Off-key

Smash

>> What

do Man of La Mancha, A Little Night Music, Ragtime, and Urinetown

have in common? All won Tonys for best musical score. The one with the most unlikely

title is - you guessed it - the one composed by Chicago grads.

Greg

Kotis, AB'88, and Mark Hollmann, AB'85, didn't worry much about their show's crowd-pleasing

potential when they wrote Urinetown The Musical. Instead, they wrote a

story in which the downtrodden do not triumph, the handsome hero is thrown from

a rooftop, and much of the action takes place outside a public toilet.

Mark

Hollmann (left) and Greg Kotis share a perch in the church where their show got

its start.

"What

you have to understand," says Kotis, "is that we didn't expect anyone

to see it. We had total freedom to write exactly what we wanted, because we fully

expected to be performing to audiences of two or three."

Hollmann

and Kotis-veterans of Chicago's improv and experimental theater scene-even poke

fun at their low expectations in the Urinetown script, when a wise waif

named Little Sally tells the cop-narrator Officer Lockstock: "I don't think

too many people are going to come see this musical."

Little

Sally's prediction proved wrong. Urinetown is a Broadway hit, often filling

the house at the Henry Miller Theatre a half block from Times Square. Audiences

of two or three? Make that millions watching excerpts of Urinetown televised

during the Tony Awards ceremony June 2 on PBS. On that night Kotis and Hollmann

shared the Tony for best score of a musical, Kotis received the Tony for best

book (that is, script), and director John Rando won the Tony for best direction

of a musical.

A

touring company will take Urinetown on the road next summer, starting in

San Francisco and visiting Los Angeles, Denver, Boston, and other cities not yet

confirmed. A production opened this summer in Seoul, South Korea, and others are

planned for London next spring and for Tokyo in summer 2004.

New

York Times critic Bruce Weber called the show "a sensational piece of

performance art, one that acknowledges theater tradition and pushes it forward

as well…. Simply the most gripping and galvanizing theater experience in

town.… And did I mention that Urinetown is hilarious?"

Kotis

conceived the heart of the story on a drizzly afternoon in Paris in 1995, when

the 29-year-old struggling actor found himself short of cash at the end of a solo

backpacking trip. That day, he was wandering near the Luxembourg Gardens, ruminating

about the story of Hemingway trapping pigeons in the park for food. "Off

in the distance, shrouded in the mist, I saw one of these pay toilets. I had been

thinking very seriously of going to the bathroom."

Then

again, Kotis thought, maybe he could hold off and save the 2 1/2 francs for dinner.

As he considered his choice, he got the idea for a musical in which private toilets

are banned, and rich and poor alike must pay to answer nature's call. Kotis "saw

the show in a flash. I knew it had to be a musical. I knew it had to be dark and

ridiculous and absurd." The title came in a similar flash.

For

a decade, Kotis had been turning story ideas into theater, first for the University's

comedy group Off Off Campus, while studying political science; next as a member

of Chicago's storefront improvisational group, Cardiff Giant Theater Company,

where he met Hollmann; and then as a founder of the Neo-Futurists-a collective

that creates interactive, "non-illusory theater"-where he met his wife,

Ayun Halliday, as well as Spencer Kayden, who plays Little Sally in Urinetown.

That

rainy afternoon in Paris, Kotis was weeks away from leaving Chicago to start a

New York branch of the Neo-Futurists company, and he immediately thought of Hollmann

as a collaborator. He'd teamed up with Hollmann before on six shows with the Cardiff

Giant ensemble, beginning when Kotis was a fourth-year and Hollmann was two years

out of college. Hollmann not only knew acting, having won the College's Louis

Sudler Prize in the arts at graduation, but he was also trained in composition

and orchestration. Watching musicals as a regular at Doc Films had emboldened

Hollmann to switch his major from political science to music, and he staged his

first musical, Kabooooom!, at Black Friars. After college, he played trombone

in a rock band Maestro Subgum and the Whole and piano for Second City's touring

company, and in 1993 he moved to New York to work as a composer, lyricist, and

word processor.

When

he and Kotis tackled the Urinetown project in earnest in 1997, they created

a drought-stricken city. To conserve water (and generate cash flow), an evil tycoon

aided by corrupt politicians controls "public amenities." It costs money

to pee, and it's even more costly not to pay. Anyone peeing en plein air

is "disappeared" to the mysterious Urinetown. Although the musical incorporates

stock plot elements (good vs. evil, star-crossed lovers), Kotis and Hollmann don't

allow the audience to lose itself in the fantasy: the characters repeatedly mention

that they're staging a show. When Little Sally suggests to Officer Lockstock that

a musical about a drought should touch on hydraulics, Lockstock replies, "Sometimes-in

a musical-it's better to focus on one big thing rather than a lot of little things.

The audience tends to be much happier that way. And it's easier to write."

The aim of this self-referential style, Kotis says, is to break down the wall

between audience and actors, to convey that "we know that you know that we

know that you know that this is a show."

Intense

and articulate, Kotis is both confident in his gifts and pessimistic about the

fate of the world. Hollmann's personality provides a counterpoint: he is calm

and understated, a craftsman with an old-fashioned willingness to believe in happy

endings. As they worked, the two played off each others' strengths; Hollmann's

affection for the conventions of musical theater served as a foil for Kotis's

mordant wit.

Hollmann

wrote a score that ranges from sweet to rousing to menacing, with allusions to

Kurt Weill's The Threepenny Opera and Marc Blitzstein's The Cradle Will

Rock. While Hollmann's music pays homage to the musical's potential to transport

its audience, Urinetown's lyrics and plot puncture those expectations.

For instance, in a scene between the doomed hero and his new love, Hollmann and

Kotis yoke a soaring melody with the lyrics: "Someday I'll meet someone whose

heart joins with mine/aortas and arteries all intertwined." The scene ends

as the hero offers a farewell salute with his toilet brush.

Working

together on the show Sunday afternoons in the Christ Lutheran Church in Manhattan,

where Hollmann was organist, the two men focused on constructing the musical,

not on how far it would go.

"Mark

and I come from a tradition in which you come up with a show and you do it,"

explains Kotis. "Doing it means getting your friends together and renting

a space, usually a black box, a storefront. You send out press releases, you try

to get listed, and you have a mailing party. Hopefully you don't lose too much

money. And you hope you get a review and that someone says something nice about

you, and you're one step closer to making a living in theater full time."

Kotis

and Hollmann were New Yorkers by then, but they created Urinetown with

a spirit owing more to the communal culture of Second City than to the ethos of

New York City-there, Kotis says "it's about talent making its way on its

own." Their years of improvisational theater played a role as they bounced

ideas off one another. "It really did draw on our experiences up on our feet

at Jimmy's Woodlawn Tap," says Hollmann.

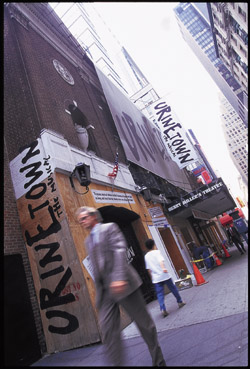

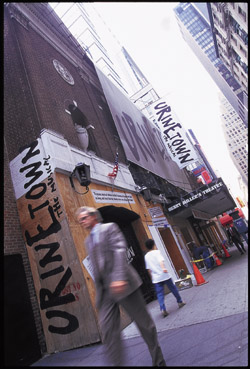

Even the signage for Urinetown sports an ad hoc air.

While

working their day jobs (Kotis as a location scout for TV and films, Hollmann still

processing words), they finished the show, and early in 1998 found singers to

record a demo in the church. Compensation was a copy of the tape. Because renting

a storefront costs too much in New York, Hollmann and Kotis sent inquiries to

more than 100 agents, theaters, and development organizations-enclosing the script,

or the tape, or a synopsis, sometimes just a pitch letter. No one bit.

Then

one summer day in 1998 Kotis described the show to John Clancy, artistic director

of the New York International Fringe Festival. Captive atop a ladder while painting

a theater lobby ceiling, Clancy heard out Kotis's spiel. What Kotis describes

as the team's "incredible luck" kicked in: Clancy liked the concept

and encouraged them to apply to the festival. The next spring, Hollmann and Kotis

found a cadre of good actors stuck in the city without summer stock jobs who agreed

to do 12 performances at the festival for a flat fee of $50 apiece. More good

luck ensued. A Canadian troupe slated to do the festival's centerpiece show was

blocked by immigration at the border and had to cancel. Then, of 150 shows at

the Fringe, Urinetown snagged the theater most convenient to the ticket

booth. The musical was the festival's sold-out hit.

The

biggest break came when the playwright David Auburn, AB'91, saw the show there.

Auburn, whom Kotis had auditioned for Off Off Campus a decade earlier-and who

in 2001 would win a Pulitzer Prize for his drama Proof-waited only until

intermission to phone a potential backer for Urinetown. By winter that

producer had joined with three other backers, but the show was delayed for a year

while they searched for a theater with the same grungy feel of the former auto

repair shop that had housed the show at the Fringe. In spring 2001 Urinetown

opened off Broadway in a former courtroom. By then the producers had found John

Rando to direct and landed musical-theater warhorse, Tony winner, and TV actor

John Cullum to play the pay-toilet magnate. During its two-month run the show

created buzz and drew crowds, justifying a move to Broadway. Opening night was

slated for September 13.

Their

luck seemed to have run out: after the World Trade Center attacks, New York was

not likely to embrace what Kotis calls "a doomsday musical." Hollmann

recalls, "It looked really bleak at that point, because we weren't a show

with a happy ending." But Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's insistence that New York

shows go on, and his handout of tickets to public safety workers and people grounded

after September 11, proved effective. Urinetown opened September 20. "It

was a wonderful thing to be a part of," says Kotis. "To feel like you

were being rescued by your fellow citizens and also offering them a place to come

together."

Kotis,

father of two, has quit his day job and is living on royalties. Hollmann still

works at word processing, 10-6 daily, but he has left his post as church organist

and feels established enough to marry artist Jilly Perlberger in October. He and

Kotis are working on their next musical, which takes place under water.

Success

is bittersweet for Hollmann. "We can never go back to a storefront. Part

of that is sad. I think of all the people we've known, we've struggled with. It's

amazing to me that we've had a different magnitude of experience than they have."

He frets that winning a Tony will "make people say 'yes' to me all the time,"

but he expects that his partnership with Kotis will provide the antidote. "We

still have each other to differ with." Kotis views the very fact of Urinetown's

Broadway production as a gift. "We won the lottery," he says.

There's

yet more proof in the script that the writers didn't expect success. Early in

the show, Officer Lockstock interrupts Little Sally's attempt to explain the plot

to the audience.

Officer

Lockstock: You're too young to understand it now, but nothing can kill a show

like too much exposition.

Llittle

Sally: How about bad subject matter? Or a bad title, even. That could kill a show

pretty good.

As

it turned out, the joke is on Kotis and Hollmann: Urinetown is alive and

well.

![]()