|

||

|

Peer Review ::

Paper route

East meets West in Claud Gurney’s luxury wallpaper.

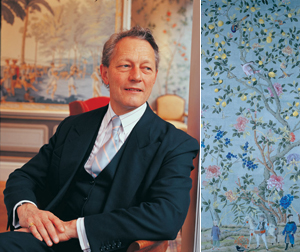

Claud Gurney and his firm’s Abbotsford wallpaper design.

The hottest design craze in 18th-century Europe was chinoiserie. Trendsetters couldn’t get enough of “the Chinese taste” for their magnificent homes and gardens. From St. Petersburg to the English countryside, and even across the Atlantic (founding father George Mason had a Chinese room designed for his Gunston Hall in Virginia), porcelain vases and Chippendale’s Chinese furniture were must-haves. And then there was handpainted, made-to-order wallpaper, depicting tree-branch lattices graced by exotic songbirds and masses of peonies and rhododendrons seldom seen by Europeans. These colorful, vibrant papers were made in China—and difficult to come by.

The merchant entrepreneurs of the East India Company risked their fortunes and sometimes their lives sending out ships to bring back the papers and porcelains that bore intriguing images of faraway lands—journeys that, even when successful, could take several years. Travel time to China simply to place an order could take five months to a year. “Sometimes a client would order the paper, then die,” says Claud Gurney, AM’83, only half joking about the time the endeavor took. “And a grandchild would end up getting it.” Today it’s far easier to own Chinese papers, fabrics, and porcelain. But for Gurney, 56, whose specialist wallpaper company de Gournay is headquartered in Kent, England, securing such products is still an adventure.

That adventure began shortly after Gurney, who had been a CPA consultant for Coopers & Lybrand in Paris when he decided to study economics at Chicago, earned his master’s degree and returned to consulting. While conferring with a New York design company about a Chinese room for his London home (growing up in Surrey, Gurney had been introduced to Chinese wallpaper at his aunt’s house), the creative bug bit. De Gournay—the company uses the original French version of his family name—was born. When asked, “Why wallpaper?” Gurney responds with a grin, “Well, I always knew I had good taste.”

So in 1984 he went to China to scout out possibilities. “There were some factories doing bird paintings, but many of the old hand-painting skills were lost,” Gurney says. He partnered with the Chinese government to produce the wallpaper but found the Chinese officials more keen on mass production than creating the luxury product he envisioned. Gurney ended the joint venture and founded his own company, eventually opening a factory in Wuxi, near Shanghai.

Today de Gournay features 25 Chinese patterns and a dozen 19th-century French panoramic designs. Each paper is hand-painted by some of the firm’s 180 China-based artists. Nearly all patterns can be customized—scale and color schemes altered, design elements added or removed. For example, notes Margot Tushingham, de Gournay’s head of retail sales, Earlham—an array of tree peonies, birds, and butterflies—is the company’s most popular seller, but because production is done to a buyer’s specifications, every installation can look and feel like a new paper. Each nine-foot-tall panel starts at more than $600, and a completely papered room averages $12,000. Once a customer approves a design sample, delivery takes eight to ten weeks.

De Gournay boasts an impressive clientele: English fashion designers Lulu Guinness and Matthew Williamson as well as the conservation organization English Heritage (de Gournay papers were commissioned for the organization’s restoration of Twickenham’s historic Marble Hill House). The walls of Geneva’s Four Seasons and Las Vegas’s Bellagio wear de Gournay, as does the jewelry department at New York’s Bergdorf Goodman. And at the 2004 G8 summit in Sea Island, Georgia, dignitaries dined in a room papered by the firm.

One of de Gournay’s most striking designs is Abbotsford, based on the Chinese drawing room at Sir Walter Scott’s 19th-century home in Melrose, Scotland. Abbotsford is one of three “historic sets” the company produces on India tea paper. Although Chinese wallpapers were originally made from tiny pieces and then pasted together to form long panels, today most panels are made in a single large sheet. In the India tea-paper technique, which recreates the 18th-century method as faithfully as possible, small pieces of paper are affixed to four-by-ten-foot panels. Artists then distress the panels to replicate the look of sundried wallpaper before painting the design.

In addition to wallpaper, de Gournay produces porcelain figurines, armorial dinner services, and hand-painted fabrics—from large draperies to silk shawls. Though best known for its historic reproductions, the firm now creates more modern designs by paring down original patterns for a sleeker look. Los Angeles interior designer Kelly Wearstler and British couturier Matthew Williamson have commissioned patterns using nontraditional colors and textures, such as metallic surfaces. “Some people know what they want when they come to us,” says Gurney, “and others haven’t a clue.” For inspiration, de Gournay’s creative team—headed by a Florence-based director and eight designers in London and China—maintains an archive of tens of thousands of designs.

With showrooms in London, Melbourne, New York, Moscow, and Florence, de Gournay is still expanding its reach. The company recently established a showroom in Istanbul, and China, whose growing economy has spurred interest in luxury goods, may be next. Finally, a potential factory in Poland may bring the work closer to home. While the journey across the continents is hardly as long or as treacherous as it used to be, Gurney notes, “China is still a long way away.”