The end of African American literature

Literary scholar Kenneth Warren contends that the formal designation went out with Jim Crow.

By Laura Putre

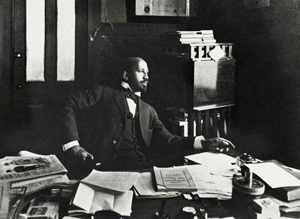

W. E. B. Du Bois pondered the fate of African American literature after Jim Crow. Photography courtesy New York Public Library.

In 1950 the editors of Phylon, which W. E. B. Du Bois had founded a decade earlier, asked prominent African American writers and literary critics to imagine a nation without Jim Crow segregation and consider what it might mean for black literature. Would that designation crumble if African Americans, no longer deprived of a political voice, had less need for art to highlight injustices and portray their struggle? Or would the distinctiveness of black culture persist when segregation was no longer the law of the land?

Kenneth Warren, the Fairfax M. Cone distinguished service professor in English, came upon the obscure special issue (called "The Negro in Literature: The Current Scene”) of the scholarly journal while researching his own questions about the viability of African American literature as distinct from American literature. Studying the Phylon special issue, he found that even before Jim Crow began to fall apart with the US Supreme Court’s ruling on Brown v. Board of Education, members of the black intelligentsia were not only looking ahead to a world without segregation but also considering such a world’s implications.

“Whatever they believed about the distinctiveness of black life or sensibility,” Warren says, many were hoping for the end of Jim Crow and aware that it would pose a challenge to African American writing.

Warren’s new book, What Was African American Literature? (Harvard University Press, 2011), brings the Phylon debate into the present. He argues that black literature as a critical grouping worked only during the historical period when “separate but equal” was constitutionally sanctioned. During that time, literature by black writers emerged from a set of imposed limitations that forced African Americans to live as outsiders in mainstream America. It was consistently forward thinking, looking ahead to the end of segregation. When Jim Crow ended, so did black writers’ persistent view toward the future. Conversely, contemporary literature that attempts to portray a universal black experience, such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved, is past based, looking to historical struggles to illuminate the present.

Once legal segregation ended in the 1960s with a series of court decisions and federal legislation, social inequality did not end, of course. But the shared boundaries of black life that made for a distinct literary grouping did, Warren argues. “There are no longer the conditions under which it makes sense to say, as it did, say, in 1940 when Richard Wright publishes Native Son, that this is somehow representative of the black condition,” he says.

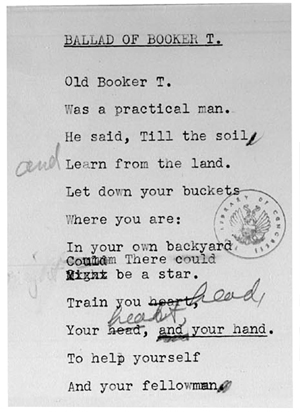

A manuscript copy of Langston Hughes’s “Ballad of Booker T.” Document courtesy Library of Congress.

The author of two previous books of literary criticism, So Black and Blue: Ralph Ellison and the Occasion of Criticism and Black and White Strangers: Race and American Literary Realism (both University of Chicago Press), Warren initially presented a slimmer version of What Was African American Literature? in 2007 as part of the W. E. B. Du Bois lecture series at Harvard University. A member of the Committee on African and African American Studies, Warren specializes in the Harlem Renaissance and 19th- and 20th-century American and African American literature.

During the lecture series, he detected discomfort in the audience as listeners wrestled with the idea that if African American literature ended around 1970, then black writers working today are no longer producing African American literature. That discomfort, he surmises, stems from a hesitancy to acknowledge that the end of Jim Crow was a significant milestone. The hesitancy is a response to past experience with conservatives who use the ideas of progress and color-blindness to proclaim that current inequalities are rooted in individual responsibility rather than ongoing social problems.

“I understand that fear,” Warren says, but “insisting the system of racial discrimination and racial inequality has continued unbroken despite the end of segregation actually doesn’t enable you to get at the causes of contemporary inequality.”

Warren ultimately added a conclusion to the book that brings the contemporary literary scene more fully into his argument. He closely examines Michael Thomas’s 2007 novel Man Gone Down, which follows an African American protagonist’s personal journey toward financial solvency. Although the character struggles with his identity as a black man trying to make it in upper-middle-class society, Warren contends that his ordeal is more of a post-9/11 condition (the protagonist is resolving inner turmoil after a friend died in the World Trade Center attacks) than representative of a singular black experience.

“However much a writer now wants his or her work to be representative in that way, we are no longer historically at a moment where that is possible,” says Warren. “Man Gone Down is a very good novel—I really enjoyed engaging with it—but it would be a mistake, I think, to call it a representative novel from the standpoint of black American literature.”

Although their predecessors “felt they had to demonstrate in one way or another that black people were indeed capable of producing good and serious literature,” contemporary African American writers are no longer part of an “anomalous undertaking,” says Warren. “You’re not going to have to argue, yes, indeed, blacks are producing literature.”

Updated March 28, 2011

Return to top