Data Sets

Jason Salavon churns raw data through computer programs to make distinctive art.

By Brooke E. O’Neill, AM’04

Photography by Dan Dry

“Wow, it’s such a tiny screen,” says Jason Salavon, peering at the old Macintosh he used to create his first digital artwork. It was 1993, and he was a studio-art major at the University of Texas at Austin. With that computer—now shelved in his Hyde Park Art Center studio—and a dot-matrix printer, he produced a 300-page book of repeating black-and-white patterns. Photoshop was still in its infancy, and there were “no real tools” to create this sort of artwork, so Salavon, a computer-science minor, designed his own. Intrigued by the idea of “having software autonomously aid and produce work almost infinitely,” he programmed his Mac to generate images while he slept. He’d “wake up in the morning to 30 surprises.”

In technology Salavon had found his muse. Since then he’s used custom-made software to create art from all kinds of material: U.S. shoe-production data, Playboy centerfolds, the IKEA catalog. When Salavon joined Chicago as an assistant professor of visual arts in 2007, he also became the only humanities faculty member with an appointment in the University’s Computation Institute. His visual/technological combinations, exhibited in solo shows for the past 16 years, have earned Salavon audiences beyond the gallery and academic crowds. In February he completed a three-year commission for the U.S. Census Bureau, designing an installation at its headquarters in Suitland, Maryland. Mapping more than two centuries of population data from roughly 6,000 U.S. counties, Salavon sculpted the statistics into a 40-foot-long, 10,000-pound piece—part abstract mural, part video animation. The goal, he says, was to “take this raw material and treat it as a plastic form.”

To realize his visions, Salavon uses C and C++ programming language, 3-D modeling tools, and other self-created software. “Data in its nature has beauty,” he says. Whether the concept involves demographic stats or pop culture, he never neglects aesthetics. “A viewer will often walk in and not know anything about how the piece was made or the backstory,” Salavon says. “So if it can’t stand by itself as a visual object, it probably won’t pass the test for me.” This interplay between art and technology is an ongoing theme in his work: “There’s real meat on those bones as far as the tension between an autonomous mechanical process and the more traditional human creative process.”

Salavon’s amalgamations of everyday images such as yearbook photos or house snapshots in real-estate listings attest to this complex relationship. For these pieces he selects a series of photographs, such as 100-plus single-family homes for sale, and then writes code to overlay the images and gauge the mathematical “average” of the set. The result is an impressionistic composite that reveals the norms of the whole. In averaging Seattle homes, for example, a gray sky emerges, whereas the Los Angeles/Orange County compilation is awash in blue. Many viewers say the images—unedited by Salavon—“look like Monet or Turner.”

Salavon started blending art while road-tripping across Texas in his early 20s. The radio blaring in his VW Bug, he thought about what makes a hit song, trying to merge No. 1 songs in his head. Although the musical analysis led to only one piece—an audio CD blending 27 covers of the Beatles hit “Yesterday”—it launched Salavon into a multiyear, multiproject investigation combining photographs that resonated with him personally. His yearbook series, for example, averages all the photos of his high-school graduating class into two prints—one using the men, another with the women—called The Class of 1988 . He also did a set for his mother’s graduating class, The Class of 1967. His series Emblem began by choosing films—2001: A Space Odyssey , Taxi Driver , and Apocalypse Now—“that my dad showed me when I was probably too young” to understand them.

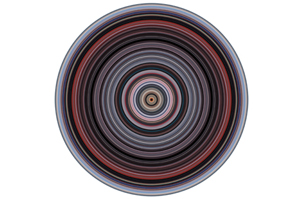

Emblem (2001: A Space Odyssey) 2003. To create this 48” x 48” digital photograph, Salavon designed an algorithm to average the colors in each frame of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Organized in concentric rings, the frames follow the narrative, starting in the center. Along with Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driverand Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, this piece is part of Salavon’s Emblem series. All three, he says, are by “auteur filmmakers who are sort of demanding and control-freakish.”

The Late Night Triad 2003. This three-part video installation features The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, Late Night with Conan O’Brien, and Late Show with David Letterman. Salavon recorded 64 nights of opening monologues, then averaged each show’s material. The blended videos reveal the sequences’ precision, with a cutaway to the band or Conan’s trademark jump occurring at nearly the same time every night. They also highlight the hosts’ differences. “Leno is such a whirling dervish on stage that his figure never coalesces,” says Salavon, while Conan is regimented: “You can actually see his facial features all lock in.” Letterman falls in between.

The Top Grossing Film of All Time, 1x1 1997. This photographic piece took all 336,247 frames of the hit film Titanic and “smeared each mathematically to a solid color.” Organized in horizontal rows from top to bottom, the frames read from left to right, following the film’s narrative sequence. What remains, says Salavon, is the “visual rhythm” of the film, parsed out in pure color. Leonardo DiCaprio’s “I’m the king of the world!” scene comes across in bright tones, while the sinking ship plunges into gloomier swatches. The Whitney Museum bought the piece, and DiCaprio purchased one of five limited editions for his personal collection.

Field Guide to Style & Color 2007. Debuted at a 2008 Columbus Museum of Art solo exhibition, this 374-page book reformats the entire 2007 IKEA catalog as solid color patterns. The world’s largest furniture manufacturer, the Swedish company distributed an estimated 198 million copies of its catalog each year and claims it’s the most published print object in the world (the Bible comes in second). Salavon, who wanted to explore the relationship between catalog designer and fine artist, was struck by how the pages of his pure color version resemble “certain abstract paintings.”

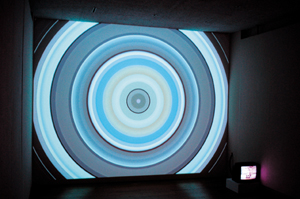

Everything, All At Once (Part III) 2005. Using a live feed (bottom right), this video installation converts each frame of television content into a solid-color circle. The frames appear as a series of concentric rings, which shift when the channel automatically changes every 30 seconds. The abstract rendering, says Salavon, raises questions about how television works. During a certain car commercial, for example, the circle pattern becomes a pronounced black-white-black-white series of rings. “It’s got to be some little subtle hypnosis thing they put in,” he says. “It’s got to be consciously there.”

Raised in an “artistic, hippy household” in Fort Worth, Texas, he grew up watching his father, a “classically trained, ’70s-style surreal artist,” juggle a day job with painting at night. Although the young Salavon sketched and painted, he never wanted to be a professional artist—until he took a college drawing class and “totally got bit by the bug.” His first foray into digital art, the 300-page book of black-and-white patterns, confirmed his new direction. “My consumption with the process,” recalls Salavon, “overwhelmed another part of me that was like, ‘Wow, do you really want to go through what your dad went through?’”

He decided to chance it. Today his digital photography, video, and multimedia projects have been shown around the world at venues such as Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art and New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. What Salavon describes as his “technology-informed, pop-culture–informed blend” may even be changing how such institutions think about art. In December 2007 Washington’s National Portrait Gallery acquired Salavon’s The Late Night Triad , a video triptych showing 64 nights of monologues by talk-show hosts Jay Leno, Conan O’Brien, and David Letterman. It was the museum’s first electronic artwork in its permanent collection.

With possible solo shows in Chicago, Seattle, and New York on the horizon, Salavon looks forward to growing his diverse portfolio. “Every project can be significantly different,” he says, noting that most of his concepts are easier to describe than to execute. Yet thanks to open-source software—many programmers make their work available for free use—and multiple ways to create his own, he relishes each new project as a problem to be solved. “It’s just a matter of figuring it out,” he says. His computer literacy is also the reason he insists his students learn at least some programming, even if they don’t think they’ll use it. “Just a little knowledge of how things work under the hood,” he says, “can enable you to have a broader sense of what’s possible.”

Return to top