|

||

|

Anchovies and empathy

Gender studies and English scholar Deborah Nelson analyzes what lay behind some 20th-century female intellectuals’ aversion to sentiment.

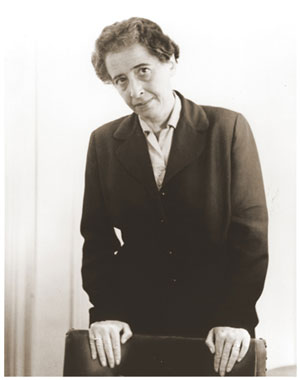

“I knew I had done something wrong in my efforts to please,” author Mary McCarthy said in 1975, delivering a eulogy for her friend Hannah Arendt. She recounted how she had once prepared for a visit from Arendt by purchasing a small tube of anchovy paste, an item McCarthy had seen her friend enjoying with breakfast. When the philosopher spied the item, she pretended not see it. “I had done it to show her I knew her,” recalled McCarthy. Yet even after three decades of friendship, Arendt “did not wish to be known.”

Arendt’s detached tone stemmed less from a lack of empathy, Nelson says, than from a sense of moral responsibility.

Such wariness of intimacy, says Deborah Nelson, associate professor in English and the humanities, illuminates the extreme end of a mindset prized by Arendt, McCarthy, and other trailblazing female intellectuals. They include essayist and activist Susan Sontag, AB’51; writer Joan Didion; and photographer Diane Arbus, famed for her gritty portraits of transvestites, prostitutes, and other social pariahs. In her book Tough Broads, which she hopes to publish next summer, Nelson investigates how these women eschewed empathy to confront 20th-century tragedies from the Holocaust to 9/11 in what they deemed the most responsible, and ultimately most moral, light.

To these “tough broads,” compassion had no role in public life. Instead, explains Nelson, “antisentimentality meant lucidity, a faithfulness to observable reality” that could be obscured when emotion entered the picture. Arendt, who taught in the Committee on Social Thought from 1963 to 1967, decried compassion’s “devastating” effects in her book On Revolution, which analyzed how the French and American Revolutions influenced political freedoms. Individuals, she believed, must rid themselves of emotional involvement when confronting unpleasant realities if they wished to effect social change. In Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, her chronicle of Adolf Eichmann’s war-crimes trial, she characterized the case against the Nazi official as “built on what the Jews had suffered” rather than “what Eichmann had done.” Arendt’s argument on the “banality of evil”—her observation that Eichmann’s actions were not based in anti-Semitism but in a basic desire to do his job—scandalized readers, critics, and fellow Jews, who found her dispassionate tone inappropriate and offensive.

Almost four decades later, Sontag came under similar fire when she urged Americans to reconsider how U.S. foreign-policy decisions may have precipitated the 9/11 attacks. As public sentiment rallied around the Bush administration, Sontag pushed for less “self-congratulatory” solidarity and more critical thinking. “Let’s by all means grieve together,” she wrote in the September 24, 2001, New Yorker. “But let’s not be stupid together.”

While writers and artists of both sexes have long struggled to find the correct tone for addressing public catastrophes, says Nelson, women such as Sontag and Arendt were more apt to be condemned as heartless not only because of their tone but also because of their gender. By keeping emotion out of their politics, they failed to meet expectations of female empathy. “For Norman Mailer, this was never going to be an issue,” says Nelson. Yet the women’s emotional distance, she argues, was not “a glib failure of empathy” but a commitment to objectivity and a sense of empathy’s “complications and compromises.”

Both Arendt and Sontag believed the commiseration and collective healing favored by progressive postwar social movements made individuals vulnerable to single-mindedness. One means of protection against such delusion was avoiding specific political and ideological movements. “I’m not sure they would welcome this gesture,” says Nelson of her efforts to identify the tough broads’ common philosophical thread. “I’m asserting their connections, in some ways, against their will.”

She began assembling the links while working on her first book, Pursuing Privacy in Cold War America (Columbia University Press, 2001), which explores the relationship between confessional poets such as Anne Sexton and Robert Lowell and postwar Supreme Court decisions such as Roe v. Wade that redefined cultural notions of privacy. Studying Lowell’s poems about his divorce from novelist and critic Elizabeth Hardwick, she read Hardwick’s Seduction and Betrayal, a critical look at female writers and literary characters. Nelson was struck by the detached tone the author used to comment on emotion in contemporary literary culture. Then she discovered similar themes in the works of McCarthy, Arbus, and others.

Even before she began her research, Nelson was inspired by one of the women in her book. Between earning her English bachelor’s degree from Yale in 1985 and enrolling in a doctoral program at the City University of New York Graduate School and University Center in 1991, she did promotions at the Sporting News and taught English at Shanghai’s Fudan University. During this time, she read Didion’s essay “On Self Respect,” a “quintessential tough-broads argument” that self-respect emerges in the moments when individuals fearlessly confront their failings and weaknesses. It was “a bad version of myself she was criticizing,” recalls Nelson, “the person who can’t answer the phone because she won’t be able to say no to whatever is asked of her, whether it’s a party or a job.” She hoped Didion’s version of self-respect would cure her. “It didn’t, of course,” says Nelson. “People are more complicated than the young Joan Didion and I imagined.”

Nelson sees other weaknesses in the women’s ideology. Director of the University’s Center for Gender Studies, she points out that confessional, emotional literature has played a critical role in highlighting many gay-rights and feminism issues. “I’m not anticonfessional at all,” says Nelson, who takes issue with Didion’s, Arendt’s, and McCarthy’s staunch rejection of emotion in public life. “Under the guise of coolheaded dispassion,” she says, “they are sometimes very extreme.” Still, their commitment to objectivity—an aesthetic approach Nelson believes is “somewhat invisible to our collective memory of the period”—sheds important light on how writers grappled with the 20th century’s ethical and moral quagmires.

As for the personal intrusion Arendt felt when McCarthy offered the anchovy paste, Nelson can’t help but see Arendt’s reaction as excessive. “This woman’s been your friend for 30-some years,” she says. “Just give her a break.”