Original Source:

The world of Walden

By Elizabeth Station

Photography by Dan Dry

Many modern-day readers respond to Henry David Thoreau's Walden with quiet desperation. In his youth, English professor Eric Slauter was one of them. "It was a book I hadn't really liked in high school," he says. The tone is "incredibly snide and holier-than-thou."

So in 2008, when he was asked to talk to local high-school teachers about Walden, he focused more on the making of the book than its content. Slauter took his lead from "Economy," the chapter in which Thoreau lists every penny spent to build his house in the Massachusetts woods.

For his "Thoreauvian-style reading" of Walden, Slauter consulted publishers' records-the original publisher was Boston's Ticknor and Fields, later Houghton Mifflin-and found it cost 43 cents to make each copy, which sold for a dollar in 1854. Digging deeper, he discovered that a large, invisible cast of characters turned the rugged individualist's manuscript into a book. Slaves grew the cotton for early 19th-century paper pulp. Blacks and whites labored side by side at the Boston Stereotype Foundry, a worker-owned collective where Walden's printing plates were manufactured. New England women-who had recently entered the industrial workforce-toiled at paper mills, operated steam-powered printing presses, and sewed together pages.

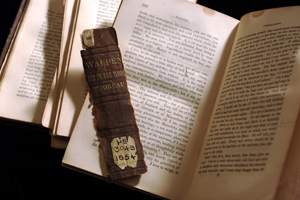

For his research, Slauter used a pair of Walden first editions in the Special Collections Research Center. One, which he and his students dubbed "good Walden," is in near-perfect condition. "Bad Walden," its well-used twin (above), is falling apart. That's fine with Slauter, who says, "I'm trying to take the book that everyone associates with solitude, manual labor, and the environment and put it back into the messy, gritty world in which it was produced."

Return to top