|

||

|

Peer Review ::

Tut treasure trove

For museum-goers, David Silverman brings Egypt’s boy king to life.

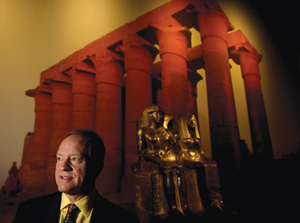

David Silverman stands before granite statues depicting Tut’s probable

great-grandfather, Thutmosis IV (reign 1400–1390 BC), and great-great-grandmother,

Tiya.

David Silverman’s favorite object in Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs isn’t made of gold, like so many iconic Egyptian artifacts. His preferred item—whose image graces the cover of his book Masterpieces of Tutankhamun (Abbeville Press, 1978) and whose inclusion is “one of the reasons I was so excited” to be the exhibit’s national curator in the United States—is a wooden, armless, torso-and-head likeness of the boy king. Slightly smaller than life-size, the statue’s forehead bears a cobra, a symbol of royalty, and the face is painted a rich sienna. British archaeologist Howard Carter, who discovered Tut’s tomb in 1922, suggested the torso might be a mannequin to hold the king’s robes and jewelry. Yet Silverman, PhD’75, isn’t so sure. “There are statues without arms used for religious rituals. I have a feeling that’s what this was used for.” He admires its lifelike appearance. “The eyes don’t follow you,” and they seem “to be looking beyond this world,” he says. “It’s a showstopper.”

The torso wasn’t part of the first U.S. King Tut exhibit—but Silverman was. In 1977, as a doctoral student and assistant research curator at the Oriental Institute, he became project Egyptologist for the OI–Field Museum’s leg of Tut’s first American tour. This time around Silverman, a University of Pennsylvania professor and curator of the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s Egyptian section, is responsible for all exhibit text for the show’s two-year, four-city U.S. journey.

In Chicago during May preparation at the Field Museum—the third stop after museums in Los Angeles and Fort Lauderdale—Silverman, in jeans and a striped button-down shirt, follows a plastic-sheeting path through the museum’s first-floor construction zone. Small trucks carrying exhibit cases beep in slow reverse. Men high on ladders install spotlights. The workers are sculpting the space into 11 galleries highlighting the 9- or 10-year-old boy who, around 1332 BC, became the Egyptian Empire’s commander in chief, head of state, and high priest of every god.

Unlike the 1970s exhibit, when the Egyptian government and the Metropolitan Museum of Art chose 55 objects spanning Tut’s life, this display is bigger and broader. The government and Cairo’s Egyptian Museum sent 130 artifacts, 50 from Tut’s tomb and the remainder from the 15th century BC, when his ancestors built the empire. In the 1977 exhibit “we couldn’t talk much about this time,” Silverman says. “Now we have those objects” and can give context to Tut’s life.

The exhibit explains, for instance, the polytheistic religion that dominated Egypt in the 15th century BC. When Akhenaten, Tut’s likely father (and Nefertiti’s husband), ruled from around 1353 to 1336 BC, he began a religious revolution, changing the traditional capital cities from Memphis and Thebes to one at modern-day Amarna and forgoing all other gods in favor of one—Aten, the embodiment of the sun. Akhenaten changed Egyptian art and architecture, building temples to Aten that opened to the sky. “The people weren’t happy” with Akhenaten and his changes, Silverman says. “The people outside the new capital never saw him.”

Although there were two other rulers in the next three years before Tut assumed the throne, in his decade-long reign the boy king restored Egypt’s traditional religion, capitals, and architecture. One section of the exhibit includes items reflecting Tut’s daily life—objects placed in his tomb for use in the next world: four games (he was about 19 when he died), a duck-shaped ivory container for cosmetics, a decorative furniture chest, a lotus blossom cup, and multiple golden objects.

Silverman’s awe for these artifacts, especially the wooden torso, betrays his early fascination with their origin. Growing up in New Jersey, 15 minutes outside New York City, “I was dragged by my aunt and mother—who liked Egypt—to the Met,” Silverman says. “Kids either go for dinosaurs or Egypt. Often Egypt wins out. In my case it certainly did.” Earning a bachelor’s in art at Rutgers in 1966, he then came to Chicago and studied Egyptian language. “Learning hieroglyphics was love at first sight.” After finishing his PhD, he spent two years with the first Tut exhibit, joining Penn’s faculty in 1977. One of his doctoral students was Zahi Hawass http://guardians.net/hawass/, now Egypt’s secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. Hawass suggested Silverman curate the current U.S. exhibit, organized by Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society.

Before the objects arrived in Los Angeles for their first U.S. stop in June 2005, Silverman traveled to Switzerland to see them firsthand at Basel’s Museum of Ancient Art. There, he says, the items were displayed “more as an art exhibit.” A six-foot stone head of Akhenaten, for example, sat close to eye level. “Originally this was a 15-foot colossal statue,” Silverman explains. “The expression changes. If you put him up high you get the power, the uniqueness, the intensity of this individual.”

Although the four U.S. exhibits are configured differently based on each museum’s available space—the last stop is the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, where Silverman also will curate a companion display at the Penn museum—he has worked with designers to tell a historical account in each installation. The Field’s presentation, up through January 1, 2007, begins in a dark room as actor Omar Sharif narrates a two-minute introductory film (Sharif also voices the audio tour). Visitors then proceed through galleries about Ancient Egyptian daily life before Tut’s reign, the traditional religion, and Akhenaten’s religious revolution—in this section the colossal head looks down from above. They learn about the Egyptian concept of the afterlife and see photographs of Carter’s tomb discovery. They find out about Tut’s life and reign—one gallery is lined with a colonnade from a temple he built in Luxor—before reaching his tomb.

In the center of this small, dark chamber sits a virtual sarcophagus. A projector from above casts images of the three inner coffin layers, inside which lies the mummy. Display cases hold the golden items found with Tut’s body: a dagger and sheath, a falcon-shaped collar, an elaborate crown, a collar that was draped across his thighs, and an inlaid cobra sewn to his beaded headcap. Finally visitors see the results of medical studies to determine what killed Tut. Although X-rays taken in 1968 discovered damage to his anterior skull, Silverman notes, CT scans taken in 2005 offered proof that the head wound “didn’t cause his death.” Infection from an unhealed leg fracture, one research team believes, may have done him in.

Yet first, before anyone walks through the exhibit, the plastic walkways and construction equipment must disappear. On May 24 the production opens. Silverman begins his day at 5 a.m., appearing on ABC, CBS, NBC, WGN, and three radio stations before joining the 9 a.m. opening ceremonies. After the speeches he positions himself in the early sections while the first visitors cram each gallery. As guests approach him with questions, he answers with the enthusiasm of an Egypt-loving child at the Met.