|

||

|

Course Work

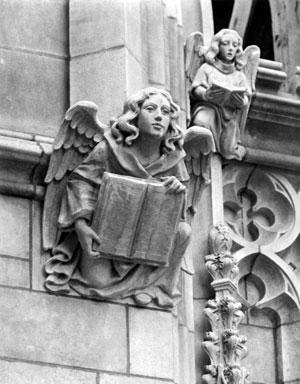

Outside Bond Chapel, angeles and texts; inside, Divinity School students practice the art of preaching

The word made fresh

Divinity School students in Cynthia Lindner’s Advanced Preaching seminar must go beyond chapter and verse.

Would you take some silence?” Cynthia Lindner asks gently. “Maybe some breath with that silence?” The eight Div School students in her Advanced Preaching seminar—four men and four women—immediately bow their heads in prayer. The room falls silent. Outside the Gothic window, open on a warm May afternoon, birds twitter.

On Tuesdays Lindner’s class meets for the first five minutes in Swift 400A, a diagonal room carved out of the building’s northeast corner. Two students are scheduled to preach today, and Lindner, AM’80, DMN’99, must determine the order.

The students come from a range of Christian traditions—United Church of Christ, Disciples of Christ, Mennonite. Jackie Posek is Catholic: “I won’t be a priest, so I won’t be preaching every week,” she explains. “But there are opportunities for women to preach in different settings.” Fern Turner, a former Catholic, is “a newly minted Episcopalian—one month today.”

As for their sermons, “Mine’s sad,” says Posek. “So we can start with sad, or end with sad.” Based on that description, Lindner assigns Posek the opening spot: “Fern, you bat cleanup.”

The class makes its way down four flights of stairs and through a cloister into Bond Chapel. With vaulted ceiling and stone walls, the almost empty nave creates its own echo chamber. The sound was much clearer in the diagonal room with the acoustic-tile ceiling.

“All right, congregation. Take a breath. Center yourself in this space,” Lindner says with a preacher’s cadence. “This is—as are all other grounds—holy ground, my friends. And this is a holy task.”

Posek, seated with the rest of the class in the first few pews, takes a sip from a giant plastic cup and walks to the altar. Lindner fiddles with a video camera set up in the aisle.

“The Lord be with you,” Posek says.

“And also with you,” the class responds.

Posek’s text, on the Resurrection, comes from the First Letter of Paul to the Corinthians. (Lindner and her teaching assistant chose a selection of biblical texts, and students picked theirs out of a hat; they had a month to develop a sermon, using whatever translation they preferred.) “‘Listen, I tell you a mystery,”’ Posek reads. “‘We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in a twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet.’”

She begins her sermon with the same line, delivered in the same calm voice: “Listen. I’ll tell you a mystery, one from my own archives.” The protagonist of her tale is Connor Murphy, a young man she knew at Notre Dame. “He was born to be great,” she says with force. “Tall, dark, and handsome, charming and witty. ... He was custom-made to be one of the good guys on Capitol Hill. Maybe someday he would be our new JFK—with all the charisma and none of the adultery.” But in his sophomore year Connor was diagnosed with leukemia.

The common cultural depiction of life after death—that the dead person is in a better place, or is in heaven looking down at us, or is always with us—is comforting, Posek says. “Unfortunately, this image has no basis in our scriptures.” As Paul explains to the Corinthians, “Resurrection doesn’t take place at each individual person’s death, but rather all at once—everyone—in a moment at the last trumpet. And it’s not a purely spiritual resurrection either. It’s bodily.”

Posek discusses the Corinthians’ skepticism, the Greco-Roman concept of death in their day—that the spirit was eternal but the body was left behind—and her own fruitless search for a pithy explanation of the Resurrection. “I was looking for something that really didn’t exist,” she says, once again quoting Paul: “Listen, I will tell you a mystery.”

She ends with her memory of a high-school gymnasium filled with “500 people who had come to say goodbye to a young man who wasn’t destined to be the next Catholic president,” she recalls. “And I felt empty and aching.” As the service ended, Posek turned to a friend and said, “You know what? I think I believe in the Resurrection.”

Her “Amen” given, Posek returns to the front pew while the other students silently scribble comments.

“Seventeen minutes, 47 seconds,” says Lindner.

“Wow, that’s a long one for me,” Posek replies. “I usually go eight to ten.”

“The ending unsettled me,” says a young man in a pressed blue button-down. “What prompted you to end with that line?”

“Well, that really happened,” says Posek. “For me it encapsulated the fact that my faith is not the way I would design it. It felt illustrative of my faith journey, which has been very messy and full of struggle. But as terrible as that was, God was definitely there.”

A student compliments the sermon’s “smooth feel.” Another says it was Posek’s “most raw, emotionally honest sermon,” but adds, “We could have a long conversation about the theology of the Resurrection. I would say frankly that much of the theology I would find difficult to accept. But bracketing any theological concerns, it was a rhetorically very powerful sermon.”

“My immediate reaction was, ‘Oh no,’” says Lindner. “I hate dead-young-people sermons. It induces pathos, and there must be some happy resolution. But you handled it well.”

Now Turner steps to the front. Like Posek, she wears a T-shirt, thin skirt, and flip-flops. Her text, a reading from the Book of Jonah, is about God’s threat to destroy Nineveh, the capital of Assyria. But when everyone in Nineveh dons sackcloth and ashes, God “repents” and does not destroy the city.

Turner begins by imagining the itchy sackcloth—“probably made of coarse, black goats’ hair”—as well as the hunger and dizziness from fasting. “Nineveh changing its ways was only the second most important part of this story,” she says. “The most important part of this story is that God repented. God repented, a notion that is so perplexing that I have reeled for the last month or so trying to understand it.”

The story would seem to have a happy ending—but not for Jonah, who is angry at God for not following through on his threat. “It may seem as if Jonah is being petty and selfish. How great is it to have a merciful and forgiving God?” she says. “But in truth I understand where Jonah is coming from.”

Then she slips into a personal story, about her joy that relatives were coming to spend Christmas in Chicago. But they were not coming for a joyful reason. The father of the family, a Green Beret, was being redeployed to Iraq. Turner speaks quickly, with controlled fury. She imagines her relative’s stiff military photo flashing on the evening news, “when Katie Couric spends three minutes summing up his life in a matter of sentences and talking about how yet again more American soldiers have died from roadside bombs or sniper bullets.”

“I thought of those that live in the land that once was Nineveh”—Turner pauses—“that is now Mosul.” The anger in her voice shifts; she is near tears. She speaks of her desire for revenge against those who “can no longer separate an ideology from humanity” and the U.S. government, which has sent thousands of soldiers into battle “unprepared, unprotected, and exhausted.”

And yet we cannot be angry like Jonah. “For in this hour of darkness,” she concludes, “we have no choice but to hope that God can see what we cannot, trusting that the others deserve the forgiveness we have been given.”

Turner sits down; Lindner switches off the camera; the students scribble.

“That was a flash of genius, this passing comment—‘Nineveh, which happens to be Mosul.’ That just turned the entire sermon at that moment,” says a man in a red knit shirt. He praises her precise delivery. “There was no shouting, there was no screaming.”

“I yelled in practice,” Turner admits.

Later in the discussion, the same student observes, “Nobody quite knows what Nineveh did wrong.” Turner nods. Researching the text online, she found that “not even the most fundamentalist sites claim to know anything about Nineveh’s sin.”

“You stayed with the text,” notes Lindner. “You could do the Nineveh-Mosul thing well or badly. There are no good guys at the end of the day. Staying with the text made that happen.” Up to this point in the course, she adds, the emphasis has been on texts, not delivery. “Now we need to let the sentences breathe a bit. How did it feel to preach that one?”

Turner shakes her head. As a former Catholic who felt called to ordained ministry, she has just reached the end of nearly three years of struggle, doubt, and uncertainty. “I’m not sure.”

Cynthia Lindner

Required texts for Cynthia Lindner’s Advanced Preaching seminar include Between the Bible and the Church: New Methods for Biblical Preaching by David Bartlett and The End of Words by Richard Lischer. No one translation of the Bible is specified. “In many of our Bible courses, students work with the NRSV (Oxford Annotated Edition) or the Harper Collins Study Bible,” Lindner says. “Oftentimes, if a word in translation has become devalued in our contemporary discourse, choosing another possible interpretation of the original term can yield richer meaning.”

Assignments include an eight- to ten-page paper on “your own (provisional!) position on the relationship of the Bible and preaching” (20 percent of grade), two sermons preached to the class (20 percent each), a presentation on the text for the first sermon (20 percent), and short written responses to classmates’ first sermons (20 percent), answering such questions as “How does the preacher present the text in the sermon—is it quoted, summarized, narrated, paraphrased, enacted?” and “How does the sermon work theologically?” “Are risks taken? Is urgency evident?”

Possible texts for the first sermon included Exodus 3:1–15, Proverbs 4:1–9, Jonah 3:6–11, Amos 5:18–24, Matthew 6:19–34, John 12:1–8, Luke 11:33-36, Acts 17:22–28, I Corinthians 15:50–58, and Colossians 2:8–15. Lindner and her teaching assistant, Tish Duncan, select texts that are either “interesting or difficult—out of time, out of place, or so familiar.” Students choose their own passage for the second sermon, which serves as the final exam.