Literary agents

Three young-alumni authors have gotten big-time book deals, thanks to agent Stephen Barbara.

By Ruth E. Kott, AM’07

Photography by Dan Dry

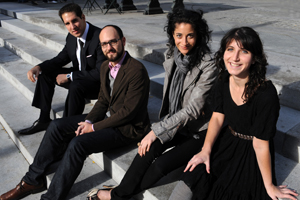

New York’s publishing world has been kind to Barbara, Munson, Schechter, and Sales.

Stephen Barbara knew Laura Schechter in the College, but only slightly. “I remember her chiefly,” says Barbara, AB’02, “as one of the first girls to have a cell phone at the University.” Now they have a close professional relationship—Schechter, AB’04, is about to publish her first young-adult novel, Before I Fall (HarperCollins), in March, and Barbara is the literary agent who got her a quarter-million-dollar, two-book deal.

It’s been a big U of C year for Barbara, who joined New York City’s Foundry Literary + Media in January 2009. After Schechter, he signed two other young-alumni authors with major publishers. Buzz about a debut adult novel by Sam Munson, AB’03, The November Criminals (due in April 2010), led to a New York Observer story; after an auction, it was signed to Knopf Doubleday. Barbara also secured a two-book deal for first-time author Leila Sales, AB’06, whose young-adult novel Wayward Girls (Simon & Schuster) will be published in fall 2010.

The Chicago connections aren’t a coincidence. When Schechter, then an editorial assistant at Penguin’s Razorbill imprint, first contacted Barbara in 2007, she used that link to get a meeting. She wasn’t thinking of her own writing yet; she wanted to connect with him so that he might send her new projects. “The publishing industry is extremely hierarchical,” says Schechter. Agents don’t want to talk to editorial assistants; Barbara was the only agent who responded to her request.

For their first meeting they went out for drinks. As an aspiring editor, Schechter says, “I had taken him out. That’s how the power dynamic is.”

At the time Barbara, who grew up in Connecticut, was an up-and-coming agent at the Donald Maas Agency. He was attracted to the New York publishing world, partly because of the glamour—it wasn’t quite the world made famous by the letters of Edmund Wilson and Vladimir Nabokov, he says, but the city’s vibrant social scene excited him—and also because of the uniquely New York attitude, which he sums up in a word: “toughness.”

Barbara has learned to recognize good writing: he studied literary criticism in the College and was a cofounder and coeditor of the literary journal Euphony, which he started as a second-year. That same year he met Munson, a first-year and a poet, while they were waiting for a bus outside the Shoreland. Barbara invited Munson to send him some poems. Says Barbara, “He turned out to be probably the best poet we worked with at the University of Chicago.”

After graduating, Munson continued to send pieces to Barbara, who had become a close friend. But it wasn’t until the end of 2008 that Munson sent him The November Criminals.

The book is less poetry and more essay. An application essay, in fact, addressed to the University of Chicago’s admissions committee. The question: “What are your best and worst qualities?” The answer comes out in a 240-page rant about life as his high-school classmates’ drug dealer and his plan to play detective to figure out who murdered one of the boys in his grade.

Munson began thinking about The November Criminals while working as online editor for Commentary magazine—his grandfather, Norman Podhoretz, is the magazine’s former editor. He was “bored at work,” he says. “I thought I’d give it a go.”

Although the narrator, Addison Schacht, isn’t based on anyone in particular, says Munson, who left Commentary in 2008 to freelance, Addison displays certain elements of Munson’s own personality, amplified—skeptical, negative, angry. Barbara’s pitch letter compared Munson to Chuck Palahniuk, famous for writing aggressive, self-destructive male protagonists. In fact, Palahniuk and Munson now share the same editor, Gerry Howard. It was quite easy, Munson says, for him to get into Addison’s head (see Open Book for an excerpt).

Schechter’s protagonists, on the other hand, occupy her head. Schechter, who goes by the pen name Lauren Oliver, hears her characters speaking to her “in a true schizophrenic way,” she says. “It’s not like they tell me to do things. They just start narrating their stories.”

It happened with her narrator from Before I Fall, a teenage girl who dies in a car crash and keeps reliving the day of her death. The narrator, Samantha, starts off being “intensely unlikable,” Schechter says, “casually cruel in a way that kids can often be with each other. She’s self-absorbed, and she’s petty.” The story follows Samantha’s emotional growth.

Before the novel was written, Barbara recalls, Schechter pulled him aside at a networking event, saying, “‘I’m about to pitch you a book right now.’ She said it was like The Lovely Bones meets Groundhog Day, which I thought was such a Hollywood pitch, and I thought it was great. And then it was exactly right.”

The small world of New York publishing also brought Barbara together with Sales. Schechter, who had worked with Sales at Penguin, introduced the two at a party this past winter. “I had almost finished a first draft” of Wayward Girls, says Sales, and she mentioned that she was thinking about publishing a novel. Barbara told her that he wanted to read it—“No, seriously, I do,” she recalls him saying, when she pshawed him at first. After revising it several times with help from other editors, including Schechter, she sent him the manuscript August 3. “He called me on August 5,” says Sales, “and said that he had read it and wanted to represent it.” As an editorial assistant, Sales knew how rare that was: “Nobody reads that quickly.”

Wayward Girls, says Barbara, “is a funny, smart debut.” “Funny” was what Sales was originally going for. A former humor columnist at the Maroon (and 2004–05 Magazine intern), she started writing a collection of brief humor pieces. “Eventually,” she says, “there wound up being a plot,” about best friends at a Boston all-girls’ prep school.

All three of Barbara’s Chicago clients wrote their debut novels before turning 28. Publishers are attracted to these authors, says Barbara, because of their potential. If their first book, written at age 25, is impressive, imagine what they could write when they’re 30, 40, or 50.

For now, Sales hopes to keep writing young-adult fiction. “Maybe when I’m older,” she says, “I will be more interested in what old people think about. I guess I have wisdom on the teen years since I’ve lived through them, but I don’t have any sort of wisdom on what it’s like to be 30.”

Schechter hopes to stick with young adult as well. Having already written a second novel and gotten another two-book deal from Harper, she left Penguin and now writes full time. And the “power dynamic” between Barbara and her has perceptibly shifted. Once the editorial assistant who paid for drinks, she first noticed the shift when Barbara agreed to represent her: “We went to Olive’s, this fancy-schmancy breakfast place by Union Square,” says Schechter. “At the end of the meal, out of habit, I went to reach for my wallet. But he was like, ‘No, no. Now I pay for you.’”

WRITE THE EDITOR

E-MAIL THIS ARTICLE

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

RELATED READING

- "Agent spotlight: Stephen Barbara"

(Literary Rambles blog, Apr. 2, 2009) - "Why do young male writers love icky, tough guy deadbeats?"

(New York Observer, Jan. 27, 2009) - "Sam Munson, grandson of Norman Podhoretz, taking debut novel to market"

(New York Observer, Jan. 16, 2009) - "Interview with Stephen Barbara"

(Manuscript Mavens blog, Aug. 3, 2007)