|

||

|

Peer Review ::

Paris match

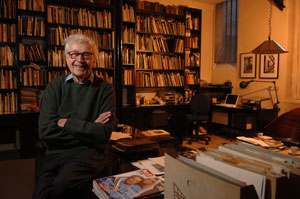

Photo editor John Morris finds a home for a lifetime of words and images.

The large, high-ceilinged office, lined with bookshelves and file cabinets, looked comfortably crowded. But six weeks earlier it had been standing-room only. On December 7, 2006—which happened to be his 90th birthday—John G. Morris, AB’37, watched as movers arrived at the Paris flat where he has lived since 1983 and drove off with 72 cartons of correspondence, periodicals, photographs, and other documents—all headed for Regenstein Library. Two days later the space filled again, this time with 200 guests for a post-birthday fete.

From Paris to the Reg: a photo editor’s archive.

In 50 years as a picture editor at Life, Ladies’ Home Journal, the Washington Post, and the New York Times, Morris assigned and chose many of the photographs that became part of the national psyche, from D-Day to Vietnam. Along the way he collected letters, tear sheets, photographic negatives and prints, and printed materials that formed the basis for his memoir, Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism (Random House, 1998). Now those materials will provide what Alice Schreyer, director of Special Collections Research at the Regenstein, calls a valuable resource: “Collections such as this one are essential to preserve the record of 20th-century visual culture.”

The John Morris Papers not only document his work with such giants of 20th-century photography as Robert Capa, W. Eugene Smith, and Henri Cartier-Bresson, but they also include a lot of personal history, including his years working for the Chicago Maroon. “I’ve been a saver,” admits Morris, who as a child collected postage stamps. “But I’ve also moved around a lot, and in the process some things have gotten lost.” Items that he didn’t lose include “the first essay I ever wrote for my French teacher at U-High,” some 1,000 photographic prints, and a wartime message “signed by Marlene Dietrich that I was supposed to give to her husband. It has his telephone number—I was supposed to call him and tell him she was well.”

Morris did not, however, collect prints by the photographers with whom he worked. “When I think of all the Cartier-Bresson prints I’ve thrown in the wastebasket,” he says ruefully, “it’s kind of silly.” During the 1950s and ’60s, when he worked for Magnum Photos, the international photo agency that Cartier-Bresson cofounded, prints weren’t seen as collection-worthy: “We used to offer prints by Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa and others for $25 or $35 apiece,” Morris says, “and nobody bought them.”

While 90 percent of his collection is now at Chicago, Morris held back his Magnum materials; the agency is celebrating its 60th anniversary this year, and he’s often called upon to comment on its early days. He’s also kept a lot of personal correspondence: “I’m now working on a book about my three wives. A lot of men have been married three times, but not so many have been a widower three times.”

Morris’s first wife, Mary Adele Crosby Morris, AB’39, died in 1964, and his second wife, photo editor Margaret “Midge” Morris, died in 1981. His third wife, photographer and children’s book author Tana Hoban, died in January 2006: “I wrote a tribute to her at the time, which gave me the idea of writing a book not just about her but about the two previous wives, who were also remarkable women.”

He fits in work on the book, tentatively titled A Love Letter to My Three Wives, between speaking engagements; meetings of Democrats Abroad France, which he and Hoban helped found shortly after they moved to Paris; travel to visit family and friends; and fielding the many calls and e-mails he gets as someone who knew the greats of an earlier era.

Two prints from that era, inscribed with messages from the photographers, hang above his office desk. The images are icons, the stuff of posters and postcards. In Cartier-Bresson’s Rue Mouffetard, a grinning youngster carries two bottles of wine down the Left Bank market street; in Marc Riboud’s Painter on the Eiffel Tower, a worker relaxes high above the city’s skyline. Both seem fitting images for someone who has happily spent a quarter of his life as an American in Paris.