A novel approach

Presumed dead by the Alumni Association, an alumnus shares some life benchmarks, told through four writers’ lenses.

By Alan M. Charlens, SB’58, PhD’63

Illustration by Brett Affrunti

When a friend mentioned the game tickets, brochures, and other mail he received from his alma mater, Al Charlens suddenly realized, “I never get a thing” from Chicago. He called the Alumni Association. “We have you listed as deceased,” a young man told him. “Restored to living” in the alumni database in 2004, Charlens, the son of Henrietta Charlens, PhB’31, attended Hyde Park High School and after college briefly studied acting at London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. In 1969 he moved to San Diego, where he co-owned a surf shop. A retired prison psychologist for the California Department of Corrections, he’s semiretired from running his own theater and continues to act in plays and films.

Charlens, 73, wrote to the Magazine after reading “The Fighter Still Remains” (July–Aug/09), about Mark Allen, AB’01, a boxer who overcame drug and alcohol addictions. Charlens too had boxed in his youth. Instead of sending an Alumni News item to update classmates on his life, he penned an essay in four parts. He channels the writers Ernest Hemingway; Max Shulman, who created the character Dobie Gillis and whose syndicated humor columns appeared in the Maroon when Charlens was a student; Isaac Bashevis Singer, whose 1967 short story “The Lecture” contains a reminiscence of Poland; and Bernard Malamud, from whom Charlens borrows scenes from the short story “My Son the Murderer.”

He begins with Hemingway.

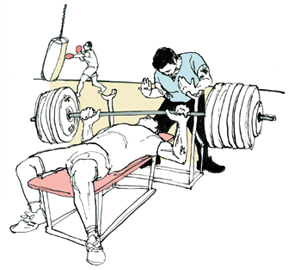

“Today is the day.” The spotter said this not looking at me as we walked into the gym together and walked up the stairs to the weight room, past the machines with gleaming chrome for leg lifts, and into the small room where the heavy weights were kept, and it was good. In those days they weren’t called free weights, just weights, and we took our position, I on the bench and he behind me in that clean, well-lighted room where we had trained. I put the carbonate of magnesium on my hands. We didn’t use gloves back then, just the chalk, and kept our fingernails short, so as not to dig into our palms.

“Benching 300 pounds by age 50 is important to you,” he said, “especially for where you work.”

“The prison,” I said, and it was good that he understood. “A prison psychologist who can do that.” I didn’t finish but lifted the bar off the standards and did it, with the young spotter shouting, “Push! Push!” as encouragement. I did two more sets, sitting up between.

“When are you 50?” he asked, and I knew he knew, but he just wanted to hear it again.

“Two more days.” He nodded slightly and prepared for his own workout.

“It was 315.”

“What was?”

“You benched 315. Between sets I put an extra five and two-and-a-half on each side. Your last set was three hundred and fifteen pounds.”

“It felt good.”

I was sitting in my office at the prison, thinking of the distant acacia trees and making plans to worm my dog, when I was approached by a prison lieutenant, loose and lank.

“Hello,” he said. “My name is Loose Lank.”

“And mine,” I replied, “is not.” Well, we had many a laugh and cheer over that, and when we were through laughing and cheering, he told me the reason for his visit.

“I hear tell you are planning to run psychotherapy groups for the prisoners.”

“Right! Quite right!” I cried.

“You know that upon release they re-offend at a rate of 70 percent to 90 percent. Recidivism—return to custody.”

“RTC,” I said, taking inordinate pride in my mastery of at least one prison acronym.

“I see you can take inordinate pride in the mastery of at least one prison acronym,” said Lank as he clapped me on the back.

I tugged my forelock and bashfully kicked in the sand with my toe. I squared my shoulders and said with quiet confidence: “I shall conduct such groups natheless. Perhaps some good shall ensue.”

“Meglio per voi,” he said, and I responded with, “Tante grazie,” which was strange, neither of us being Italian.

We clasped hands and stood there for a long moment, not trusting ourselves to speak. At length he sniffed and said, “I smell tear gas and hear sirens and whistles. Mayhap my presence is needed elsewhere,” and he turned and walked off toward a brake of plane trees.

“Be wary of the plane trees,” I warned. “Their propellers are quite sharp.”

With that he fell into such a fit of laughter that he had to be placed under sedation, where he is to this day. And run groups I did, and I kept records, and the RTC rate was 30 percent.

A synagogue had asked me to sing the Kol Nidre prayer on the eve of Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish year. I took a room in a nearby hotel to rest and prepare for the evening, taking a final drink of water and a small brandy. This would be the last of anything I would have for 25 hours as I would observe the fast day.

Proceeding to the synagogue, I stayed outside for a while, watching people collecting. How different from Poland. There were no hats on the men, no long black coats, and no long beards, but rather, if at all, neatly trimmed goatees. They reached in the pockets of their well-tailored suits and put on small yarmulkes. And the women: no shawls, no heavy shoes, but rather beautiful clothes, carefully coiffed, and with multicolored fingernail varnish.

I entered the synagogue. At the back was a table with prayer books; no candles, no plates for donations. The latter would be handled silently, with little pieces of paper in envelopes.

The rabbi motioned me to come forward. He was taller than me, and slender, and when we first met I said that he was younger than my son, and he smiled and said he hears that all the time.

The sun was very low, and in minutes I would begin. I inhaled my mixture of eucalyptus oil, camphor, and menthol and took from my pocket my little round pitch pipe.

Then I did it.

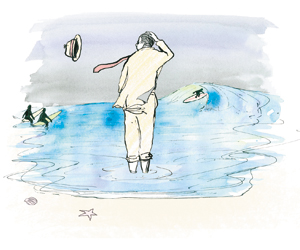

The article about the ’01 graduate who boxed, and was going pro, moved me. There was much of myself in it. I wanted to talk to him. Unwanted advice, unsolicited and, of course, unheeded would be met with a sneer and a rolling of eyes. Are you finished, old man? he would say.

I took a walk on the beach. It was a cold day, with a strong wind. The sea and the sky were both battleship gray. When they are son-age, you want to say something. You want to give a piece of yourself. But I am getting too old for any more rebuffs, for the barely courteous listening. I walked along the tidelands. I had to jump out of the way as the tide threatened to overtake me. With shoes and socks and long pants, I was not prepared for this.

When you turn pro, you will come against killing machines, maybe ten years your junior.

Tell me something I don’t know, he would say.

They will have been doing this since puberty.

Now are you done? his look would say.

Maybe in the vernacular I could at least be heard. Been there, done that. Don’t do it.

There would come a look almost of hatred.

A sudden incoming tide soaked my feet and pants. A strong wind blew my hat off, sending it cartwheeling down the beach.

I started to go after it. Then I stopped. I knew I would never catch it.