|

||

|

College Report

By any name, uncommon

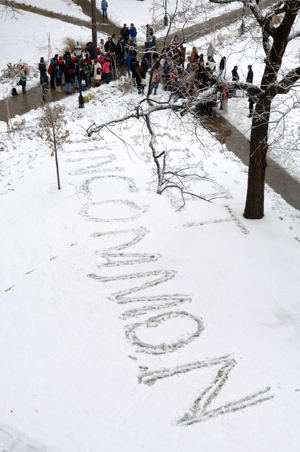

Mother Nature provided the canvas for the protesters’ “Keep

it UnCommon” message on the quads.

With Chicago’s first snowfall December 1 came plows, hats, rock salt, and protesters. On the main quads 50 students gathered, toting homemade signs that read, “I am not common. I like mustard” and “Your mother is common.” They chanted: “Who are we?” “Not Harvard!” “Who are we?” “Not Brown!” “Who are we?” “Chicago!”

The display of school pride-—as one sign put it, “UChicago is a nerd haven”—came in response to news that the College is moving away from its distinctive UnCommon Application. While retaining its quirky essay questions as a required supplement, the University plans to accept basic information (names, schools, scores) submitted through the Common Application. Established in 1975, the Common Application has grown from a pilot program of 15 universities to nearly 300 member institutions, including Harvard, Brown, Northwestern, and a dozen public schools. When the change takes effect, either in 2008–09 or the following academic year, the Admissions Office will continue to make Chicago’s own form available and to use the term UnCommon in some way.

Administrators hope the move will encourage more students, and particularly more diverse students, to consider the U of C. “Colleges using the Common Application claim that it helps them increase diversity,” said Vice President and Dean of College Enrollment Michael Behnke. “For instance, we know that the percentage of African American students using the Common Application exceeds the percentage of these students applying to the University.” According to Behnke, some 175,000 students used the Common Application in 2005–06, and nearly 300,000 are expected to file the form in 2006–07.

For the demonstrators gathered in the snow, increasing the number of applicants has drawbacks. Luis Lara, ’08, one of the protest organizers, fears Chicago’s uniqueness will be lost in the change. “We will just become a name in a list of about 300,” he said. “Our name won’t match up with anything about the school.” Furthermore, he argued, “the UnCommon Application has established itself as a very important tool and indicator of our University’s values. It has become the reason many students apply here.” For Lara, the UnCommon Application, as a complete package, represents what makes the University special. “It bothers me when students say that it’s OK to switch because we are keeping the essays. It’s not OK. We need to keep the entire application because of its symbolism and value.”

He voiced similar sentiments in an online petition he created, which 1,000 students and alumni had signed by December 6. “I wasn’t planning on applying to UChicago, but when I got the Uncommon Application in the mail, I couldn’t resist,” wrote Sangzi Chen, ’08. “The UnCommon Application defines the damned school.”

In a December 4 post to Chicago’s UnCommon Application blog, Dean of Admissions Ted O’Neill, AM’70, announced the change. “Even as we loved” the UnCommon Application “and patted ourselves on the back for being different and clever,” he explained, “we always feared that the students who might turn away from the UnCommon might be, disproportionately,” those “least comfortable with competitive college admissions,” including first-generation and low-income applicants. After most universities followed Harvard’s 1994 decision to accept the Common form, “we find that we are almost alone,” he said, “in requiring a separate and different application.” Applicants may still choose to use the UnCommon, and those who use the Common “will have to answer our interesting questions.”

Yet several of the 70 early responders to O’Neill’s post weren’t convinced. History major Deanna Day, AB’06, wrote that for her, a “first-generation applicant from a rural school,” Chicago was nevertheless an option. “Frankly, removing the UnCommon Application is insulting to those whom you’re trying to recruit. It sends a message to them that because their parents never went to college, the administration thinks that they’re incapable of filling out an extra form, or even of getting the joke.” Rather than changing the application process, she suggested, Chicago officials should advertise the school through more mailings and school visits.

While the partial change has its critics, supporters also have spoken up. Potential applicant Becca Maurer wrote on the Admissions blog, “I’m looking forward to the greater diversity in thought, background, and opinion that this could potentially bring to a school that originally caught my attention because of its uniqueness.” In a November 14 editorial, the Maroon too wrote in favor of the change, citing the Common Application’s accessibility and its potential to “lighten the load on all high school seniors” and to “help the U of C further improve its college ranking.”

Perhaps what all this discussion represents, whether in the Maroon, online, or on the quads, is the uncommon nature of Chicago students. Protester Daniel Aguilar, ’07, noted that the quads gathering “says something about what U of C students are like, where they place their priorities, and what they want out of college.” Chicago students care about their school’s character, and they aren’t about to let the issue rest without debate.