|

||

|

Original Source

Idea of Order

In 1915, when Wallace Stevens submitted “Sunday Morning” to Harriet Monroe at Poetry magazine, he was not a canonized, anthologized, or even recognized poet. He was a 35-year-old New York insurance lawyer, and his only major publication had been in Poetry’s pages a few months earlier, verses he’d entered in a war-poem competition. Monroe cut “Sunday Morning” nearly in half, reordered the five remaining stanzas, and ran the result in Poetry’s November 1915 issue. Its famous closing line, “Downward to darkness, on extended wings,” was in the middle.

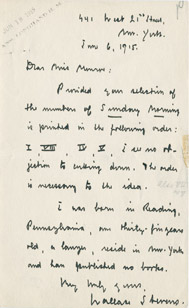

“The idea of mutilating this poem and taking out stanzas makes us uncomfortable,” says Liesl Olson, a Humanities Division assistant professor and Stevens scholar. “But he was completely unknown.” In letters to Monroe, Stevens negotiated gingerly, and mostly without success, to keep the poem’s structure intact. In the letter, at right, he wrote, “Provided your selection of the number of ‘Sunday Morning’ is printed in the following order, I, VIII, IV, V”—it wasn’t—“I see no objection to cutting down.”

“The idea of mutilating this poem and taking out stanzas makes us uncomfortable,” says Liesl Olson, a Humanities Division assistant professor and Stevens scholar. “But he was completely unknown.” In letters to Monroe, Stevens negotiated gingerly, and mostly without success, to keep the poem’s structure intact. In the letter, at right, he wrote, “Provided your selection of the number of ‘Sunday Morning’ is printed in the following order, I, VIII, IV, V”—it wasn’t—“I see no objection to cutting down.”

Owned by the University, much of Stevens’s correspondence with Monroe, along with typescripts showing her edits, are housed at the Reg’s Special Collections Research Center. Seeing firsthand how Monroe toyed with “Sunday Morning,” Olson says, prompts a clearer understanding of the poem. “You can see how it was constructed.”

Student discussions, she says, invariably confront whether to end the poem, as Stevens did, with the solitary image that opens it—a woman who should be in church, daydreaming in her peignoir over coffee and oranges—or with the naked, chanting “ring of men” Monroe favored. “He’s saying we can’t return to pagan times, that we’ve lost our religion and we are alone,” Olson says. “Stevens sees something very chilly about our secular paradise.” Monroe, meanwhile, was “going for a more uplifting poem.” In the end, Stevens won out: his 1923 book Harmonium restored “Sunday Morning” to its original configuration.