The University of Chicago Magazine

October 1997

Being Simon isn't simple

Rock back and forth, like this. Not so fast. A little slower, slower. That's it. Now, when Bruce puts his hand on your shoulder, pull away. Show him you don't like that. Don't let him comfort you."

On a muggy August morning in an abandoned South Side printing plant furnished to resemble a house in Pilsen, psychiatrist Bennett Leventhal, who has spent most of his life helping autistic children become more nearly normal, is teaching a nearly normal child how to appear autistic.

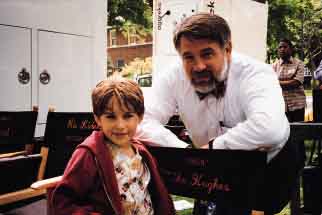

Luckily, the child is a quick study. He's Miko Hughes, 11, working on Mercury Rising, his ninth feature film, in which he plays Simon, a central character. The movie is a suspense thriller about car chases and puzzles, wicked people in federal agencies, and lots of money changing hands. Bruce Willis plays the good guy, Art Jeffries, a rogue FBI agent who is desperately trying to protect Simon after the boy's parents are murdered by the bad guys.

The plot revolves around Simon, a lonely little boy lost in his own world, afraid to let anyone else in. His talent is puzzles. He's good at them, so good that he has solved one too many, broken a code that the ne'er-do-wells use to communicate, and that means he must be eradicated.

What better way to create tension: a helpless, innocent child who can't comprehend, often doesn't even notice the dangers that swirl around him. The only problem was that "none of the script writers, nobody on the set, no one involved had the foggiest idea of what an autistic kid is like," recalls Miko's dad. "You just can't learn all that from a book."

So the filmmakers enlisted Leventhal, chair of psychiatry at the University and a nationally recognized specialist in autism research and treatment. "He created Simon's character from the ground up," says acting coach Denise Woods, a teacher at Juilliard. "Autism is so vast. Simon's character could have gone anywhere, but Bennett came in and gave us an outline, made him consistent, taught us how he would talk, how he would behave. " That meant rewriting dialogue, modifying Simon's vocabulary, and choreographing his movements.

None of this was simple. Autism is a neurobiological disorder that dramatically affects a child's social and language skills. Some children with milder forms do well in school, build friendships, and eventually hold good jobs. Others can't connect and require life-long parental or institutional care.

"We had to choose a set of common behaviors that made sense for a reasonably high-functioning autistic child," says Leventhal, "but that were also consistent with the needs of the story." So Simon speaks, occasionally-in simple, stilted sentences-and has very limited social skills. He never makes eye contact. And he has several tics and quirks, stereotyped repetitive movements such as constant rocking and a fondness for pushing buttons.

In early May, six weeks before shooting started, Miko, his parents, and Woods moved to Chicago to begin working with Leventhal. They studied videos of autistic children. They practiced appropriate motions and developed a walk, a speech style, and a repertoire of sounds. They even visited schools where Leventhal consults and met children with the disorder.

Child actor Miko Hughes and Dr. Bennett Leventhal confer on the set.

Rather than train a gaggle of child actors for a scene in a classroom of autistic children, Leventhal persuaded director Harold Becker (City Hall, The Onion Field, Taps) to recruit children from the Keshet Day School in Northbrook. "The scene came much easier-once we got the kids in place-than it would have with professional actors," says Woods. "All the kids knew Bennett. He helped them feel at home on the set. And they paid little attention to the cameras."

That scene also confirmed Miko's training. When the producers looked at the first cuts and tried to pick out the one non-autistic child in the scene, they couldn't.

Leventhal, too, has learned much. "This has made for an educational summer," admits the psychiatrist, who has put in many long days, nights, and weekends on the set, spending much of that time on the phone or handling paper work for his "day" job. "I've learned a lot about the movie business, which actually shares a lot of the stresses and challenges, the frenzy and the tedium, of the modern health system. But I've also discovered some things about my own profession, how doctors and the public think about the details of a disorder, what's essential and what isn't. I hope this movie might change the way some viewers think about this complex disease, might make them a little more understanding or compassionate."

His participation might also encourage a few more people to go see the movie when it opens next spring. According to Miko, a stringent critic of substandard work: "If it weren't for Bennett, this movie would suck."-J. E.

Also: