|

||

|

Citations

Paging God to the ER

Though their work is steeped in science, American physicians are nearly as religious as their patients. According to a study by Chicago medical instructor Farr Curlin, 76 percent of physicians believe in God—compared with 83 percent of the US population. Fifty-nine percent believe in some kind of afterlife, and 90 percent attend religious services at least occasionally. Curlin’s study, published in the July Journal of General Internal Medicine, also found that U.S. doctors are 26 times more likely to be Hindu, seven times more likely to be Jewish, six times more likely to be Buddhist, and five times more likely to be Muslim than the U.S. population. While family practitioners and pediatricians were most likely to look to God for guidance, psychiatrists and radiologists did so the least.

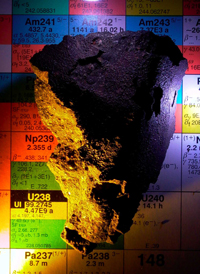

Meteorites, like this Australian one, helped determine the galaxy’s

age.

Reset the cosmic clock

Finally, the Milky Way is showing its age. After decades of unverified guesstimates about the galaxy’s birth date, University geophysicist Nicholas Dauphas has taken a more grounded approach. Combining telescopic data on the chemical makeup of distant halo stars with similar measurements taken from meteorites, Dauphas calculated the decay of two radioactive elements, uranium-238 and thorium-232, and counted backward to the Milky Way’s origin—which, he reported in the June 29 Nature, was 14.5 billion years ago, give or take a couple billion. That figure essentially supports scientists’ earlier supposition that the galaxy formed 12.2 billion years ago, but with far weightier evidence.

Like molasses in January

A years-old window pane has a thicker bottom than top because the atoms in glass flow, ever so slowly, downward. Scientists have wondered if atoms arrange themselves differently in glass than they do in liquids. Physics professors Heinrich Jaeger and Sidney Nagel and physics graduate student Eric Corwin studied the flow of tiny glass beads under various pressures to learn how materials switch from “jammed,” or solid, behavior to flowing behavior. Using a shear cell, similar to a motorized pepper grinder, the scientists ground the beads together and charted at which pressure they began to flow. The findings, published in the June 23 Nature, may have important applications—from ensuring that granular structures like dams, levees, and railroad supports stay rigid to helping farmers release a flow of grain from their silo.

Breathing lessons

Tiny doses of nitric oxide (NO) reduce blindness, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, and other problems facing premature newborns with underdeveloped lungs. U of C pediatrics professor Michael Schreiber led a study, published in the July 7 New England Journal of Medicine, that followed 138 babies—70 from the control group and 68 from the nitric-oxide group. At age two, 24 percent of infants who received NO had delayed mental development or a disability, versus 46 percent of those who received a standard oxygen treatment. Nitric oxide, not to be confused with nitrous oxide or “laughing gas,” occurs naturally in the body and helps the lungs absorb oxygen by relaxing the lung’s blood vessels.

When bacteria attack

University scientists have shed new light on the attack mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium that lives in moist places, including the intestines of about three percent of healthy people. Surgery professor John Alverdy and colleagues found that Pseudomonas knows when the host is most vulnerable via intercepted signals from interferon-gamma, a chemical messenger used by the immune system to drive out the bacteria—and attacks before the host can recover his or her strength. The study was published in the July 29 Science.