|

||

|

:: By Brooke E. O’Neill, AM’04

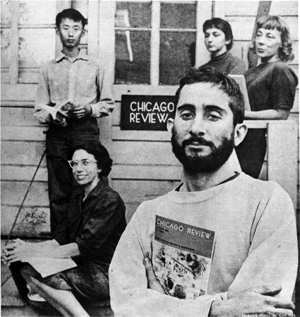

:: Photo from Chicago Tribune, November 9, 1958. Photograph by Carl Turk. Courtesy Regenstein Library.

60-year Review

By the time the Massachusetts Supreme Court reversed a Boston ban on William Burroughs’s heroin-addled, sexually charged satire Naked Lunch in 1966, the Chicago Review should have been dead. Eight years earlier—upon the suggestion of Allen Ginsberg, whose work had appeared in the campus literary quarterly—editor Irving Rosenthal published two excerpts from Burroughs’s book. The third installment, slated for the Winter 1959 issue, had just gone to press when the late Chicago Daily News columnist Jack Mabley blasted the University’s laissez-faire relationship with the student publication. “Filthy Writing on the Midway,” declared the front-page headline.

Rosenthal (front) holds the controversial Naked Lunch issue.

The entire staff resigned except Pak (back left).

Chancellor Lawrence Kimpton soon tightened the reins, ordering Rosenthal to remove any potentially scandalous pieces from the forthcoming edition. Rosenthal—who along with poetry editor Paul Carroll, AM’52, would later publish the suppressed material in a new magazine called Big Table—pulled the entire issue. Three days later he and all but one of the editors, Hyung Woong Pak, resigned. Under the administration’s wary eye, Pak switched the focus from the beats to European literati, publishing a special issue on “Existentialism and Literature” that summer—and keeping the publication afloat.

Now in its 60th year, Chicago Review has given voice to philosophers, poets, and fiction writers including Susan Sontag, AB’51—her first published work, a review of H. J. Kaplan’s novel The Plenipotentiaries appeared in the Winter 1951 issue—former poet laureate Robert Pinsky, and novelist Joyce Carol Oates. Despite the Burroughs brouhaha, financial hiccups, and what former poetry editor Devin Johnston, AM’94, PhD’99, calls “pockets of incoherence” created by an ever-revolving staff, it has become one of the oldest and most innovative literary quarterlies in the country.

Tucked in the third floor of the Lillie House at 5801 South Kenwood Avenue, today’s Review enjoys an easy coexistence with the University. “We thrive in a culture of benign neglect,” says editor Joshua Kotin, a fourth-year English doctoral student. Unlike comparable magazines such as the Kenyon Review and Yale Review, both of which are faculty-edited, the graduate-student staff controls all editorial content. Aside from an annual $5,000 stipend from the Humanities Division, all income is generated directly by magazine and ad sales.

Hailed for its poetry and special issues (recent topics included Polish writing and British poet Christopher Middleton), the magazine blends fiction, poetry, book reviews, author interviews, and archival materials. Humanities dean Danielle Allen calls it “one of the smartest literary productions out there.” Think edgier than the New Yorker and “academic without being Critical Inquiry,” says 2000–05 editor Eirik Steinhoff, AM’99, now working on his dissertation on 16th- and 17th-century English poetry. Frequent editorial turnover, the side effect of a student staff, ensures no one school of thought or aesthetic dominates. Authors, says Steinhoff, must pay “reflexive attention to language,” giving people “something to chew on.”

For the quarterly’s 60th birthday, editors have given readers plenty of sustenance. In September they planned to launch a “satellite” retrospective on the publication’s Web site featuring pieces from its first five decades. First compiled by early-1990s editor David Nicholls, AM’89, PhD’95, for an out-of-print 50th anniversary issue, excerpts include early short stories by Philip Roth, AM’55, and Raymond Carver, poetry by Tennessee Williams and Jack Kerouac, an attack on American literature by Henry Miller, and the first chapter of Naked Lunch.

For many staffers, compensated with little more than Medici pizza—head editors earn roughly $1 an hour when the journal can afford it—a stint at the quarterly leads to a lifelong passion for publishing. As Steinhoff half-jokes, “A dissertation, at best, has an audience of three and takes years. Chicago Review is produced in an edition of 2,000 and then gets sent out to the world. That’s a hard thing to stop trying to satisfy.” An overview of past editors supports his point: Nicholls directs book publication at the Modern Language Association. Johnston, an editor from 1995 to 2000 and a poet in his own right, heads Flood Editions, a short-fiction and poetry press. Keith Tuma, AM’80, PhD’87, an English professor at Miami University of Ohio and editor in the ’80s, has edited Rainbow Darkness: An Anthology of African American Poetry (Miami University Press Poetry Series, 2006) and Anthology of Twentieth-Century British and Irish Poetry (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Current editor Kotin admits the ongoing search for new talent—and subscribers—tends to pull him away from his dissertation. A recent promotion offered a free Flood Editions poetry book in exchange for a two-year renewal. (“They go like hotcakes around Christmas,” says Steinhoff.) Libraries—which comprise more than half the magazine’s subscriber base—continue to move from hard-copy to digital resources, giving Chicago Review more subscription worries. The editors try to draw readers by cultivating up-and-coming artists such as poets Jacqueline Waters and Peter O’Leary, AB’90, AM’94, PhD’99. Such talent, says Steinhoff, places the Review “in the conversation that we want it to be in and bring[s] new participants to that conversation.”

It’s a dialogue readers have come to expect—and, if novelist Henry Miller was correct, may have a hard time finding elsewhere. “It is as if all the books, all the magazines, everything printable (including the dictionaries and encyclopedias) were written by the same standardized mind, written by some incredible monster of unilateral taste and sclerotic imagination,” he ranted in the Fall 1955 issue. Years later Chicago Review editors continue to try to prove him wrong, embracing nonstandard writing and innovative thought.