|

||

|

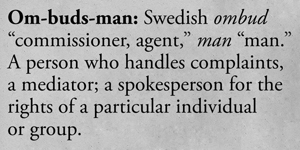

Complaint agents

It is an office of the students, by the students, and for the students. Student staffed and answering only to the University president, the ombudsperson’s office, “cutting red tape since 1968,” as its motto goes, bills itself as the first of its kind in the country. The ombudsperson and associate ombudsperson investigate complaints on a case-by-case basis and recommend institutional changes.

For

Heather (not her real name), AB’05, the trouble began last spring,

her final quarter. Her long-dormant asthma flared up and she missed classes,

soon facing the possibility of not graduating on time. When the asthma first

kicked in, Heather tried self-medication, pulling out her old nebulizer

and steroid inhaler, but to no avail. Around fourth week, two professors

informed her that her absences were endangering her grade. She explained

she was ill, and one professor wanted documentation while the other “just

wanted me to come to class.”

For

Heather (not her real name), AB’05, the trouble began last spring,

her final quarter. Her long-dormant asthma flared up and she missed classes,

soon facing the possibility of not graduating on time. When the asthma first

kicked in, Heather tried self-medication, pulling out her old nebulizer

and steroid inhaler, but to no avail. Around fourth week, two professors

informed her that her absences were endangering her grade. She explained

she was ill, and one professor wanted documentation while the other “just

wanted me to come to class.”

She went to the Student Care Center, which didn’t provide a note

but did give her allergy medicine. When her symptoms persisted, she was

prescribed a slow-acting, daily asthma medication. Around eighth week she

relapsed, this time combating both asthma and the flu.

Although her assignments were late and she missed classes, Heather expected

only a grade deduction—she was still earning As and Bs. So it came

as a shock when, on Wednesday of ninth week, her Spanish professor said

she was “no longer welcome” in the classroom. That Friday, her

academic adviser said there was no way she could graduate in June. “I

just sat there and cried for an hour straight,” she says.

Heather’s boss at Uncle Joe’s Coffeeshop recommended that she

see Phil Venticinque, AB’01, AM’02, last year’s ombudsperson

and a classics graduate student. She made the appointment with less than

a week to “figure everything out”—senior grades were due

Friday of tenth week.

The following Thursday, Heather’s adviser had good news. Venticinque

had spoken to the Romance Languages & Literature department, which had

agreed to let her take a language placement test, usually reserved for entering

students. If she tested out of Spanish 103, she would receive credit for

the class, though her transcript would report a W, for withdrawal. The next

morning she learned that the Spanish competency test she’d taken earlier

that week would give her credit, and, at last, “everything fell into

place.” Though her convocation card was handwritten, Heather says

with a laugh, “I got to graduate and I got to walk, and it all worked

out in the end.”

Perhaps former University president Edward Levi, PhB’32, JD’35, envisioned such happy endings when he launched the office in 1968. Levi, then provost, founded the position in response to students’ complaints that no one was listening to them, according to deputy dean of students Roberta Cohen, who oversees the ombudsperson application process.

“The purpose is not to have the student win or lose, or the University win or lose,” says Victor Muñiz-Fraticelli, AM’03, the 2005–06 ombudsperson and a fifth-year political-science graduate student. “It’s to bring the student back to the University. The process of reconciliation,” he emphasizes, “is the driving spirit behind the office itself.” A University of Puerto Rico law school graduate who left law because the courts are “not the kind of atmosphere I thrive in,” Muñiz-Fraticelli puts his legal skills—problem solving, mediation, dispute resolution—to use in his current position.

Landing the job takes three rounds of interviews. Nine to 15 people, Cohen estimates, usually send in cover letters, résumés, and two recommendations. First the applicants interview with two administrators, who quiz them on hypothetical scenarios. In the second round, two to four candidates go before a student-faculty committee, which recommends one or two people to the president. He interviews them and makes the final choice. Once appointed, the ombudsperson and associate start their jobs, Muñiz-Fraticelli says, without “any training beyond our experience as students.”

On the job, “I’ve learned that there’s some things that have no acceptable solutions,” says Muñiz-Fraticelli, who served as associate last year. “We’re often forced to be very imaginative to help the student in some way, even if it’s not the student’s preferred outcome.” Although he finds these cases difficult, “it’s the heart of the job.”

Typically, the ombudsperson works 15 hours a week, while the associate—currently fourth-year Law, Letters, and Society major Kirk Schmink—works ten. Muñiz-Fraticelli holds ombudsperson and TA office hours simultaneously, a common practice because the “vast majority” of students make appointments via e-mail. Those appointments seem to be on the rise. The office handled 79 cases last year, 52 the year before, and 73 in 2002–03. Recent complaints ranged from plagiarism to housing contracts to financial aid.

Muñiz-Fraticelli and Venticinque emphasize the importance of students staffing the office. “Students have a tendency to identify with us,” Venticinque said. “Often students will come to us before they go to their advisers.” Yet many administrators who support students, including academic advisers and assistant resident heads, often forget to contact the ombudsperson. “I haven’t talked to the ombudsman in years,” admits Associate Dean of Students in the College Lewis Fortner. “I don’t even know who the current ombudsman is.”

Because many students remain unaware of the office’s existence, Muñiz-Fraticelli plans to publicize it. “The most important thing for the office right now is exposure,” he says. “We want students to know the office is here, and we want them to tell their friends.”