|

||

|

Features ::

Celestial sphere

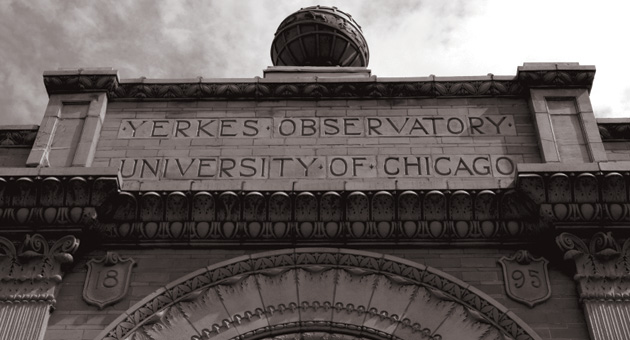

With its apogee as a center of astrophysical discovery now past, the 110-year-old Yerkes Observatory waits to see what’s in its stars.

Williams bay, Wisconsin, on the shore of Lake Geneva, is two hours by car from Hyde Park. Traversing the green-bordered drive that leads to Yerkes Observatory is a trip into another world and time. Set on 77 acres originally landscaped by the Olmsted Brothers, the brown-brick observatory, operated by the astronomy & astrophysics department since 1897, is distinguished by its Romanesque grandeur—and by the 90-foot dome arching skyward at the building’s west end.

Founding director George Ellery Hale envisioned an observatory that was more than a place to house telescopes. With laboratories, darkrooms, mechanical shops, a library, and first-class instrumentation, Yerkes became a magnet for researchers, and its roster is filled with Nobel names: Albert Michelson brought his inferometer to measure double stars, Edwin Hubble, SB’10, PhD’17, photographed faint galaxies, and Subramaniam Chandrashekhar embarked on his study of star-cluster dynamics at Yerkes.

Along with many original fixtures and furnishings, the genius of the place remains. Ghosts seem just around the corner—carrying glass-plate photographs of stars, correcting page proofs from the Astrophysical Journal, slipping out for a picnic on the Great Lawn. Meanwhile, research engineer Jessie Wirth tests an imaging camera being built for NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy. Education-and-outreach coordinator Vivian Hoette prepares for back-to-back June programs, a summer institute for Illinois teachers and a national Hands-On Universe conference. Observatory director Kyle Cudworth, the only astronomy & astrophysics professor now based at Yerkes, writes exam questions for a Spring Quarter course he taught on campus, ASTR 18100: The Milky Way.

Yet in the dim, first-floor hallway that leads up a steep flight of stairs to the 40-inch refractor—once the largest telescope in the world—there’s a sense of suspended animation that mirrors an institution awaiting its next reincarnation. It’s long been agreed that Yerkes’s day as an observational center is past (light pollution, humidity, and low elevation all restrict its reach). But when the University decided the time had come to redirect its Yerkes resources to support other research—while preserving the observatory—agreement proved elusive. This winter, Williams Bay residents spoke out against the University’s proposal, announced last June, to sell 45 acres (including land fronting the lake) to a New York–based developer, and the deal was called off.

In February the astronomy & astrophysics department went back to the drawing board, forming the Yerkes Study Group with representatives from the department and outside institutions. Charged with exploring how to transform the observatory into a regional site for science education, the group, chaired by astronomy & astrophysics professor Richard Kron, has been meeting with a range of stakeholders: local residents, environmentalists, educators, historians, and astronomers, to name a few. “Finding an acceptable compromise path,” Kron has noted, “will be complex and will take time.” Yet he sees important common ground: “In the end, we all want to preserve the observatory.”

In the meantime it’s summer in Williams Bay, and fireflies dance like stars on the Yerkes lawn

Dreams in stone: An ornate facade reflects George Ellery Hale’s vision of an observatory dedicated to astrophysical research—and streetcar tycoon Charles T. Yerkes’s desire to make a splash by funding what was then the world’s largest telescope.