Balance sheet

As Chicago’s upward trajectory and the global economic crisis intersect, the University lowers budgets but not expectations.

By Mary Ruth Yoe

Graphics by Allen Carroll

Institutionally speaking, Chicago spent 2007–08 on a roll, breaking University records for fund-raising progress ($376 million) and College applicants (12,409). Both records have already been surpassed in 2008–09—the year that has witnessed the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. As the market and the endowment dropped, the need for significant budget cuts became apparent. Rather than decree one-size-fits-all measures, such as across-the-board reductions or hiring freezes, President Robert J. Zimmer and Provost Thomas F. Rosenbaum began to work with vice presidents and deans on an even more delicate balancing act: determining how to cut budgets over the next two years while strengthening investments in key areas. Despite “the profound global financial and economic dislocations,” Zimmer wrote in a December e-mail to alumni, Chicago must continue to build on its institutional momentum, “to plan with ambition and to pursue our most important priorities to the extent possible in these challenging times.”

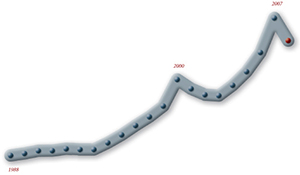

The long view

Twenty years in the life of the University’s endowment are sketched above, beginning in 1988 at $898 million. A history of the endowment, investment philosophy and policy, and information about how the funds are managed are available at the Office of Investments Web site: investments.uchicago.edu.

How challenging? In a January 15 e-mail to Chicago faculty, staff, and students, Rosenbaum estimated that during the first half of fiscal 2009, the value of the University’s endowment, which reached $6.63 billion on June 30, 2008, had “declined on the order of 25 percent, a magnitude similar to that experienced by other leading universities.” Although his readers could do the math—the endowment was now valued at about $5 billion, or slightly above fiscal 2006 levels—Rosenbaum, like other University officers and administrators, shied away from exact figures, a hesitation prompted by the market’s continuing volatility and by the long reporting lags for some asset categories.

The downturn created other revenue and expenditure strains, including greater need for student financial aid, more competition for federal funding, a drop in patient-care revenue at the Medical Center, and higher costs of borrowing for construction. “The bottom line,” Rosenbaum wrote, “is that we must take decisive action to reduce our costs.” Each unit must trim its fiscal 2009 expenditures, with administrative units shouldering proportionally greater cuts (from 3 to 9 percent) than the academic units (2.5 to 5 percent). Taken together, Zimmer told a Student Government roundtable in February, the cuts will shave $130 million to $150 million from the joint University–Medical Center budget by the start of fiscal 2010.

“All units are being asked to share the burden,” Rosenbaum said in a February interview, “and have responded seriously and well” to the dual challenge of cutting costs—finding ways to boost efficiency, to reduce or eliminate lower-priority activities, and to increase revenue when feasible—while continuing to invest in their key goals. Because units have “flexibility in addressing the budget cuts in accord with their different priorities,” Rosenbaum said, “budgets will change in different ways in different parts of the University.”

When less is more

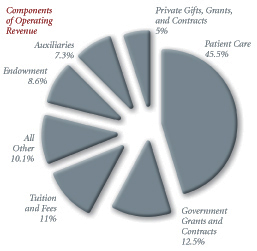

Although the downturn has affected higher education across the board, institutions that fund a large share of their annual operating budget with endowment payout face the most immediate pressures. Unlike many of its peers, Chicago’s reliance is relatively small: 8.6 percent in fiscal 2008.

Not all budgets will go down: “An additional consequence of priority setting is that there will be increased investments in some areas—for example, undergraduate and graduate financial aid, facilities services—offset by more severe reductions in other areas.”

The Medical Center is one of those areas facing severe reductions. In a January 9 memo, Medical Center CEO James Madara announced the need to cut $100 million from the center’s $1.5 billion budget by the start of fiscal 2010. The 7 percent reduction reflects a decrease in patient volume, drops in endowment and investment income, and a backlog of unpaid Medicaid billings. The economic circumstances, Madara wrote, “compel us to accelerate” plans for a “more fully integrated” Chicago BioMedicine (CBM), an umbrella organization formed in 2006 to unify activities in patient care, biomedical research and education, and community health. As a first step in that acceleration, the responsibilities of 15 senior-management positions were consolidated into other leadership roles, and the positions themselves eliminated. Madara cautioned that more reductions, by layoff and attrition, would follow.

Those layoffs came February 9, as 450 employees, about 5 percent of the CBM workforce, learned that their jobs were gone. Other changes—a loss of 30 inpatient beds and a reorganization of the emergency department—will leave CBM smaller but more focused on complex-care specialties such as cancer, neuroscience, and advanced surgery. Thus, Madara said, construction of the New Hospital Pavilion, scheduled for 2012 completion, will go forward, and the Medical Center’s Urban Health Initiative, an effort to strengthen the community health-care network on Chicago’s South Side, will remain a priority.

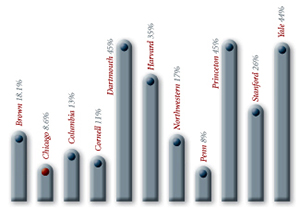

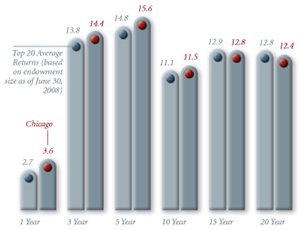

How Chicago stacks up

Compared to returns of peer institutions, Chicago’s endowment—98 percent of which is invested in the Total Return Investment Pool (TRIP)—did well in fiscal 2008. Over the past 20 years, its mean performance relative to the top 20 endowments also has been strong.

FACED WITH TOUGH CHOICES, Chicago is hardly alone. According to a survey prepared for the National Association of College and University Business Officers by TIAA-CREF and the Commonfund Institute, between July 1 and November 30, universities with $1 billion-plus endowments averaged losses of 20 percent—a bit better than the general average of 23 percent. Chicago’s estimated losses are slightly higher, but there is a saving grace: “For our size operation,” explains Rosenbaum, “we are relatively under-endowed. This is generally a bad thing, but in terms of dependence on endowment payout to meet the operating budget, we are therefore less dependent.”

Ranked 11th nationally at the end of fiscal 2008, the University’s endowment reached less than one-fifth the size of No. 1 Harvard’s, then at $36.9 billion. At the same time, payout accounted for 8.6 percent, or almost $231 million, of last year’s operating budget of $2.68 billion, a figure that includes the Medical Center. It’s a smaller slice than is the case for many of Chicago’s peers (see “When Less Is More”). In fiscal 2009 Yale’s endowment underwrote 44 percent of operating costs. Harvard’s covers 34.5 percent of the annual budget, with the portion varying by school and unit—from a low of 13 percent to a high of 83 percent. Harvard’s largest unit, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, relies on endowment payout for almost 60 percent of its funding.

The University’s endowment consists of about 2,700 individual accounts, each with its own restrictions regarding the income’s use. Although tracked individually—to ensure that donors’ wishes are honored, principal is kept intact, and payout to a program or unit reflects the number of “shares” an account owns—98 percent of the accounts are merged into a single fund known as the Total Return Investment Pool (TRIP).

The Office of Investments manages the portfolio allocations within targeted ranges approved by the Board of Trustees Investment Committee (ten trustees and alumni with institutional-investing expertise). The TRIP portfolio emphasizes equity and equity-like investment in its target goals: 34 percent in private equities (11 percent from the United States, 11.5 percent international developed markets, and 12.5 percent international emerging markets); 13.5 percent private equity; and 33.5 percent absolute-return assets (a.k.a. hedge funds). As protection against the market, the remaining 18 percent is targeted for real estate, natural resources, fixed-income assets, and cash.

Where funds come from

After deducting the cost of scholarships, tuition and fees contributed 11 percent of Chicago’s revenue in 2008—just below the 12.5 percent contributed by federal grants and contracts. For more detailed information, see the University’s 2008 annual report: uchicago.edu/annualreport.

Like TRIP’s investment allocations, the endowment-payout policy, adopted by the trustees in 2005, works to balance current and future needs. Its long-term goal is a payout rate of 5 percent, which assumes the endowment will grow by 8.5 percent and inflation by 3 percent. The formula limits annual spending to between 4.5 and 5.5 percent of TRIP market value—averaged over 12 quarters and lagged by a year. Averaging and lagging help smooth market ups and downs, insulating annual budgets from similar bumps. Although 2009’s losses dwarf those of TRIP’s last three red-ink years (down 8.2 percent in fiscal 2001, 7.1 percent in 2002, and 1 percent in 2003), the formula still helps cushion the blow.

Three other revenue streams add to the uncertainty factor. Patient-care revenue contributes the lion’s share of Chicago’s consolidated budget—45.5 percent last year. But patient volume is dropping as people with higher copayments—or without jobs or insurance—delay procedures. With 37 percent of its patients covered by Medicaid (almost twice the national average for teaching-and-research hospitals), the Medical Center was hurt as Illinois, caught in its own budget woes, slowed Medicaid reimbursements, which cover 80 percent of the cost of care.

Sponsored research accounted for the next largest share of last year’s budget. Chicago attracted a record $424 million in research funding in 2008. Nearly 80 percent—enough to underwrite 12.5 percent of the operating budget—came from federal grants and contracts, the rest from foundations, corporations, and other sponsors. Researchers in the Biological Sciences Division received 66 percent of the total awards; the Physical Sciences Division, 14 percent. Although foundation and corporate funding may drop, there’s some cause for optimism: “Most grants are multiyear and often renewable,” Rosenbaum said in early February, so major changes aren’t expected: “With the stimulus package, there may even be increases in federal support of research where University faculty should be able to compete successfully.”

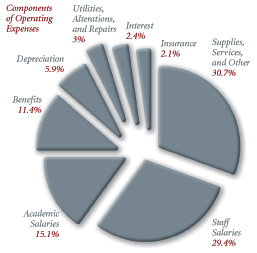

Where funds go

Education, health care, and research have always been labor-intensive enterprises, and Chicago’s yearly operating expenses reflect that. More than half of the University’s 2008 budget—55.9 percent, or $1.45 billion—went toward academic and staff compensation and benefits.

In fact, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act includes $10 billion for National Institutes of Health–sponsored research and laboratory renovation, while the National Science Foundation has received $3 billion for sponsored research; in 2007 those two agencies provided 60 percent of Chicago’s grant money. Researchers in the life and physical sciences will see an infusion of research funds, Scott Sudduth, the University’s associate vice president for federal relations, told the Chicago Maroon: “The NIH has an enormous backlog of faculty proposals that received high marks in peer reviews but didn’t get funding,” including some from Chicago.

Tuition and fees (minus the cost of scholarships) make up 11 percent of the budget, and declining family wealth—as homes, retirement accounts, and investments lose value—affects both tuition income and financial aid. When 2009–10 tuition and fees are set later this spring, the increase will likely fall below the historical average increase of 5 percent. At the same time, Rosenbaum emphasizes, “we remain fully committed to need-blind admissions and working with students who are facing changed financial circumstances.”

About 45 percent of Chicago undergraduates receive need-based aid. As need awards go up, Director of College Aid Alicia Reyes told students in early February, the number of merit awards may drop. Some graduate and professional programs will meet increased need by admitting fewer students (see “Back to School”). A tighter credit market for student loans, especially for international students, is another concern. At Chicago Booth, where 34 percent of the Class of 2009’s full-time MBA program come from abroad, administrators have been part of a University-wide effort to help students who can’t secure U.S. guaranteed loans at competitive rates; the goal is to have at least one program in place before fall.

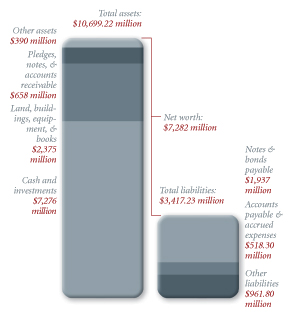

In the balance

Despite a weakening economy, the University’s net assets (cash/investments, land, buildings, equipment, and books lead the list) grew in fiscal 2008—helped by an increase in pledges and other non-operating gifts of $237.02 million from alumni and other donors.“IT’S A HIGH-WIRE BALANCING ACT,” Nim Chinniah, Chicago’s vice president for administration and chief financial officer, acknowledged in January. “How do you demonstrate caution and responsiveness with a sense of confidence?” Meeting with a group of University administrators, Chinniah and Kermit Daniel, AM’86, PhD’93, vice president for financial strategy and budget, said planning for fiscal 2010 and beyond assumes a downturn of three years, the worst since the Depression, but they deemed Chicago “fortunate to be facing the crisis from a position of strength.”

Daniel took up his new post last fall, “almost to the day that the collapse occurred.” After a decade as a corporate strategist, he was struck by the University’s lengthier definition of long term: “ten, 20, even 30 years.” At the same time, he found an “intense focus on mission. Mission guides behavior. You can walk into almost any meeting, on any topic, and you can hear mission being appealed to in making or trying to come to a decision.”

The campus-wide planning process that President Zimmer began in 2006 to identify and to address strategic opportunities and challenges has also provided a mission-focused framework on which to base financial scenarios and choices, Chinniah said: “We’re planning for the long term and executing for the short term.”

Campus construction is a case in point. In December the University issued $425 million in tax-exempt bonds to fund a number of capital projects. Construction on the Joe and Rika Mansueto Library and the Reva and David Logan Center for Creative and Performing Arts, scheduled to open in 2010 and 2011, respectively, continues, as does planning for other buildings. Decisions to delay a project will be made as each one reaches checkpoints at the concept, design, and construction stages, based on the financial situation at the time.

“There’s a good process in place for making decisions,” Chinniah stressed, one that sees the economic downturn not simply as a financial exercise. “Although the numbers are important, this is not a numbers game.” It’s also an opportunity to make the right decisions—a time, as the president wrote in December, “to continue to plan with ambition.”

Return to topWRITE THE EDITOR

DISCUSS THIS ARTICLE

E-MAIL THIS ARTICLE

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

RELATED READING

- Momentum and Milestones (The University of Chicago 2008 Annual Report)

- Messages from University officials and other materials about the U of C's response to the economic crisis