumni Medal, the highest honor given by the University's alumni association.

Later that day he was also recognized with the Laboratory Schools' Distinguished

Alumnus Award. The two awards are fitting tributes, not only because Stevens-an

Associate Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court since 1975-has had a legal career

that is as distinguished as they come, but also because Stevens is a true son

of the University community. He grew up near the corner of 57th and Kenwood and

in many ways is an intellectual heir of the Lab Schools' founder, John Dewey.

At

a June 1 ceremony in Rockefeller Chapel, John Paul Stevens, AB'41, received the

Alumni Medal, the highest honor given by the University's alumni association.

Later that day he was also recognized with the Laboratory Schools' Distinguished

Alumnus Award. The two awards are fitting tributes, not only because Stevens-an

Associate Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court since 1975-has had a legal career

that is as distinguished as they come, but also because Stevens is a true son

of the University community. He grew up near the corner of 57th and Kenwood and

in many ways is an intellectual heir of the Lab Schools' founder, John Dewey.