|

|

|||||||||

|

Glimpses

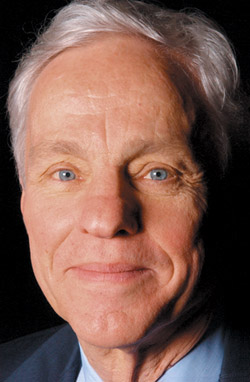

Richard Atkinson, PhB’48, winner of the 2003 Alumni Medal—the highest honor given by the University’s alumni association—has the perpetual tan of a longtime Californian. He also has the open gaze of a straightforward thinker. His career in higher education has included time as a Stanford psychology professor researching memory, cognition, and learning; as the National Science Foundation director who engineered the first exchange between U.S. scholars and scientists and their counterparts in the People’s Republic of China; as chancellor of the University of California, San Diego; and as president of the University of California, where in 2001 he sparked a nationwide debate by calling for a test that assessed high-school students’ learning in specific subjects rather than ill-defined notions of aptitude. How the native Chicagoan found his way to the College: A friend and I had arranged to spend Saturday playing basketball. When I arrived at his home his mother greeted me at the front door and explained that he had to cancel out on our plans since arrangements had been made for him to take the College- entrance examination at the University of Chicago. I was very disappointed, but then my friend called out from a second-story window—much to his mother’s displeasure—that I should go with him to the University and that we would be back in time to salvage the rest of the day. I had nothing better to do and agreed. We arrived at Cobb Hall. The person in charge had my friend sign in for the examination and then turned to me and asked for my name. “Oh, no,” I said, “I’m not on your list and I’m not here to take the exam.” He said, “Well since you’re here, you might as well take the exam.” So I did. A few weeks later my friend received a letter of rejection and I was admitted. His professors: I took Observation, Interpretation, and Integration in a special section taught jointly by President Hutchins and Mortimer Adler. Hutchins was at the peak of his fame, and Adler had played a key role in developing the Great Books program (he was affectionately referred to as “The Great Bookie” by students). We had about a dozen students in the class, and the discussions were intense. Even to this day I consider myself something of an expert on Plato’s Republic. I took Biological Sciences from Anton Carlson, one of the world’s great scientists, who was an equally brilliant teacher. His textbook with Johnson, The Machinery of the Human Body, is a classic. My introductory chemistry course was taught by Harold Urey, a Nobel laureate, who later became a lifelong friend. For approximately a year, I roomed in the home of Professor David Riesman, who was famous at the time, but later became even more famous when he wrote The Lonely Crowd. He often invited me to parties at his home that included some of the great social scientists of the era. And for some time I worked as a research assistant for Professor Nicholas Rashevsky, who was involved in formulating mathematical theories of biological and social processes. I did endless computations for him on equations that were basic to his theories. This predated digital computers and the work was done on a hand-cranked calculator. We ran into real problems that we never quite solved because the equations proved to be too disorderly. Years later they were to become part of what is now called chaos theory. The roots of SAT reform: In the 1940s there was an interesting debate among academics about the nature of college entrance examinations. The principal focal points of this debate were at Harvard University and the University of Chicago. To oversimplify matters, President James Bryant Conant of Harvard University and his colleagues advocated for a test designed to measure aptitude, whereas the Chicago contingent argued for a test designed to measure achievement. Conant’s perspective won the day, and with it came the SAT. Conant later in life expressed regrets about his role in promoting the SAT, but it was too late. With the changes that go into effect in the fall of 2006, the SAT will be reinvented in the form that the Chicago group advocated many years ago.

|

|

Contact

|