|

||

|

Peer Review ::

A novel idea

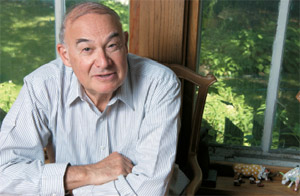

Professor Richard Stern recalls the visiting-writers program begun in the 1950s.

Fifty

years ago this spring, I opened a letter, in the tiny Quaker Hills, Connecticut,

post office, inviting me to interview at the University of Chicago. I borrowed

money for plane fare and a decent suit and flew to Midway Airport. On the

real Midway, I went from one professorial interview to the next, had lunch

with another inquisitorial group checking out my table manners, then was

driven around the city by the chair of the Committee on General Studies,

Norman Maclean, PhD’40. Left hand on the wheel, right hand pointing

to Frank Lloyd Wright houses, he told me how close in every way the University

was to the city—“Modern sociology was born here out of the closeness”—how

the 1909 Burnham Plan saved Chicago from the fate of Cleveland, Duluth,

Erie, and other lakeside cities, what the sturdiest urban tree was (the

locust), how the solitude of woods was half an hour from his office, and

how he wanted me to make students real writers of fiction, poetry, and—his

chief interest—BA and MA committee essays. I was to be the committee’s

first hired hand, the University’s first professional writer since

Thornton Wilder in the ’30s. “And Wilder only saw writers after

his literature classes.” I was also to be the committee’s secretary

and to teach courses in the novel and modern drama for the English department.

Fifty

years ago this spring, I opened a letter, in the tiny Quaker Hills, Connecticut,

post office, inviting me to interview at the University of Chicago. I borrowed

money for plane fare and a decent suit and flew to Midway Airport. On the

real Midway, I went from one professorial interview to the next, had lunch

with another inquisitorial group checking out my table manners, then was

driven around the city by the chair of the Committee on General Studies,

Norman Maclean, PhD’40. Left hand on the wheel, right hand pointing

to Frank Lloyd Wright houses, he told me how close in every way the University

was to the city—“Modern sociology was born here out of the closeness”—how

the 1909 Burnham Plan saved Chicago from the fate of Cleveland, Duluth,

Erie, and other lakeside cities, what the sturdiest urban tree was (the

locust), how the solitude of woods was half an hour from his office, and

how he wanted me to make students real writers of fiction, poetry, and—his

chief interest—BA and MA committee essays. I was to be the committee’s

first hired hand, the University’s first professional writer since

Thornton Wilder in the ’30s. “And Wilder only saw writers after

his literature classes.” I was also to be the committee’s secretary

and to teach courses in the novel and modern drama for the English department.

A pretty full plate, one which helped turn off the first man offered the job, Donald Justice, who happened to be my oldest friend. Just before the invitation letter came, I’d heard from him that both the University and the city scared him and his wife, and that although he enjoyed Maclean, he thought he was a kook. “He goes on and on about Custer.”

Kooks were my specialty—I’m a fiction writer—and I liked everyone I met, especially Maclean. I didn’t learn for 30 years that he wanted to be my kind of writer. The only manuscripts he showed me were a speech on 18th-century English poets and his somewhat laborious book on Custer’s transformation from indolent West Pointer to hero. He told me to treat his manuscript as I, rather notoriously, treated student papers, so I marked it up with queries, arrows, and exclamations of disgust. He thanked me, then, apparently, put it away forever. For years I berated myself for that.

Anyway, that spring day. Chicago looked beautiful. Hyde Park was in bloom, the lake glittered with sails among the water-purifying stations, and the skyline looked like a three-master taking off into the blue. I’d spent 1954–55 at a small women’s college in New London, and although I had good students and friends there, it felt like the sticks. Unlike the Justices, I’d been born and raised in a big city, New York. The countryside and its small towns were where you vacationed, not where you lived.

Chicago was clearly not New York. Its ethnic borders were distinct and counted politically; indeed, local politics were like Italy’s, more theatrical than civic; the institutions—political, academic, religious, cultural, and financial—were in close touch. “You can know anybody you want to around here,” said Maclean. The best known Chicago cop was a hearty naif who went around ticketing aldermen, the press’s comic contrast to standard policemen such as the one who’d just stopped my friend, Tom Higgins, who was celebrating his new camelhair overcoat by speeding on the Outer Drive. Without looking at the cop, Higgins handed over his wallet, to which a five-dollar bill had been clipped. A beefy mitt reached inside the car, its fingers rubbing the new coat. “You’re getting a little big for five, Higgins.” Chicago. I loved it.

As for the University, I’d read an old issue of Life that showed rows of professors in academic garb under the headline “Is the University of Chicago the World’s Greatest?” Back in Connecticut, my colleague Paul Fussell and I leafed through the catalog noticing whole courses devoted to single works, one on E. M. Forster’s Passage to India, another on Beethoven’s C Sharp Minor Quartet. At Connecticut College, we covered 600 years of English literature in a semester. “This,” said Fussell, “is what I call a university.” (I later learned that E. K. Brown’s class on A Passage to India only got through two-thirds of it.)

It took me a year to see that the Chicago literary scene wasn’t all that great. There was a hazy notion of a tradition of urban writers going back as far as Mrs. Kinzie, the author of Wau-bun; the names Hamlin Garland, Theodore Dreiser, James Farrell, and especially Nelson Algren were known, but largely the way stamp collectors know geography. When I gave a Channel 11 lecture on Chicago writers I think only Maclean enjoyed it. The lecture ended with The Adventures of Augie March, the greatest Chicago novel, whose author split his time between upstate New York and the University of Minnesota. I had talented students (in my first class were the poets George Starbuck, X’57, and David Ray, AB’52, AM’57), and there was a good campus literary magazine, the Chicago Review (soon to be involved in an obscenity trial focused on Burroughs’s Naked Lunch and Allen Ginsberg’s poems) but few colleagues seemed to know or care what was going on now in literature.

My second year, I asked Dean Napier Wilt for money to invite published

writers to talk to student writers. A burly, shrewd, Indiana romantic, Wilt,

AM’21, PhD’23, loved the idea of real writers roaming the campus

and dug up $2,000, enough to bring four of them in for a week each to discuss

their work, students’ work, and anything else. I invited Augie March’s

creator, Saul Bellow, X’39; my old Iowa teacher, Robert Lowell; Norman

Mailer; and John Berryman. They made a terrific splash, not only in the

English department, but also in the University community and the city. Adlai

Stevenson’s ex-wife, Ellen, gave parties for them at her Lake Shore

Drive brownstone—though when Berryman broke his leg there, she called

at 5 a.m. to say she had his bar bills so there’d better be no attempt

to sue her; there were interviews in newspapers and on radio; people from

all over town read the visitors’ books and came to their public lectures.

The next year I invited Flannery O’Connor (whose blue eyes glared

with bitterness when I picked her up at 3 a.m. at the Greyhound Station

after her plane had been iced down in Louisville), Ralph Ellison, Howard

Nemerov, and Kingsley Amis. Young writers started coming out of the woodwork

of urban silence. (A South Side postal clerk trundled his handwritten novel

over to Ellison.) Even Algren, who for years had Chicago’s literary

attention to himself, came around, and though he often got physically ill

around writer peers and betters, he seemed to enjoy what was going on.

When the decanal $2,000 no longer sufficed for four writers, the number went down to three, then two, and finally one. Still, the University and the city had gotten into the habit of seeing, hearing, and reading the best active American writers. The bookstores stocked and sold their books, and young writers were ignited. Former students, writers and non-writers, have written me for decades about their delight in these visitors. It was, I think, not only the excitement of having fine new books talked about by those who’d written them, but also the contact with personalities whose lives often involved at least the imaginative transgression of social and psychological borders.

Now authors don’t have to be seduced by University dollars to come to Chicago. Part of their writing life is the promotional trip, planned by publishers and coordinated with such bookstores as 57th Street Books, radio and television programs, and whatever groups sponsor their readings. If anything, there’s a glut of appearances, and although there are surely plenty of times when the mental flame passes from writer to audience, I’m not sure that there is anything like the concentrated creative excitement of those early visits.

Almonds to Zhoof: The Collected Stories of Richard Stern will be published

this month by Triquarterly Books (Northwestern), which has reissued three

of his novels: Stitch, with a foreword by Ingrid Rowland; Other Men’s

Daughters, foreword by Wendy Doniger; and Natural Shocks, foreword

by James Schiffer, AM’74, PhD’80. Stern, the Helen A. Regenstein

professor emeritus of English and American Language and Literature, has

won prizes for his stories and novels, as well as for his memoir, A

Sistermony.